Interviews

Questions of Faith: Richard Wilbur

"Questions of Faith" is a selection of excerpts from interviews that Dianne Bilyak has conducted over the past decade. The interviews began as her master's thesis for The Institute of Sacred Music & Arts at Yale Divinity School. The poets were queried about their religious upbringing, current practices, and how these may or may not have influenced their writing, as well as general questions related to faith, doubt, and meaning, and more specific questions related to each poet's work.

* * *

Dianne Bilyak: The first question I've asked every poet is: I have no preconceived notions of what God might mean for you or for anyone, would you talk briefly about the role organized religion played for you growing up, and what role it plays now, and how it might relate to the process of writing?

Richard Wilbur: Well, I was brought up as a member of the Episcopal Church, and I attended Sunday school and church with fair regularity. We lived about seven miles from Montclair, New Jersey, where there was a very good Episcopal Church of which my mother was particularly fond. And we got there when we could. One frequent pleasant obstacle was Sunday morning tennis. I have the game of tennis all mixed up with religion. In those days it was played with great formality, and you said things like "Ready, partner? Ready?" and so on. And I can remember that on the estate where we lived, people sat in a pagoda to watch the tennis, and often there was a prayer book lying on the table next to the tennis racquets. Like most teenagers, I strayed away from any kind of regular attendance at church when I was in high school and college, and then in time came back to it. And my wife, who was brought up as a Congregationalist, converted to the Episcopal Church and we were in it for the rest of our lives. I still have some habits from those old days. I say my prayers at night; I have a prayer book, the old one, next to my bedside. I love the language of it and I love many of its sentiments. And in our family we always say grace before meals—a lot of those pleasant habits of church-going persist with us.

DB: Have competitive feelings ever led to mistrust or envy? Did your writing and religious life help you to make amends with those facets of yourself?

RW: Well, I can understand envy and competitiveness, and I think I sometimes pose as less competitive than I am—that's something that has to do with early training on the tennis court. I saw in a bookstore the other day a very thick volume of Robert Lowell's letters, and I did what anyone in my position would do, I picked it up, looked in the index to see where he might refer to me. And there was one letter, I forget to whom, in which he was saying kind things about me. He kept saying I was a good man, but he also said a sentence that really pained me, he said, "We were almost good friends." And he explained that by saying my competitiveness was so strong that he felt it as a kind of searing presence when we were together. I was very sad to hear that. He himself was an extremely competitive person, and I hope that he projected some of that onto me, but I think this is a matter in which it's hard to speak for oneself. I know that I don't sit around the way Lowell and Roethke used to do and rank my contemporaries from 1 to 10. And yet, I know that there's inevitably a lot of ego in it. One thing I know about this is that, for most of my life, I've not been assignable to any school of writing; therefore I wasn't in any way part of a team playing against other teams. The person I was most aware of wishing to please, the person I most wanted approval from, was Robert Frost, and it would have been a little silly for me to think, as I began to write poetry, that I was competing with him. I simply wanted his good opinion. That is the most strenuous feeling I ever had about placing myself in the world of poetry.

DB: I've read that faith is the opposite of certainty. Denise Levertov, from her poem "Opening Words," has these lines: "I believe with/doubt. I doubt and/interrupt my doubt with belief." How might resistance be a form of belief, or doubt?

RW: Well it seems to me that if one takes the propositions of any religion seriously, there's going to be doubt in the experience, there's going to be intermittency and one is going, as D.H. Lawrence once said, "to be converted over and over." And I remember Mr. Eliot, T.S. Eliot, saying that doubt is inseparable from the experience of faith. It's something we shouldn't be ashamed of, and it's funny because, if I may digress, Eliot is also the person who said that fancy thing about how the spirit killeth but the letter giveth life. I guess he was objecting to a sort of hazy spirituality one finds sometimes with some people. But he seems there to be saying that you'd better believe every word in the creed, and he thus represents both ends of the doubt and belief pattern, he's saying wouldn't it be nice, really, to believe that whole marvelous Nicene concoction that we say in church, and at the same time he's saying that any energetic religious life involves doubt.

DB: In almost every interview that I've read, the interviewer challenges the fact that you write in form or blank verse. And you say that it develops just as organically as a free verse poem.

RW: That's right.

DB: But at this point, it seems that people think that writing blank verse is an act of radical subversion, would you expand on that a little?

RW: Well, it has a great deal to do, in my individual case, with whence came the idea of writing poetry in the first place. It's poems that made me want to write poems in the first place. And although I've always enjoyed a good deal of free verse poetry, starting with Whitman, most of the poems which give me a feeling that something has been rightly said make use of some form or other, for the sake not just of form but of emphasis and music and the indication of the stages of an argument. So I think that when I began to write it just seemed natural to me to work on poems in ad hoc formal ways. I would never, ever have said to myself, now I must write a sonnet. But if you've read enough sonnets, it will happen one day that you find yourself writing one because the logic of what you have to say will draw you to writing in eight lines and six lines. You can emphasize the steps of the argument with one or another sonnet rhyme scheme. I don't write sonnets on the whole—I think I have two or three of them and one or two translations—but any form that has seemed to you successful in someone else is likely to come to you, as if by accident, in the process of finding words for what's developing within you.

DB: In 1966, you wrote an essay called, "On My Own Work," and you had two questions that concluded the piece. You asked, "Is it possible, for example, to speak intelligibly of angels in the modern world?" and "Will the psyche of the modern reader consent to be called a soul?" And I'm wondering, after saying that however many years ago, if you have any sense that that's true, or not true?

RW: I think that a word like "soul" is dangerous, and it's likely to sound pious to a degree that will alienate the reader, and make it hard to follow the rest of what is being said. So when I use such a word, I try to use it in such a way as to govern the way it will be taken. And I don't want to throttle the reader and say, this is a religious poem and that's what soul means. In the long poem, "The Mind Reader" the mind reader echoes the prayer for purity that precedes the communion. I thought that it might interest you to notice that because, in a way, that long poem is a necessarily failed attempt to imagine the mind of God. And that echo of the liturgy is meant to indicate as much to the reader.

DB: You've sometimes talked about how writing poetry can be lonely and I'm curious if your move to the theater felt akin to a search for a more congregational experience.

RW: I'm drawn to plays and am fascinated by the production of them, and I like, for the sake of my own poems, the training in emotive expression that translating French plays can give you. I certainly do have a feeling that, when I write for the theater, I want to see it on the stage, and I want audiences to respond to it. And so there's something congregational about that. I'm sure that's some part of the attraction toward the theater. I also like to go around—I can't do it much anymore—and read my poems to audiences. It seems to me that the poems haven't been fully published until I've spoken them aloud to people.

* * *

Richard Wilbur is the author of numerous collections of poetry including New and Collected Poems (1988), which won the Pulitzer Prie, and Things of This World (1956), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He has published numerous translations, children's books and collections of prose. He has received the Frost Medal, the Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, two Bollingen Prizes, the National Arts Club medal of honor for literature, two PEN translation awards, and is a former Poet Laureate of the United States.

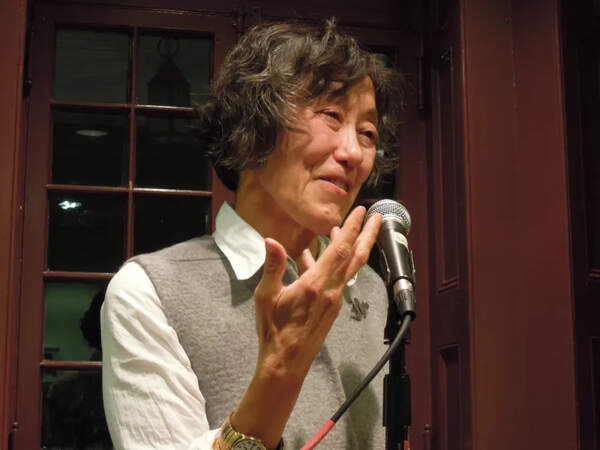

Dianne Bilyak has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and her first book of poems, Against the Turning, will be released in September 2011. Through the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale Divinity School, she received a graduate degree in religion and literature. She has been interviewing poets for several years and editing the transcripts for inclusion in a manuscript called Poetic Faith. Please visit her website.