In Their Own Words

Susan Wheeler's “The Maud Poems”

The Maud Poems (an excerpt)

Jeehosaphat

Good grief, you don't have the sense God gave geese. I told you this morning, I won't be your chauffeur. And take that ratty thing off.

Where the jays upset the feeder—

under the house where Jamaica hid—

hands in brook-water, cold—

Something wasn't quite Hoyle about the way she got that A. No, I don't like your just hanging out.

Oh, piffle. That's not what you said last night.

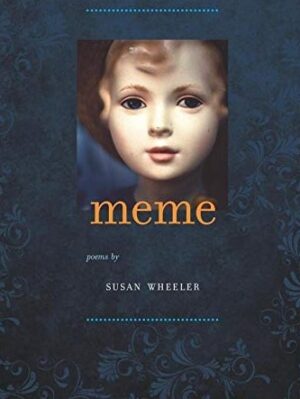

Poem reprinted from Meme (University of Iowa Press, 2012) with the permission of the author. All Rights Reserved.

On "The Maud Poems"

I began work on "The Maud Poems" several years before my mother died. I wasn't interested in autobiography but I was interested in my mother's particular vernacular and vocal imprint. She was an older mother for the time, she'd grown up in Topeka, Kansas, after the first world war; her father had left, her mother Olive ran a boarding house, and her uncle Meldrum owned a funeral parlor. Her idiom was one I heard bandied during the Watergate hearings, among senators of a certain age, and I was intrigued with using it to build a character based upon her within an extended poem. The character—the language through which it is imagined—needed a foil, and so the lyric intrusions came about organically.

It was not, however, a dispassionate enterprise. She was a formidable woman, someone who had become a designer and a teacher at Rhode Island School of Design, where my father ended up her student, and now she was failing. She wasn't the only mother without any affinity for mothering—she once said that as a child she couldn't get the point of dolls—and what a person was supposed to do to exorcise an, er, unhelpful mother's voice incorporated, embodied, in them had flummoxed me for years. So I wanted the two registers to get at the complex experience of a relief equal to grief, anger to allegiance.

I spent the last few weeks of her life with her. Each morning when I'd arrive at her hospital room, she was out cold, unrousable, and each day I'd think, that's it, until late afternoon, when she would suddenly wake, sit up, and begin to command anyone proximate. While she slept, my brother and I recalled her stock stories and expressions, and the "Maud" poems distilled from many pages of the notes that followed.

This elastic period seemed unstoppable. The last night I saw her awake I told her I had to tend to my class the next day, that my brother would be arriving, that I would see her the day after. I had just fed her applesauce, and was settling in to stay until she slept. She turned her face away and said, "Good-bye. Your work is more important than my death." I'm not ready to go, I began to say, but she repeated "Good-bye," and I realized I was being dismissed. Even now I'm not sure whether it was with bitterness or permission.