In Their Own Words

Angelo Nikolopoulos’ “Rear Stable: Auditions”

Rear Stable: Auditions

When I saw mine for the first time

in the tilted view of a compact mirror

I felt cheated, bored almost, having expected

something cavernous, something more alive,

but finding it taut, instead, like the stretched

rubber of a racquet ball. It was its lifelessness

that bothered me, how it adhered there, as inert

as a postcard, and I wondered how could it be

this that he loved most, why he spoke of it

so affectionately. Show me daddy's sweet asshole,

he'd say. Perhaps he knew better, being older,

having met me in my bathing shorts that summer,

my body thin and undeveloped, the younger

of two boys. Perhaps he saw possibility—

examining my parts like the bulk of a cedar,

his hands over bark, a sticky droop of sap.

I'd rivet my torso over his enormous knee,

grip the solid stalk of his calves, and let his fingers

work into me, until I became something else:

a stained letter box, the smooth curved handle

of a shovel. With linseed oil and pain

and delight littered in pools around our feet

he would make a thoroughbred out of me.

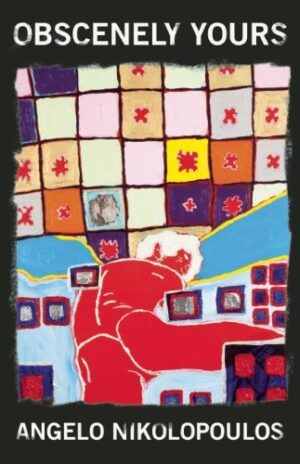

From Obscenely Yours (Alice James Books, 2013). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author

On "Rear Stable: Auditions"

Like Auden, I believe a poem should be more interesting than anything that might be said about it.

Now that that's out of the way, what's there to say about Rear Stable: Auditions? Perhaps that I wanted to write a poem about things that thrill and baffle me: sex and love and beauty. All that hearty good stuff that goes into the Enchantment bouillabaisse. I'm not a pioneer here, obviously. Some people say sex is inherently political. Pat Benatar says love is a battlefield. And John Keats says a thing of beauty is a joy forever.

Who am I to disagree?

Learning the pleasures of the body—its shades and capabilities—is an exquisitely physical enterprise, of course, but all the more I'm compelled to think of enchantment in linguistic terms.

My poem asks, more or less, what's the asshole? We have some words for it: Hershey Highway, keister, the heinie. And then there's balloon knot, corn hole, and wrinkle star—your lovely ham flower.

But what does it mean to us, indwelled as we all are in our bodies?

Perhaps it signals shame and filth, perhaps pleasure and delight? Perhaps we defer to language in the end, the words we choose to name it? After all, isn't one's old dirt road another's gleaming starfish?

At 15 I admit mine wasn't much: a featureless, lifeless thing. Why should I know any better?

But then language comes along and accomplishes its nifty trick, assigning significance and charge where there was none. I wanted the lover in the poem, as all lovers must do, to provide contour, that horizontal line from which the self differentiates itself. Like language itself, he provides meaning through contrast and context. I am younger, I am inexperienced, the self says. I am becoming something else.

Don't we become something else in the lover's eyes?

And later, doesn't it become something else entirely when we write about it? We can't replicate experience through language, we know this, so what are we doing when we write from memory, about experience? Document. Witness. These don't seem quite right. Reportage is never enough for the artist. I call it an audition, like many of the poems in my book Obscenely Yours, in order to suggest tentativeness, a provisional footing. The poem doesn't document but refashions experience, through language, into something entirely autonomous, otherworldly. We imbue events and encounters—some scant, tawdry details—with significance and meaning and wonder by the mere fact that we narrow our attention to them, by naming them. Isn't, then, the poem an exaltation?

It's naughty, I know, to talk about the ass, but why should the lowly—the seemingly base—be exempt from our attention, when they provide such coordinates for discovery, when they offer enchantment?

Yeats says that love has pitched his mansion in the place of excrement. And I wanted to write a poem about that mansion, high up there where the sun don't shine. That backdoor and prison purse. My rear stable. Whatever you call it.