Interviews

A Poet’s Sage Words – An Interview with Marilyn Chin

Marilyn Chin is an award-winning poet and author. Born in Hong Kong and raised in Portland, Oregon, her works have become Asian American classics and are taught in classrooms internationally. Marilyn Chin’s books of poems include A Portrait of the Self as Nation; Hard Love Province; Rhapsody in Plain Yellow; Dwarf Bamboo, and The Phoenix Gone, The Terrace Empty. She also published a book of magical fiction called REVENGE OF THE MOONCAKE VIXEN. In addition to writing poetry and fiction, she has translated poems by the modern Chinese poet Ai Qing and co-translated poems by the Japanese poet Gozo Yoshimasu.

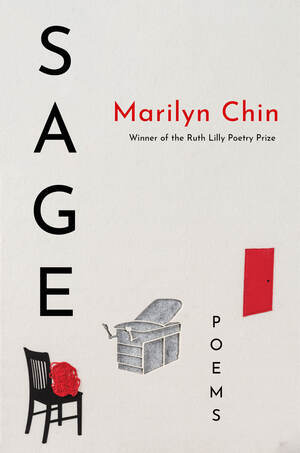

In her newest book, Sage, Chin writes with a fierce vulnerability. Sharing her deeply personal yet relatable experience during the pandemic, Sage is a window to the intense musings of a longtime activist poet that never rests. Both sage and succulent, Marilyn is a poet that holds your hand while she spins you at 100mph. Sage leaves you dazed and breathless, a profound feeling that stays with you, long after you’ve finished reading.

This interview was conducted by Thi Nguyen on October 15, 2022. Thi Nguyen, a California Native, is currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing, focusing on poetry, at the University of New Orleans.

Thi Nguyen: Sage is so timely as it reveals the range of emotions you felt during the pandemic: loneliness, anger, frustration (sexual and mental), gratitude, and hope. How did your experience during the pandemic impact your writing process? Also, how does Sage differ from your previous collections?

Marilyn Chin: The pandemic is the major demon character in this book. I am an autobiographical poet (somewhat), and my feelings and peregrinations are in my work. During the pandemic, I felt very lonely, cut off from my usual trips to Asia and to many of my friends. My teaching turned remote! I missed doing live readings and interacting with the audience. This book is also filled with “commissioned” works, where subject matter and celebrations, remembrances, etc. were predestined by some other powers. I also turned up the satire and humor; I needed to entertain myself through this dark time. The book is a variety show; each poem does its own personal dance. Hopefully, the whole spectacle is greater than the sum of the parts.

Thi Nguyen: I think because

you had such a wide range of varied parts, the sum is the spectacle. Even the title, Sage has various meanings. Sage is defined as either a wise person or the plant that is burned to promote healing and wisdom. And in the first section, which is also titled “Sage,” the poems depict sage as something desired and a gift. What does sage mean for the book, for this section, and the intended audience?

Marilyn Chin: Ha ha, I am both a wise person and a plant, probably a succulent. Kinda pale green, gooey inside, and sturdy. Wild sage and rosemary grow lavishly all over my yard in San Diego. They have been there for over 20 years! They thrive despite my neglect.

My sage advice in this section is meant to be light-footed, witty, humorous, sometimes dyspeptic, or outrageous. I wrote the sequence with specific addressees or beloveds in mind. Various pieces are teasing Maxine Hong Kingston; a birthday poem for Toi Derricotte, and various poems to students and demonic exes. A memorial and prayer for my friend David Wong Louie; A gratitude sequence for my friend M.O. I wanna write poems that are meaningful to me and my neighborhood. And perhaps, the world could listen in and show appreciation!

Thi Nguyen: I identify as Asian American, and your poems are meaningful to me, especially as your poems bring attention to the current social injustices against Asian Americans. You do this in the poems “You Go, Me Stay, Two Autumns,” “If,” and especially “Coda: 2022." And yet “Coda: 2022,” also recognizes poetry’s limitation with this line: “A poem can’t change destiny It’s impotent lux." You’ve defined yourself as an activist poet, a paradox that leans into this very tension, and yet you keep writing, why?

Marilyn Chin: During the pandemic, I helped deliver hot food to various elderly aunties. They spoke about their fears regarding catching Covid and about being the target of random violence. One lady in a wheelchair told me she was robbed in front of Walmart.

I, myself, heard slurs during the pandemic. A deranged person yelled: “Go back to China” and lunged toward me with drug-fueled rage. I saw pure hate in his eyes. Once again, the Asian community is being scapegoated. We did not steal your railroad jobs at Rock Springs. We did not invent the virus; I have always battled racism and sexism in my poems; now, damn it all, I also must battle ageism. The activist poet can’t get any rest!

Thi Nguyen: And you haven’t! You’ve been a working poet for over three decades, with your first collection of poems, Dwarf Bamboo,

published in 1981. In Sage, especially in the section “Folksongs Revisited,” you blend the then and now. What are the folk songs you’re referring to, and what goal is accomplished by revisiting them?

Marilyn Chin: I am a poetry nerd! I’ve spent my life investigating various forms and styles from the multiple sides of my literary inheritance. Folksongs go way back in human history: from anonymous western ballads to the Chinese classic Shijing, to Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and Odetta, to Narcocorridoes, and border ballads about Mexican drug cartels (my students made me a fascinating and dirty mixtape). Folk songs express the suffering and joys and the aspirations of the people. They can be devout and raunchy; sublime and ridiculous. They are personal and political. I love to write about villainous lovers, mean grandmothers, and wild teenagers. I have said that the self represents more than the self; it represents the stories of the nation. My contemporaries probably dismiss folk songs as being old-fashioned. I purposefully write outside of the prevailing winds and am inspired by a vast variety of genres. In this book, Sage, I wanted to resurrect the folk song.

Thi Nguyen: Speaking about “the self-representing the stories of the nation,” a lot of your poems in Sage deal with loneliness during the pandemic, especially the poems in the section titled “Shadowless Shadow.” You offer dark lines, such as, “we shall die alone," and “I have no father, no mother / No nation, no god / No lover in my cold bed / No one to bury me when I’m dead." But then you also offer lines of love and hope, such as “Look up / your future is bright” and “We must turn to / Love." How do you reconcile the self and the nation and respond with hope despite all the injustices you see in the world? Where does that love come from?

Marilyn Chin: Oh, I’m a poet who thrives on tonal dissonance and could wax and wane from despair to wild bursts of rage and love in a single poem. I go where the poem wants to go. And let the magic happen. At first, the poem might address a killer who murdered innocent women in Atlanta; or an invisible threat that is omnipresent in the poet’s mind, or an abusive father. How wonderful, that in a flip of a switch, the poem can make a turn of phrase, and magically change tone and perspective, and veer toward illumination and forgiveness. As Auden says, “Poetry makes nothing happen.” But I always believe that a good poem can illuminate, if not articulate, what’s really happening in this world.

Thi Nguyen: I loved how you ended Sage with a detailed play-by-play of your night using Auntie Wu’s birthday gift to you, a traditional Chinese ink brush painting kit. Within the painting process, you arrive at some poignant epiphanies:

• Fuck you who hate identity poems, U R nobody! I am nobody too! Everybody’s somebody to somebody! You aint nobody till somebody lover you!”

• “The strokes are irrevocable. Once the ink is laid, there is no revising it”

• “Mei Ling, it is never too late to change the world”

Can you comment on how you wrote out this reflection, and why you included it as the end to Sage?

Marilyn Chin: I do not journal or own a diary. I’m too lazy to document my life in real time. I often think about my auntie who bought me a cheap Chinese calligraphy set when I was six years old. I emigrated from Hong Kong to the U.S. at 7 and never saw that auntie again. But once in a while, I would dream of her. I mourn her as I mourn my own mother. Wu 无 is the negative particle. It’s an anti-word. It means Naught. I remember a calligraphy class in Hong Kong where my teacher hit my knuckles for holding the brush wrong. I still hold my pen in an awkward manner today, remembering the sting. In a Chinese painting class, Professor Cheng at University of Massachusetts, Amherst, often sighed at my clumsy mess. I remember being obsessed and staying up late playing with ink and brush, painting rocks that look like mounts of dog poo. Disastrously hilarious! But I loved every minute of it! Professor Cheng retired to Taiwan, and I followed him there on a Fulbright fellowship a decade later, continuing my mean brushwork. The brush is emblematic of my struggle and joys in the process of making art. At midlife, I still approach each new page with “beginner’s mind,” filled with childish shenanigans and foolish dreams.

Thi Nguyen: You mentioned Professor Cheng along your creative path, and I am reminded of the dedication: “for the teachers.” Who are the teachers that have inspired you, and how have they pushed your career in a meaningful direction?

Marilyn Chin: Gosh, all my past teachers from grade school, high school, college, the Iowa workshop; all of the great and not so great poets I’ve read in the past have contributed to my imagination. I was lucky enough to receive tutelage from a variety of teachers: Ai, Denise Levertov, Donald Justice, Adrienne Rich, June Jordan, Daniel Weissbort, and Hualing Nieh, just to name a few. Then, there are all the Classical Chinese professors as well.

Thi Nguyen: You are also a teacher. What is the most important thing your students should know or understand about you and poetry?

Marilyn Chin: I can’t say that I am an inspired teacher, myself, competing with the likes of Jesus, Buddha, and Sidney Poitier in “To Sir with Love.” The invisible Ms. Othmar uttering “wawas” in the Peanuts cartoon, now she’s the true sage!

For many years, I fretted about teaching poetry workshops. I know I can’t really teach anyone how to become a great poet. They must suffer and play in their own way through the process. There’s that old cliché—it’s a combination of talent, discipline, and luck that will keep a poet going. It also helps to have lived an interesting, messed-up life.

Presently I’m teaching intro to poetry writing to freshmen. And I am enjoying it. Mostly, I just make them read poems. You can’t grow an imagination if you don’t read.

This is what poets do: we read and write. We take out that rabbit brush and torture ourselves with long hours of making mistakes, and sometimes, and rarely, if we are lucky, we might write something memorable and wonderful!

SAGE (for my students)

by Marilyn Chin

The Sage is a kumquat in yoga pants

She will fight for your honor, or not

She’s rocking two layers of a pink Hazmat suit

And used stilettos from Saks

The Sage says

Your padre killed my madre’s madre

In a reptilian empire ruled by mommadres

Herstory is inexact

The Sage crouches, flashes double swords

Wipes out poverty, cures racism

Saves Baby Yoda from Moff Gideon

Sorry, my bad, the Sage cannot!

She enters the doorless door and breaks the knob

Reprinted with the permission of the poet from Sage (W. W. Norton, 2023).