In Their Own Words

Erica Wright on “Lola and the Apocalypse”

Lola and the Apocalypse

She sees catastrophe in every crow,

in every knocked-down clothesline—mostly

volcanoes and floods but sometimes scourges,

blue tongues, waves that forget their place

and storm into cities. Her mind stops at flesh peeling

back from the bone until it's white as milk,

the kind that makes grown men grow breasts,

and they feel that this is a catastrophe, but it's not.

Once when men were automobiles, the roads were slick

with sweat. They gleamed. Days were lost

to spectatorship, making bets on which color would rise up

out of the dark. Our girl made twenty dollars

on violet, but someone stole it. Who knows who?

It was hard to tell one chrome from another.

You couldn't cross for fear of getting hit, a parade

of reds and browns. And maybe the afterlife is a bookshop,

and she's been good, so she'll get to loiter

by Pop Culture/Crime instead of Business/Money.

From her perch, she'll count personality types. The schizotypals

will never object when she fondles their frontal lobes,

that gray, dirty satin. Elbow-deep in it. Her epigraph will remain

unwritten because there's no one left to scrawl platitudes:

For every pain, there is a duck with your name on it.

But there aren't any ducks. At ponds worldwide, they ate

each other when no guests tossed crumbs and shooed away

the geese that strike as if their bodies are lit fuses.

When cities were coal mines, the children played

color games, too, but it was hard to determine a winner.

Lola knew a man there who didn't balk at anything, could stare down

whatever slime-bellied beast approached their home.

She can't recall his name, but it could have been Roger.

They had books, too, mostly Cultural Studies.

"Maybe I'm not alone," she thinks. "Maybe the devil stalks me

right this minute, wants me to run, make it more exciting."

Lola sits down on the nearest ledge. "Ha," she thinks. "Haha."

She doesn't notice the fissure at first. It sneaks

between floorboards, and when she pries them apart,

her fingertips bleed in protest. They drip

onto the bleach-white worms that catch fire in the light.

And then the floor collapses and then the world.

The survivors are called hostages or will be

if any are met. Hostages in pines, hostages in barns,

hostages in the great wide open

that makes them feel slit, wrist to armpit, in littleness.

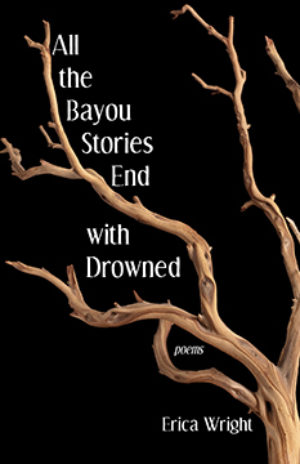

From All the Bayou Stories End with Drowned (Black Lawrence Press, 2017). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Lola and the Apocalypse"

You may remember the rapture of 2011. Sure, the threat of apocalypse comes and goes, but this one made national news. Harold Camper predicted that on May 21st, believers would be taken to heaven, and those left behind would face a cornucopia of horrors. Proselytizers took to their local channels with predictions and pleas. My friends and I quipped about not paying our student loans.

I was raised on the Book of Revelations, so I have a pretty clear picture of what the world ending should look like. Blood moons and earthquakes. A sea beast and a lake of fire. As a child, I believed that if we weren't physically in a church on that fateful day, we would be forgotten. That fear warred with my impatience on Sunday mornings, especially in the fall when all I wanted to do was explore the neighbor's old barn and pretend to find winged (not pale) horses.

On May 21st, I had a flight booked, which seemed useful. Not exactly holy, but maybe my plane's proximity to heaven would increase my chances of being chosen. Poet and translator Ricardo Maldonado called to say that if I were raptured, he would take care of my cat Lola. That's true friendship, right? I mean, companies like Eternal Earth-Bound Pets were charging more than $100 for the same service. I thought his generosity deserved a poem, so I started "Lola and the Apocalypse" as a hybrid joke-gift. I quickly realized, though, that what started as a silly premise allowed me to explore a theme that obsessed me—the lengths we go for survival.

In my other life, I write crime fiction, and you can only read or watch so many mysteries before you become something of an amateur expert on all the ways that we can die. Bullets, poisons, knives, ropes. Cars, trains, boats. Air conditioners tumbling from windows or water freezing on your front steps. I once read about a woman who woke up in a coffin at her own funeral, then died of a heart attack from the shock. Earlier this summer, my second cousin was bitten by a Mojave rattlesnake while saving his wife's dog and spent more than a week recovering in a hospital. Thankfully, he lived.

Ricardo and I used to play a game on the subway late at night called "Cheeses and Diseases." We would name as many cheese as we could, then as many diseases, each taking a turn until we couldn't think of another example. As far as I recall, we always reached our destination before running out of options. All of which is to say, humans are phenomenally fragile. I sometimes wonder how any of us make it through a single day.

And yet, we mush on. It's remarkable really, and "Lola and the Apocalypse" became a portrait of a woman trapped in the worst possible circumstances—perhaps the only human still alive—who approaches her situation with defiance rather than fear.