In Their Own Words

Derek Mong “To Assemble This Poem Properly”

To Assemble This Poem Properly

begin from above. The first line wrote itself

in eraser. Your entrance refills with its cloud.

Can you feel now a dull tug on your pant leg?

You have shadows within shadows.

The poem strips them off like spare parachutes.

Watch their dark mouths briefly glisten

like guardrail reflectors. Leave silence

between them like warm loaves of bread.

Whatever small truth the poem hurtles toward

is already in your pockets. Release it here

and stop breathing. Watch it rain down

like disco ball light. If a story comes in, cold

from the margins, you alone can warm

its feet. To do so you must hold it

beneath the voice that trails you.

You offer the one it becomes on the ground.

The seamless transfer of two people

humming is one scenario in which the poem

successfully ends. In another these couplets empty

and you are a diver climbing their cool tubes

back up to the start. From there you see its finale

clearly, but do nothing to alter its course.

You'll soon crash through a tenth story window.

Do not worry. The poem's safe.

See its thousand shards glint at your feet.

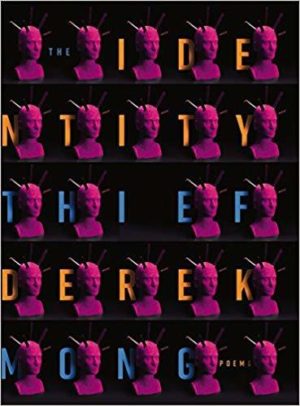

From The Identity Thief (Saturnalia, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted courtesy of the author.

On "To Assemble This Poem Properly"

Some poems are gifts; others are edicts. I knew a pilot once, a modern-day Hermes, who flew donated organs between hospitals. He was a young guy, a former student, and long after we lost touch I'd still picture him shuttling his biological cargo between the dead and the unwell. I worked his line of work into a poem ("We Live Our Lives through Other People's Bodies"); the poem's ending followed shortly thereafter—a gift. The title poem for my new book, The Identity Thief, required only modest coaxing. Its revisions were hard, but the voice was a gift.

In the poem printed above, "To Assemble This Poem Properly," another compositional logic prevailed: that of the edict. I had been trying at the time to strip my life from my poems, to prohibit the confessional, and see what shook out. If this edict fell short of T.S. Eliot's—"the progress of an artist is […] a continual extinction of personality"—it was, for me, a big deal. In my first collection, Other Romes, I gave a lot of airtime to the self. "To Assemble This Poem Properly" was among the first poems I wrote after that collection. Therefore the poem's second person, a you like police tape to keep the autobiographical at bay. Therefore the subject matter, other poems.

This too was an edict: write a poem about writing a poem; write it, but don't let it suck. Such poems usually falter on their own solipsism, self-regard, or low stakes. (Anyone who has ever workshopped knows what I mean.) If this one succeeds, it's only because I cheated my own prompt. This lyric is less about "assembling" (i.e. writing) a poem than about reading one. The "assembly" described doesn't happen on the factory floor so much as the family room couch. The poem explores the pleasure of readerly meaning-making. It reimagines the belief, made famous by Stanley Fish in "How to Recognize a Poem When You See One" (1980), that "critics do not construe a poem, they construct it." Ditto readers. Ditto the small child with her first book.

This is all to say that "To Assemble This Poems Properly" lacks a real origin story. I don't recall where I wrote it or when, but I do remember one of its influences: Donald Justice's "Poem," from Departures (1973). (Readers of that poem will recognize its tone here.) I remember it took work to finish it and more work to publish it. I remember it getting translated into Mandarin. I remember my mental memo: don't do x; try y for a change. This has become a go-to cure for self-imitation, though, like so much in my process, it takes time. Very few of my poems burst forward like solar flares or erupt with the regularity of geysers. Most push upward and outward like volcanoes. They shift like tectonic plates. One day there's a rumble and they're done.

If this precludes all but the occasional "eureka," it does allow me to revisit old work with new eyes. My pace is glacial; finished poems seem to move long after they're done. In rereading this one, I see better its attempt—via leaping, Deep Imagist images—to see reading as a gravitational force. The first couplet comments on poetry's staticky resistance. The third line reminds us that it takes just a tug to fall in. Reading is a drop zone that mixes danger, disrobing, and delight. Thus the shadows stripped "off like spare parachutes." Thus the mouths glistening "like guardrail reflectors." It's only in the pauses—linebreaks and the white space between stanzas—that solace (or silence) can nourish "like warm loaves of bread." Falling, I've learned, is one of my favorite conceits.

In "To Assemble This Poem Properly" falling leads to a truth that is, for better or worse, "already in [my] pockets": poems embody poets; reading joins poets and readers in an erotic, bodily act. "It is you talking just as much as myself," Walt Whitman tells us in "Song of Myself," for "I act as the tongue of you." For me, this is poetry's super power: it draws unlikely individuals together across space, race, nation, and time. Direct address accelerates (and accentuates) the process; it links two pairs of lips and lungs, two tongues and throats. The "transfer of two people / humming" approximates that short-lived union. It's a humble reimagining of a "barbaric yawp."

In the end, though, these comments are self-defeating. I've already acknowledged that this poem belongs to its readers. I am reminded that, in its last lines, it invites rereading, regardless of exegesis. I hope that it invites reassemble too, however its readers see fit.