Interviews

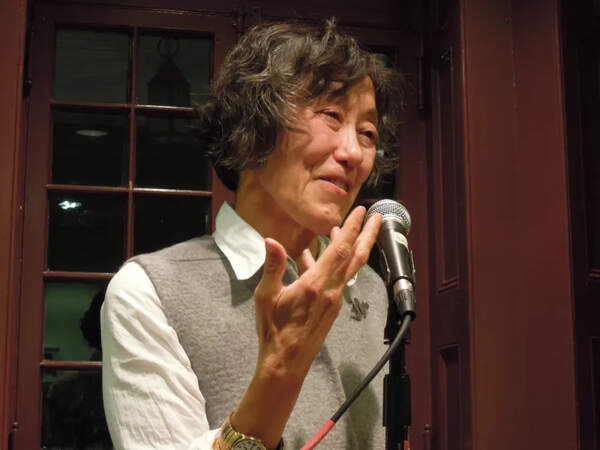

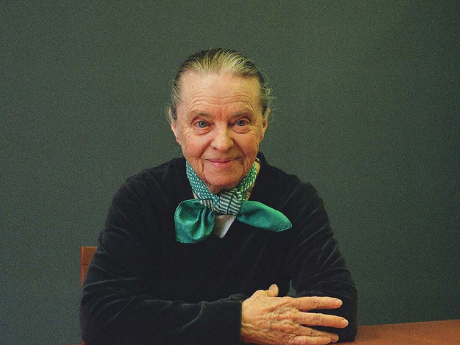

A Conversation: Marie Ponsot & L. B. Thompson

L.B. Thompson: What's the best thing about turning eighty?

Marie Ponsot: Oh practically everything! (Laughs) What can I say ... The combination of expectations being— not heightened or lowered, but evaporated: I don't really expect anything of myself, at all. (Laughs again) It's so liberating, you have no idea! I don't care! I really don't care! And that's partly of course because I have a lot of habits, which carry me. There are certain things I have learned in life that I like to do and so I go off and do them, and they're satisfying. That's about it. I'm very interested in what the day is going to present, but I'm not saying to myself, Oh boy, will I get this right? Can I manage this? Or, I hope I don't fuck up. I don't care.

LBT: Are your eighty years anything like what you would have forecasted for your future?

MP: Not at all. Not remotely resembling. Nothing like. I guess it depends on which set of expectations you pick: the expectations I had when I was fifteen or thirty or forty-five. You know they changed in some fairly radical ways. Up until I found myself pregnant I was quite sure I never wanted to have children. After the birth of my first child I felt that it was something that I really greatly enjoyed, something I was going to do again as soon as possible, and I did. That is, I think, kind of paradigmatic of what motivates me—something happens more or less accidentally, and I discover it, and I would have said if you had asked me ahead of time, "Well no, that's not really anything I could stand, or be interested in." I had W.C. Fields' attitude towards children, you know.

LBT: Which was?

MP: Well you just don't really want them around.

LBT: Until you find yourself with seven of them?

MP: Yes! And really for pleasure, you know, having a great time. And it took me probably another 45 years to realize that although I thought and could chat quite cheerfully with myself about the idea that I was doing this for pleasure because I really liked doing it—and that was true, deeply true—the fact is I was doing it because I was a member of the generation that produced the Baby Boomers. And everybody else my age was doing exactly the same thing. Did I know that at the time? No. Or perhaps I knew it, but I was certainly not conscious of it. That was just another occasion when I could tell myself, No matter how conscious you think you are, how carefully you think you're examining your life, you aren't.

LBT: Any other big surprises, other things that Marie at fifteen or thirty-five would not have imagined?

MP: At fifteen I thought I would never have to worry about money. At forty-five I worried about money. At eighty I don't think about it any more at all. ... When I needed money for my children's welfare that was nerve-wracking. Fortunately I discovered teaching. You can't make a royal living, but you can enjoy yourself. That was the period of my life when I wasn't publishing at all or even thinking about publishing because I couldn't, it was too hard for me to do. I could design the shoe, I could even be the factory, but I couldn't be the salesman. So, in my new selected poems, out of the piles of stuff written during that time, I picked one for each year from 1946 through 1971, and it was a lot of fun to do.

LBT: You were translating then, too, right?

MP: Yes, but the heavy translating years were the ten years before I started teaching. I started teaching at forty-five. I had always thought I'd hate to teach because everybody in my family was a teacher. My brother was a teacher, my mother was a teacher, my cousin Dorothea was a teacher, my great aunt Minnie was a teacher. How could I do that? They'd done it! And I really backed into it. And was very lucky to do so, because it was a great joy, is a great joy, and a lot of fun, and it has never been otherwise. What kind of a racket is it when you say to fifteen good writers, bring me in a new poem next week, and they do it! I mean, if you like poems, this is really the way to go!

LBT: Have there been surprise disappointments as well as pleasures?

MP: I don't know that disappointment is the right word, but I certainly have had some fairly large things go astray, or go inside-out and upside-down in my life. I married thinking that it would be permanent. That it was indissoluble. In reality —I think through simple and complicated misunderstandings—it turned out to be ephemeral. But it was less disappointing than astonishing. I couldn't believe that it was all going astray, but it was, it did. And it was lovely when it was over.

LBT: How has your translating from the French fed your poetry?

MP: I wonder about that sometimes... I did twelve years of Latin, and although I have lost my Latin vocabulary, the sense of English as having lots of Latin roots was very acute for me when I was in junior high school. I remember puzzling over that, thinking passion and patience and passive all have the same root. And that sense of the rootedness of words was the biggest effect that knowing anything about a foreign language has had on me.

My French is pretty deep in me somewhere so the French language itself has probably had less of a direct effect than my reading of French poetry. In the introduction to the Oxford Book of French Verse, there's a story about André Gide at Oxford, sitting next to A.E. Housman and being very apprehensive because he knew his English was not quite good enough and he greatly admired Housman's poetry, and he wasn't at all sure whether Housman spoke French. Finally, Housman turned to him and said, in perfectly modulated French, Tell me, Monsieur Gide, why is it that there is no French poetry? That's one of those great stunning statements of all time. There's a sense in which—although I could easily write a whole book disagreeing with him—I rather do agree with Housman. Reading a good deal of French poetry at various periods in my life has made me aware of the kinds of poetry in English that French does not offer, of what they have to make do without, of the difference of the currents.

LBT: Do you think that the fact that French philosophy has been so prominent has affected their poetry?

MP: No, I don't think so. I think the French would prefer that version! (Laughs) Yes, you know, We are the reasonable ones. And so reasonable a language is it that many of the things that Brenda Hillman does, for example, really squeak in French. You can't be a-grammatical, you have to be anti-syntactic, and you can't loosen the bounds and still hold on to anything in French.... The built-in urgency of the logical connections and appropriations is really something that you would long to get away from. So surrealism must have been a terrible temptation, they fell head-over-heels. For me the thing that is most wonderful about French poetry is the way that it deals with questions of being a somewhat stressed language. And it has called very strongly to my attention the fact that English is a somewhat stressed language also.

You can apply a metrical grid to a great deal of classical, canonical French poetry just as you can to English poetry, but in both cases the way in which people normally speak would not accord with that grid at all. The one thing the poet can do to determine stress in the line is the rhyme. That's a good reason for either using or dispensing with rhyme depending on whether you want that big beat, or not. In French poetry since Nerval and Rimbaud a little bit later, it's clear that they are substituting speech patterns for grid.

LBT: The Bird Catcher contains several poems in form; what draws you to established forms?

MP: The History of Literature! Ha ha! How about that! I'm interested in lyric poems. I have ways of imagining— probably all inaccurate, but all based on something that somebody with an authoritative attitude has taught me—the Origins of Language, the Origins of Poetry. I think poetry is one of the primitive forms of language. I like Suzanne Langer's idea that the original union of language is not, as poets sometimes think, with song, not with music at all, but with dance. It's a body rhythm, and that's what it's expressing and making memorable and attractive to remember and use again even if you forget the words. You remember the rhythm and use it again.

LBT: It puts it in the body...

MP: Yes.

LBT: How did your years teaching freshman writing courses at Queens College affect your thinking about language?

MP: In a hundred ways, I think. The big thing that it made me feel more certain of was that everybody can write poems. We never did in that class, especially since I was teaching by choice people who were the least able to write, who had not passed the assessment test into Freshman Comp. We didn't really have time to write poems, although I knew that they could. I could tell from the way that they wrote everything else that they knew the difference between kinds of language and uses of language. I was really confirmed by the excellence of their work, by the way they could—chiefly by being told that they could—progress to writing well, from not being able to compose anything at all. It's perfectly clear that if you just open the door and get out of their way, they can do it. And that makes me, as a writer, sort of ambitious. I really would like to write poems that different kinds of people would like to read. By "different" I mean people who don't ordinarily read poems. I would like to write poems that people who do read poems would like to read, but also poems that would be legible to people who don't.

LBT: Once you mentioned to me that you fall in love repeatedly, and that this is crucial. What makes you fall most often? What are the hooks that are likely to grab you?

MP: Often it's language, someone's ability to suddenly say something that stops me dead in my tracks. I think the human animal is extremely attractive (laughs) to other human animals. People are very beautiful in all their shapes and ages and everything. It's extraordinary. And I have to admit—at this point in my life I guess I can afford to admit it—many, many of my reactions and responses to things in life are not rational or even just directly sensual, but aesthetic. It's a dirty word, but that's what I find attractive, beauty. I really like it. I really like beautiful people and things.

LBT: What would you most like to do or see in your future?

MP: What would I most like... well, peace in the world! I don't really have any smaller wishes that can't be easily gratified. L.B. Thompson: What's the best thing about turning eighty?

Marie Ponsot: Oh practically everything! (Laughs) What can I say ... The combination of expectations being— not heightened or lowered, but evaporated: I don't really expect anything of myself, at all. (Laughs again) It's so liberating, you have no idea! I don't care! I really don't care! And that's partly of course because I have a lot of habits, which carry me. There are certain things I have learned in life that I like to do and so I go off and do them, and they're satisfying. That's about it. I'm very interested in what the day is going to present, but I'm not saying to myself, Oh boy, will I get this right? Can I manage this? Or, I hope I don't fuck up. I don't care.

LBT: Are your eighty years anything like what you would have forecasted for your future?

MP: Not at all. Not remotely resembling. Nothing like. I guess it depends on which set of expectations you pick: the expectations I had when I was fifteen or thirty or forty-five. You know they changed in some fairly radical ways. Up until I found myself pregnant I was quite sure I never wanted to have children. After the birth of my first child I felt that it was something that I really greatly enjoyed, something I was going to do again as soon as possible, and I did. That is, I think, kind of paradigmatic of what motivates me—something happens more or less accidentally, and I discover it, and I would have said if you had asked me ahead of time, "Well no, that's not really anything I could stand, or be interested in." I had W.C. Fields' attitude towards children, you know.

LBT: Which was?

MP: Well you just don't really want them around.

LBT: Until you find yourself with seven of them?

MP: Yes! And really for pleasure, you know, having a great time. And it took me probably another 45 years to realize that although I thought and could chat quite cheerfully with myself about the idea that I was doing this for pleasure because I really liked doing it—and that was true, deeply true—the fact is I was doing it because I was a member of the generation that produced the Baby Boomers. And everybody else my age was doing exactly the same thing. Did I know that at the time? No. Or perhaps I knew it, but I was certainly not conscious of it. That was just another occasion when I could tell myself, No matter how conscious you think you are, how carefully you think you're examining your life, you aren't.

LBT: Any other big surprises, other things that Marie at fifteen or thirty-five would not have imagined?

MP: At fifteen I thought I would never have to worry about money. At forty-five I worried about money. At eighty I don't think about it any more at all. ... When I needed money for my children's welfare that was nerve-wracking. Fortunately I discovered teaching. You can't make a royal living, but you can enjoy yourself. That was the period of my life when I wasn't publishing at all or even thinking about publishing because I couldn't, it was too hard for me to do. I could design the shoe, I could even be the factory, but I couldn't be the salesman. So, in my new selected poems, out of the piles of stuff written during that time, I picked one for each year from 1946 through 1971, and it was a lot of fun to do.

LBT: You were translating then, too, right?

MP: Yes, but the heavy translating years were the ten years before I started teaching. I started teaching at forty-five. I had always thought I'd hate to teach because everybody in my family was a teacher. My brother was a teacher, my mother was a teacher, my cousin Dorothea was a teacher, my great aunt Minnie was a teacher. How could I do that? They'd done it! And I really backed into it. And was very lucky to do so, because it was a great joy, is a great joy, and a lot of fun, and it has never been otherwise. What kind of a racket is it when you say to fifteen good writers, bring me in a new poem next week, and they do it! I mean, if you like poems, this is really the way to go!

LBT: Have there been surprise disappointments as well as pleasures?

MP: I don't know that disappointment is the right word, but I certainly have had some fairly large things go astray, or go inside-out and upside-down in my life. I married thinking that it would be permanent. That it was indissoluble. In reality —I think through simple and complicated misunderstandings—it turned out to be ephemeral. But it was less disappointing than astonishing. I couldn't believe that it was all going astray, but it was, it did. And it was lovely when it was over.

LBT: How has your translating from the French fed your poetry?

MP: I wonder about that sometimes... I did twelve years of Latin, and although I have lost my Latin vocabulary, the sense of English as having lots of Latin roots was very acute for me when I was in junior high school. I remember puzzling over that, thinking passion and patience and passive all have the same root. And that sense of the rootedness of words was the biggest effect that knowing anything about a foreign language has had on me.

My French is pretty deep in me somewhere so the French language itself has probably had less of a direct effect than my reading of French poetry. In the introduction to the Oxford Book of French Verse, there's a story about André Gide at Oxford, sitting next to A.E. Housman and being very apprehensive because he knew his English was not quite good enough and he greatly admired Housman's poetry, and he wasn't at all sure whether Housman spoke French. Finally, Housman turned to him and said, in perfectly modulated French, Tell me, Monsieur Gide, why is it that there is no French poetry? That's one of those great stunning statements of all time. There's a sense in which—although I could easily write a whole book disagreeing with him—I rather do agree with Housman. Reading a good deal of French poetry at various periods in my life has made me aware of the kinds of poetry in English that French does not offer, of what they have to make do without, of the difference of the currents.

LBT: Do you think that the fact that French philosophy has been so prominent has affected their poetry?

MP: No, I don't think so. I think the French would prefer that version! (Laughs) Yes, you know, We are the reasonable ones. And so reasonable a language is it that many of the things that Brenda Hillman does, for example, really squeak in French. You can't be a-grammatical, you have to be anti-syntactic, and you can't loosen the bounds and still hold on to anything in French.... The built-in urgency of the logical connections and appropriations is really something that you would long to get away from. So surrealism must have been a terrible temptation, they fell head-over-heels. For me the thing that is most wonderful about French poetry is the way that it deals with questions of being a somewhat stressed language. And it has called very strongly to my attention the fact that English is a somewhat stressed language also.

You can apply a metrical grid to a great deal of classical, canonical French poetry just as you can to English poetry, but in both cases the way in which people normally speak would not accord with that grid at all. The one thing the poet can do to determine stress in the line is the rhyme. That's a good reason for either using or dispensing with rhyme depending on whether you want that big beat, or not. In French poetry since Nerval and Rimbaud a little bit later, it's clear that they are substituting speech patterns for grid.

LBT: The Bird Catcher contains several poems in form; what draws you to established forms?

MP: The History of Literature! Ha ha! How about that! I'm interested in lyric poems. I have ways of imagining— probably all inaccurate, but all based on something that somebody with an authoritative attitude has taught me—the Origins of Language, the Origins of Poetry. I think poetry is one of the primitive forms of language. I like Suzanne Langer's idea that the original union of language is not, as poets sometimes think, with song, not with music at all, but with dance. It's a body rhythm, and that's what it's expressing and making memorable and attractive to remember and use again even if you forget the words. You remember the rhythm and use it again.

LBT: It puts it in the body...

MP: Yes.

LBT: How did your years teaching freshman writing courses at Queens College affect your thinking about language?

MP: In a hundred ways, I think. The big thing that it made me feel more certain of was that everybody can write poems. We never did in that class, especially since I was teaching by choice people who were the least able to write, who had not passed the assessment test into Freshman Comp. We didn't really have time to write poems, although I knew that they could. I could tell from the way that they wrote everything else that they knew the difference between kinds of language and uses of language. I was really confirmed by the excellence of their work, by the way they could—chiefly by being told that they could—progress to writing well, from not being able to compose anything at all. It's perfectly clear that if you just open the door and get out of their way, they can do it. And that makes me, as a writer, sort of ambitious. I really would like to write poems that different kinds of people would like to read. By "different" I mean people who don't ordinarily read poems. I would like to write poems that people who do read poems would like to read, but also poems that would be legible to people who don't.

LBT: Once you mentioned to me that you fall in love repeatedly, and that this is crucial. What makes you fall most often? What are the hooks that are likely to grab you?

MP: Often it's language, someone's ability to suddenly say something that stops me dead in my tracks. I think the human animal is extremely attractive (laughs) to other human animals. People are very beautiful in all their shapes and ages and everything. It's extraordinary. And I have to admit—at this point in my life I guess I can afford to admit it—many, many of my reactions and responses to things in life are not rational or even just directly sensual, but aesthetic. It's a dirty word, but that's what I find attractive, beauty. I really like it. I really like beautiful people and things.

LBT: What would you most like to do or see in your future?

MP: What would I most like... well, peace in the world! I don't really have any smaller wishes that can't be easily gratified.

Originally published in Crossroads, Spring 2002.