Interviews

Questions of Faith: Richard Blanco

"Questions of Faith" is a selection of excerpts from interviews that Dianne Bilyak has conducted over the past decade. The interviews began as her master's thesis for The Institute of Sacred Music and at Yale Divinity School. The poets were queried about their religious upbringing, current practices, and how these may or may not have influenced their writing, as well as general questions related to faith, doubt, and meaning, and more specific questions related to each poet's work.

* * *

Dianne Bilyak: What role did organized religion play for you growing up?

Richard Blanco: I grew up in a very traditional, Latino Catholic family. I went to Catholic school from kindergarten through high school. Despite this, we were not "strict" Catholics. We went to church on Sundays, etc, but our faith was more of a backdrop to our family life than a focal point.

Dianne Bilyak: What role does it play now?

Richard Blanco: I view my Catholic upbringing as simply a part of my cultural makeup. I recognize that I am Catholic in a cultural sense, but I have not been a practicing Catholic since my early college days.

Dianne Bilyak: Are there ways that a particular religion (or lack thereof) has influenced your writing process or what you write?

Richard Blanco: I make reference in my writing to many of the Afro-Cuban deities and superstitions that migrated into Catholicism in the Caribbean from the West African religious practices of Yoruba. This resulted in a more fatalistic and mythological "brand" of Catholicism that holds a blurrier line between the living and the dead, between the "here" and the "after." This spiritual stance I think is reflected in many of my characters. Other than that, I would say that it is the "lack" of organized religion that has influenced me indirectly. Having never adhered to any particular dogma (though I have explored many), I eventually reached for the essence of the divine within myself. I try to always write from that center of the self that is connected to the divine, free of the fears and arrogance of the ego.

Dianne Bilyak: It seems that writing allows me to build a structure outside myself in order to see parts of myself that were previously unavailable. Are there ways in which that is a similar experience for you?

Richard Blanco: Poetry is smarter than we are. Or the poem is smarter than the author and so I relate to what you are saying in the sense of creating a space. It's almost like it gives you what or who you want to be or who you really are. It's like standing in front of a mirror. At first it's a little foggy, but eventually it clears. So one of the reasons I try to create a space is to understand myself in this world—to understand the big questions: myself, my family, what we are doing here, why this in particular, what are human beings made of—those kinds of questions. On many levels, even though I'm talking about cultural issues, I'm really examining the human condition (whether it be triumph, suffering, hope, etc). So, poetry for me creates this alternate reality. Sometimes others read my stuff and say, "Your poetry is fictionalized of course, but you've verbatim re-written family histories." It's in attempt to create a truer truth, in a sense. And I couldn't imagine not doing that. I think I would go insane. It's the real me. The rest is kind of like a façade, like going through the motions. Poetry makes me stop and look at those things. It definitely creates space for me.

Dianne Bilyak: Li-Young Li has said, "Silence is to poetry as space is to architecture." In what ways do you find space for spiritual contemplation or literary contemplation and what parts of your life offer you opportunities for this?

Richard Blanco: The whole idea of silence, of language is overwhelming sometimes. Elizabeth Bishop says something like: it's not about what's said but about what's not said. And I find that often when I go throughout my day, doing this and doing that, thinking about this, thinking about that, or even working on a poem I'm revising, I just stop to look at a pine tree. And in that microsecond, everything becomes clear. And that's the right brain, maybe. Or that's God. But it's that crystal clear moment when everything comes into silence. I feel like a lot of poets want to overwork poems, and I'm guilty of that, certainly. And some of the best poems and most well received poems are known for—you know that old cliché—what's between the lines. When I read a poem by Elizabeth Bishop it can seem so simple, quiet, and silent, and yet what's happening between those lines is so incredible you can't even put words to it. And so I find that I try to remember that space whenever I write. I think what it's about is getting rid of the ego, and the fear and sense of grandeur that comes with the ego.

* * *

Richard Blanco is the author of City of a Hundred Fires, which received the prestigious Agnes Starrett Poetry Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press; Directions to The Beach of the Dead, which won the 2006 PEN / American Beyond Margins Award; and most recently Looking for The Gulf Motel. He was the inaugural poet for President Obama's second inauguration.

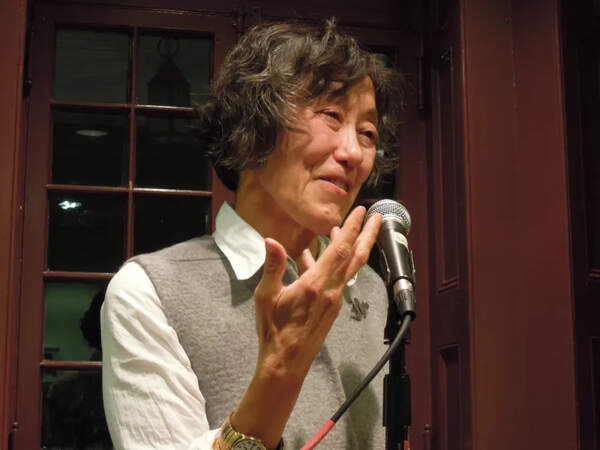

Dianne Bilyak is the author of Against the Turning. Through the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale Divinity School she received a graduate degree in religion and literature. She has been interviewing poets for several years and editing the transcripts for inclusion in a manuscript called Poetic Faith. In 2012 her play, Cradle to Gravy,was selected to be part of the United Solo Theater Festival in Manhattan. Please visit her website.