New American Poets

New American Poets: Tim Z. Hernandez

Mama's Boy

They say I'm a mama's boy

like it's a bad thing, when all along

I thought that's what a man was.

They say my skin was made from goat's milk

& dandelions

and that my eyes were plucked

from cherry blossoms in the month of February.

A mama's boy they say,

with hands too soft for picking

legs thin as sprigs of mesquite.

They say my voice lacks

the asphalt grit of courage, that I

should work on it

and that my name is too short

to call me by name,

and they're right—

When they say

I was born with a hole in my heart

the size of a tiny fish eye.

They're right when they shout, Mama's boy

and poke at the tenderness that is my back

claiming that my hair was quilted from a beggar's scarf

and that my smile was strewn

from tender husks of sugar cane

it's true—

Since I've fondled and groped at the inside

of my mama's womb,

just a squirming confirmation of father's lust,

I've scheming ways to retreat

to that warm familiar sack of membrane

and love manifold.

This is why

I lead with the docile nose of a house cat,

speak my intentions

in raw doggerel utterances

from the stiff

core of a loose

taciturn tongue—

Why I tweeze the nose hair clean

behind locked doors,

using the reflection off surgical steel

buck-knives

& limp

toilet handles,

lather my jaw with baking powder and lava rock,

skin tax

for the morning peel

because I am soft

—zephyr soft

and teeming with secrets.

I am the watermark of houses submerged,

my whimpering howl a rivulet of what remains

from the hidden

tidal tears of men,

which is why they do not lie when they say

my feeble knees are the silken steel

edges of grandfather's worn plow discs

tease that my stomach is a sofa cushion

stuffed with the down of a thousand geese

and that my nipples

are the fragile embroidery

of Victorian gowns.

My words, they say, these boyish longings

do not pounce from the gut like

alloy drum fire

candy wine lingo

do not come on like

razor neck nicks

splashed in allspice fire

will not crowbar the ribcage

or shoehorn the chunk boot

or adorn the rearview in

deer hoof rabbit

knuckle luck charms

Instead, they are made

from sugar water & pomegranate

lust, jelly for the dawn song

warm rhythms

for the doubtful eye

& the accusing heart—

And because of this

they jab their crooked fingers in my face

and shout, Mama's boy!

like it's a bad thing

when all along, you see,

I thought that's what a man was.

Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Introduction to the work of Tim Z. Hernandez

Major Jackson

What is most prominent in Tim Hernandez's poetry is how he gorgeously underscores the entwined relationship between the journeys of everyday people, especially the farmworker communities of the San Joaquin Valley, and the land in which they live, love, die, and breathe. His poetry does more than dignify lives; it elevates their joys and sufferings to the artful realm of enchantment, and yet, there is nothing pretentious or hollow about his poems. With an intimate appetite for the fantastical, his tone switches between the reverent and awe-inspired to the comedic and whimsical. I count him as one of the best emergent poets writing today.

Statement

Tim Z. Hernandez

Growing up I wasn't one of those well-read literary types, not in high school, and not in those liminal years after, when I found myself in a void, a space of total possibility. I was not well read at all, but well read-to. My first encounters with literature were through voice, expression, and embodiment. It was my mother, Lydia Hernandez, a self-made woman and product of the harsh New Mexico landscapes, who believed in the transformative magic of language and narrative. And she would read to me during those long migrant road trips, field to field, across state lines and shifting landscapes. The whole way my father, Felix Hernandez, a sarcastic Tejano, spun these tales, these written words, off in new and strange directions. He was a consummate jokester, a stand-up comedian of the fields, and of family barbecues. But always, stories were at the heart of our family. This was my beginning.

Though I am a poet now, I did not/ do not think of writing in those terms. I only tinkered with poetry because it was the most accessible to me. It was immediate. A pencil. Paper. A few words. And I had something. And then one day, very early on, someone pointed at me and called me a poet. And I stood a little straighter because of it. My ears perked up because of it. My eyes widened to the experiences before me. That person was the poet, Juan Felipe Herrera. I camped out on his front door in Fresno. His wife, the Zen performance artist and poet, Margarita Luna Robles, invited me in and cooked me a breakfast of eggs with a fresh salsa. I never left. I slept on the couch with Rocko, the family dog, who would wake me each morning by licking my face clean of sleep. I had never seen so many books in one house before. I pocketed them, stuffed them in my socks, and still checked others out that I'd never return. They were well aware of my tranzas—my poetic swindling. They called it hunger. Accessibility. This word is key for me.

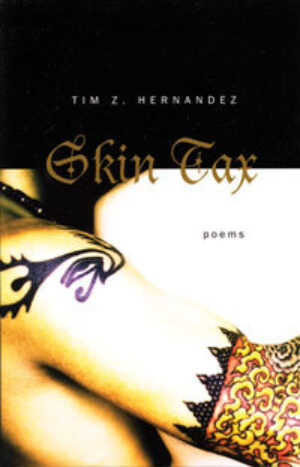

Later I studied poetry, then fiction and theater. I also pursued my visual arts tendencies and apprenticed with Bay Area master muralist Juana Alicia. In the end, the objective is not poetry for me, but connection, plain and simple. A word, an image, music, shadows, detritus—all of this is game. This is how my collection of poems, Skin Tax, was conceived. Words that sprang from bonfire conversations, anecdotes of intimacy, raw speak, macho ballads, ball games, scars, urgency.