In Their Own Words

Jessica Baran's “On Dissonance”

On Dissonance (an excerpt)

12.

A plain, unvarnished impression leaves a burning sensation – a serious inflammation that actually burns a hole through the apparatus. Punctum. This is the language of explication: a collection of occasional terms. Humidity so dense it forms a cottony mantel; a striated rash erupting in air. It's a blemish on distance, an improbable affliction on perspective.

13.

Expressions of condolence empty into a paper cake box and fill it with the nothingness they are. To hand that box to its intended recipient is to hand them something much lighter than it should be. It's not the right surprise, unless you're allergic to sugar or dairy, and even then you'd expect something else instead. Expressions of sympathy vary only slightly from condolences as they require a similar but different sized box. More like the kind of box long-stemmed roses arrive in: long and narrow, suggesting elegance over exuberance. Which is right for the occasion? Black balloons, black streamers – it's hateful, you know it; it's all grotesque. What kind of personal feeling led you to believe this was right? Shhhh. Do you hear it? Shhhh, again. It's a rabbit. It runs across the night.

17.

An era the scale of a day. A pocket-sized wooden yard stick. Looking back doesn't always look long. These are the local impossibilities – flattening thought into pavement, recording the viscous tactility of wetness as it amasses on a lens.

20.

The sky means less when it infers a message. Either way: living with symbols is no surrogate. It's an unspecified reference. Like a photograph, which loses itself in its lack of evidence. It tells you repeatedly the wrong time.

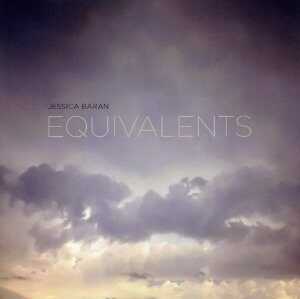

From Equivalents (Lost Roads, 2012). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "On Dissonance"

"On Dissonance" is a sequence of prose poems from the second section of my second book, Equivalents, the title of which I borrowed from a series of photographs by Alfred Stieglitz. His Equivalents—all several hundred of them shot between 1922 and 1935—are wallet-sized, black-and-white silver gelatin prints of the sky that are now considered the first abstract photography. On a short trip to Kansas City two summers ago, I saw a few of them in person for the first time in the Nelson Atkins' collection, and they appeared tiny and metallic. Not at all aloof and celestial–and never blue. Their quasi-industrial way of cordoning-off and composing nothingness made sense to me: they turned toss-away pieces of the daily continuum into conceptual stakeholders, and roughed-up (i.e. rendered dissonant) my usual assumptions about documentation.

When I discovered these photos, I was amidst a collaborative project with artists Gina Alvarez and Amy Thompson called 366 Skies, in which Gina took a photograph of the sky and I wrote a prose poem every day of the 2012 leap year (Amy, at year's end, designed and hand-printed the project as a massive series of letterpress broadsides). Half-revelatory and half-maddening, the insistent nature of this project aggressively shook out a lot of my personal stock-pile of bullshit and forced me to reassess who I was, in language and reality, on a calendar-day scale. What do I actually have to say? Call me a masochist, but I guess I was looking for this kind of experience. It was an opportunity to point a bare bulb at all the seemingly un-poetical stuff that made up my life and rigorously interrogate it. Having spent the past few years writing about contemporary art, I enjoyed connecting Stieglitz to this conventionally-deemed lower tradition of dailiness. It felt like a mild political act, and not a little un-antagonistic toward certain cultural and economic hierarchies. As the notion of perception was also such a driving conceit behind the project, the poems all suddenly became of a piece. Equivalents. This never fails to blow my mind when it happens.