Old School

On George Herbert

Love (III)

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lacked anything.

A guest, I answered, "worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth, Lord; but I have marred them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

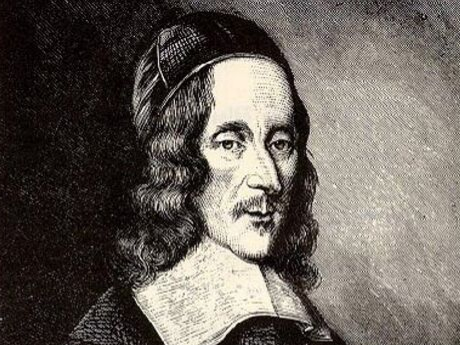

Isaak Walton's The Life of Mr George Herbert opens by telling us, "George Herbert was born the third day of April, in the year of our redemption 1593." But the priest-poet had few readers until three centuries after that date. During his lifetime he never published a book, and it is only because Herbert placed the manuscript of The Temple in the hands of a friend that we know of his poems at all. This was Nicholas Ferrar, the leader of the Anglican religious community at Little Gidding, (commemorated in the last and most ecstatic of Eliot's The Four Quartets). Herbert's few early readers included Crashaw, Vaughan, and Traherne, poets who acknowledged him by the sincere compliment of imitation. The number of his admirers began to grow about one hundred years ago, and it's accurate to say that Herbert is more valued at present than at any time before. If Donne was the key figure for the modernism embodied in T.S. Eliot's poetry (and his followers') during the first part of the twentieth century, it seems clear that he has yielded his place to Herbert as a model for contemporary poetry written in Britain and the United States. Do we know why? Eliot himself of course admired Herbert and praised him for honesty:

All poetry is difficult, almost impossible to write: and one of the great permanent causes of error in writing poetry is the difficulty of distinguishing between what one really feels and what one would like to feel.... verse which represents good intentions is worthless—on that plane, indeed, a betrayal. The greater the elevation, the finer becomes the difference between sincerity and insincerity, between the reality and the unattained aspiration. And in this George Herbert seems to me to be as secure, as habitually sure, as any poet who has written in English.

Several decades later, W.H. Auden put his own reactions to Donne and Herbert in characteristically pungent terms: "Great as he is, I find Donne an insufferable prima donna; give me George Herbert every time."

It was because of Elizabeth Bishop's warm partisanship for Herbert that I first read him closely—and immediately saw she was right to single out in him the qualities of speechly directness and simple, even "homely" diction. Her own poems' way of working through a problem, looking at it from all sides, no doubt drew lessons from self-questioning masterpieces of Herbert's like "Affliction I" and "The Collar."

One of our most distinguished contemporary critics has written a very perceptive book about Herbert—I mean of course Helen Vendler's The Poetry of George Herbert, to which these comments are indebted. In it she argues that the reader need not be Christian to appreciate Herbert, in fact, she quotes Housman to the effect that "good religious poetry...is likely to be most justly appreciated... by the undevout." Whatever the truth of that assertion, the fact remains that admirers of Herbert certainly include non-Christians who have sufficient reasons for valuing his poems. Anthony Hecht, for example, chose Herbert as the author he wished to present in the Ecco Press series of "essential poets." In his introduction to that volume, Hecht focuses on Herbert's technical ingenuity, the profusion of nonce forms the poet invented and brilliantly deployed. He also marvels over the surprising fusion of wit and piety in Herbert. After all, Herbert was a Cambridge laureate, and he knew the conventions of courtly love poetry well enough to adapt them to devotional subjects with no effect of incompatibility. His biography, of course, includes experience on a high social stratum as well as a lowly, pastoral one. How a young nobleman liked and admired by James I lost his hopes at court and became the rector of the obscure parish of Bemerton in Wiltshire is a story I recommend reading to anyone unfamiliar with it.

In any case, Herbert was able to make use of some aspects of early experience that maturity taught him to rate at its true value—that is, he saw the literary interest of courtly discourse but acknowledged it as less than the supreme gift of divine love. It was a resolution not arrived at easily. C.S. Lewis, in a well-known book, cautioned his readers against "mere Christianity," a thoughtless reflex acquired during childhood and never seriously questioned thereafter. Herbert's religious faith was not that kind. It had had to stand several tests, beginning with the more rational deism of his elder brother Edward and his own real attraction to a life devoted to pleasure and the pursuit of ornamental learning. When we read his prose treatise A Priest to the Temple, sometimes called The Country Parson, we can discover in his description of parish duties traces of the jolts this cultivated and courteous young man must have suffered when suddenly plunged into daily dealings with plain-speaking people far from the centers of learning and refined behavior. Yet they are traces only, and the overriding impression of the book is one of stable conviction that a priest will either replace pride with humility or will not manage to be priest, that is, a servant of God in the task appointed. The account of his striving to become such a servant, though, is embodied most passionately in the poems. Again and again they unsettle us by the fierceness of the struggle recorded and the terms under which Herbert conceived it.

One of Herbert's short poems in Latin treats the subject of Jesus' garments, taken and divided among the Roman centurions after they had executed him, leaving him with nothing to bequeath to his friends. A translation of it reads, "If, Christ, while you were were in agony, your garments were inherited by your enemies and not by your friends as custom would command, what then will you bequeath to them? Yourself." Using an analogy that Herbert would certainly comprehend, we can say that he has bequeathed himself to us in the form of consummately achieved poems.

I reread Herbert often, returning to two poems in particular: "Affliction [I]" and "Love." One of Herbert's earmarks is his preference for single-word titles, sometimes preceded by the definite article "the" as in "The Sacrifice." The single-word title doesn't tell much and therefore acts to draw in its readers, who want to know how the topic will be treated. Using just one word is rather blunt, and when the title is "Affliction," the powerful implication of suffering acts like a gavel calling the court to order so that serious business can be conducted. The suffering dealt with in this poem is multiple, and Herbert the plaintiff brings up sources of his pain one by one, presenting them to a deity inseparable from the qualities of goodness and mercy. On the face of it, making an inventory of complaints to be presented to God doesn't strike us as a pious action. No, but it does seem honest, freeing the poem from the charges of hypocrisy and sanctimony that are often leveled at devotional verse. It isn't possible to think that Herbert is inventing his discomforts. On one level they make him look self-pitying, lacking in the fortitude expected of an ordained person. Experience teaches, though, that all people at least inwardly complain, some few of these managing to avoid direct expression of their sufferings. Stoicism is admirable in daily life, but the poet's job is to show us how feelings, even negative ones, can find expression in words and formal means of expression that are in themselves solacing.

"Affliction [I]" uses a six-line stanza with the rhyme scheme ababcc, a fairly common format, with the difference that Herbert's is heterometric: Lines one, three, five and six are composed in pentameter; lines two and four, in trimeter. The rhythmic effect of the first four lines of each stanza is akin to the spring the ballad stanza puts in our steps. This rhythmic lift-off is followed by the solid, anchoring pentameter couplet, a dance-like rhythm yielding to something more grounded, if more pedestrian. You could say that rhythmic movement is recapitualted at the conceptual level by the unfolding "argument" of the poem. The first four stanzas present the agreeable part of Herbert's story. He considers his priestly profession and likes what he sees. "My days were strawed with flow'rs and happiness," he reports. And then affliction begins. First he suffers bodily illness and pain. Then his friends die, with the result that he loses the gift of mirth and the keen edge of wit. Brought up to take his place among worldly fellow-noblemen, he is thrust into the lonely profession of priesthood, and that in an isolated rural parish. Once put in place, he suffers further illnesses, which hamper him from doing the work entrusted to him.

In his present condition he says a startling thing: "I read, and sigh, and wish I were a tree;/For sure then I should grow/To fruit or shade: at least some bird would trust/Her household to me, and I should be just." Poems have often been figured through the metaphor of trees, the most significant variety being the bay or laurel tree, whose leaves were incorporated into the crown conferred on the winner of Greek poetic competitions. In this figure the bird nesting in his branches corresponds to the source of inspiration, an ornithological muse, maybe. The species of bird might even be a dove, associated in Scripture with the Holy Spirit. When Herbert concludes, "I should be just," he suggests that he would, once a true poet, feel his life was justified. Being a hindered priest does not suffice. He must also be a poet.

And yet as far along as the last stanza, he feels unresolved, tempted to abandon his calling and his God, saying, "Well, I will change the service and go seek/Some other master out." Then, in a split second, feeling the enormity of this betrayal, he concludes, "Ah my dear God though I am clean forgot,/Let me not love thee, if I love thee not." The last line is a paradox, composed with the wit we expect in Metaphysical poets. But what does it mean? This, I think: "Yes, I do feel love for you, God. But thus far that love isn't wholehearted; it's not a love so compelling and satisfying that I cheerfully accept the burdens you have sent me. And if I can't feel that kind of love for you, then please release me from feeling even this qualified emotion that I feel now. Divided consciousness is tearing me apart. Let me love you totally, or not at all."

It is an anguishing cry of the heart and not often equaled in devotional poetry. In a later poem, the one titled "Love Unknown" Herbert imagines a dreamlike (not to say surreal) scenario in which he goes to visit a personage designated simply as "a Lord." The poet brings with him a bowl of fruit at the center of which is his own heart. The Lord tells a servant to take it and throw it in a font, where it is plunged in a grisly bath of blood, saying, "Your heart was foul, I fear." The allegation is accepted, along with a request for pardon. But the pardon granted proves not to be enough: the poet goes for a walk one evening and comes upon a huge cauldron labeled AFFLICTION. He decides it requires a sacrifice and goes to his flock to fetch it. Returning, he says his "heart did tender it," at which point, the person in charge refuses the animal, taking the poet's heart instead and throwing it into the cauldron. He hears the words, "Your heart was hard, I fear." He doesn't deny the charge, but after being parboiled returns home and climbs into bed to recover strength. Alas, there he is afflicted by thoughts that he terms "thorns." Whereupon he hears the phrase, "Your heart was dull, I fear." The servant tells the poet that he has a greater and kinder Master than he knows. These three torments had a purpose. The font renewed what was old. The cauldron made what had grown hard supple; and the thorns quickened what had grown dull. Strong medicine, painful to undergo, and yet effective. The servant concludes:

Wherefore be cheered, and praise him to the full

Each day, each hour, each moment of the week,

Who fain would have you be, new, tender, quick.

The torments Herbert describes are understood as a means to foster qualities we associate with a person actively faithful. "New, tender, quick": these adjectives also describe a certain kind of poet, one who takes a fresh perspective, differing from the standard view of human affairs; one who has empathy for the sufferings of others; one who is alert, sensitive, and agile. "Love Unkonwn" is a good poem to recall at those moments when we feel afflicted by various misfortunes. We may complain about them, but put in the right perspective they can be understood as contributing to our humanity. And if we are poets, as adding a wider and more perceptive scope to what we write. If divine love was before unknown to us, the mystery of suffering shows us that it is a power who wants us to be more than we previously were. This knowledge leads to praise, sometimes composed in lines of poetry.