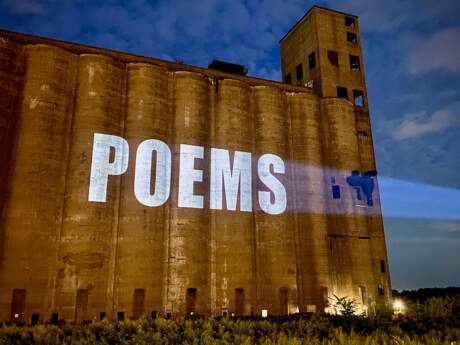

Pulitzer Centennial Poetry Celebration

Pulitzer Centennial Poetry Celebration

Thursday, Oct 27, 7:00pm / The Great Hall of the The Cooper Union

At this once-in-a-lifetime event, 13 Pulitzer Prize-winning poets will share the stage to read from their own prize-winning collections as well as select poems by past winners. Join us in celebration of their achievement, of the Centennial year of the Pulitzer Prizes, and of PSA's founding role in sponsoring the earliest years of the prize for poetry.

Featuring: Rae Armantrout, John Ashbery, Peter Balakian, Carl Dennis, Stephen Dunn, Jorie Graham, Yusef Komunyakaa, Sharon Olds, Gregory Pardlo, Philip Schultz, Vijay Seshadri, Natasha Trethewey, and Charles Wright.![]()

We asked all living winners of the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry to answer any two or more of the following questions. We will be updating this page as we hear from them, so be sure to check back!

Read answers from:

Rae Armantrout

Carl Dennis

Rita Dove

Robert Hass

Richard Howard

Ted Kooser

Lisel Mueller

Gregory Pardlo

Kay Ryan

Philip Schultz

Vijay Seshadri

Henry Taylor

RAE ARMANTROUT

2010 Winner, Versed (Wesleyan University Press)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

My mother, who had no particular interest in poetry herself, read me poems from a children's encyclopedia when I was very young. I remember especially liking "The Mad Gardener" by Lewis Carroll, which contains the wonderful lines: "He thought he saw a Banker's clerk/Descending from the bus./He looked again and saw it was/A Hippopotamus." That must be one of the best rhymes in all of literature. I think I remember the illustration which showed a purple hippo standing upright on a street in London.

I wrote my first poem in first grade. Our teacher, Miss Sampluski, had us all make up poems which she then bound into a little mimeographed book. My mother kept it. I came across it when she died and I was going through her stuff. It was nothing like Lewis Carroll. Somehow, I had taken to minimalism. It was about a little fish swimming "around and around and away."

What was the first poem you fell in love with? What was it that spoke to you?

The next poetry book I owned was Modern American Poetry, edited by Louis Untermeyer. My 7th grade teacher, Irene Douval, gave it to me. I've kept it, though, by now, it has some unsightly discolorations on the pages. Looking at the table of contents, I can see the poems she marked for me to read and the poems I marked as favorites myself (quite a different set). I remember being struck and amazed by Emily Dickinson's poem which begins, "A bird came down the walk:" (This is the way the punctuation and capitalization appeared in that anthology.). I was intrigued by Dickinson's tone. She liked this bird even as it was eating "the fellow raw." When I was twelve, this lack of sentimentality seemed transgressive, especially in a woman. And I was amazed by the way she described the bird's eyes as "frightened beads." It was unlike anything I'd ever heard—and still is, for that matter.

CARL DENNIS

2002 Winner, Practical Gods (Penguin)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

I began writing fitfully in high school, and in college, and in graduate school, but didn't decide that it was the kind of writing I wanted to give most attention to until I was twenty-eight, teaching in the English Department at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

I had just finished a poem that had given me a great deal of pleasure in writing, and thought I should try to see if I couldn't make that pleasure the center of my working life.

What was the first poem you fell in love with? What was it that spoke to you?

I can't remember the first poem I fell in love with, but I think among the earliest--when I was about thirteen--was this quatrain by one Sarah Norcliffe Cleghorn that I found in a school book:

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.

To me at the time this was a startlingly fresh reversal of expectation, with its working children and playing adults, that made a sharp political point for those in the know. I think I was taken especially with the fact that the speaker didn't sound angry or preachy, but merely reporting a quaint oddity, and that the reader was being asked to supply the right attitude the poet wasn't supplying, to share an unspoken insight with the writer. I was flattered by the thought that I could enter the club of the knowing. Well, we have to begin somewhere, and the question who is speaking the poem is as good a place as any.

RITA DOVE

1987 Winner, Thomas and Beulah (Carnegie Mellon)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

When I was about ten years old, my 4th grade teacher asked the class to produce something creative for Easter. As a voracious reader, I had pillaged my parents' book shelves and found Louis Untermeyer's Treasury of Great Poems, so I decided to try a poem. My title was so catchy—"The Rabbit with the Droopy Ear"—and had come to me so easily that I started scribbling out quatrains with no idea how I was going to end the thing! But I was having so much fun that I kept on writing until the rhyme scheme actually led me to the resolution. From that day on, I was hooked.

If it has, how has winning the Pulitzer changed you or your work?

I doubt that the Pulitzer has altered my work in any easily determinable sense. The recognition and acclaim it brought, however, did change my life—and therefore, of course, must have influenced my writing. One thing it certainly forced me to learn, as a basically shy person, was how to relax in the limelight and become more extroverted.

ROBERT HASS

2008 Winner, Time and Materials: Poems 1997-2005 (Ecco)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

Began writing poems in grammar school. Began taking the writing of poems seriously when I was in graduate school, around the age of twenty-three or twenty-four.

What was the first poem you fell in love with? What was it that spoke to you?

I've written an essay about this. I don't actually remember the first poems that I fell in love with. That may have happened when I was in college, but I remember a first poem that wowed me—or the first several—one of which was Wallace Stevens's "The Domination of Black." It would have been in my freshman or sophomore year of high school that I came across it in an anthology. What spoke to me was that it sounded amazing and it felt like someone telling the truth, and a different kind of truth than was used to hearing or being told.

If you could invite three other Pulitzer winners (from any time in the Pulitzer's 100 years, in any category) to dinner, who would they be and why?

Three at the same time? Or three separately? There are several living friends who are dear to me and who have won Pulitzers and I'd love to have dinner with them, singly or together. And there are people dear to me and recently dead who have been honored with Pulitzers whom I'd love to see one more time. I'd specifically like to have dinner again with Galway Kinnell or Charlie Williams or George Oppen or Stanley Kunitz. I did once have dinner with George and Stanley, two poets of the same generation, not especially sympathetic to each other's work, both Jews with a complicated relationship to Judaism and Jewishness, both survivors of the Depression, veterans of the Second World War. George had been a member of the American Communist Party. Stanley had been an anarchist by impulse and anti-Stalinist, which I thought was right but was also a more comfortable position to take in the America of the 1940's and 1950's. We ate at the Hayes Street Grill and they both ordered grilled rockfish, one with lemon and butter, the other with a tomatillo salsa. They belonged to the generation after Eliot and Pound and Frost and Moore, the generation for which—Stanley said once—writing poetry was a kind of internal exile. They drank a Napa Valley white wine and agreed that the election of Ronald Reagan was a disaster. Of the great dead, probably Wallace Stevens and Willa Cather. I could imagine them getting along with Faulkner, of course. Imagine having a meal with Edith Wharton! I'm told Robert Frost tended to dominate dinner table conversation. Imagine having dinner with Marianne Moore, or listening to Eugene O'Neil and Edward Albee (or Rodgers and Hammerstein, or Moss Hart and George Kaufman) swap theater stories.

RICHARD HOWARD

1970 Winner, Untitled Subjects (Atheneum)

What I would really like to say is that my strongest advice to all would-be poets, some of whom may know this already, is that if they want to write poetry, they must read poetry. All kinds of poetry, including that from the past. Especially from the past. And more than a single poem by a given poet. It appears to be the case now that aspiring poets don't feel the necessity. With my students, many of whom are in fact very talented, I try to open up the world of the past. I hope to some effect in the future.

TED KOOSER

2005 Winner, Delights & Shadows (Copper Canyon Press)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

It's been seventy years ago, but I seem to remember all of my grade school classmates being introduced to poetry writing, and my mother saved a few of my early efforts. But it was in junior high and high school that I began to take poetry writing seriously. My first published poem, a ballad about a hot rod race, had been sent by a friend, without telling me, to a teenage magazine called DIG. I was sixteen or seventeen. Since those days I have had poetry on my mind pretty much every day.

What is the first poem you fell in love with? What was it about it that spoke to you?

Walter de la Mare's "The Listeners" was in an anthology we used in junior high English, and I loved the poem for its mystery. It's about a lone traveler stopping at a darkened house by the road and trying to awaken whoever's inside. I have since written many poems about abandoned buildings.

If you could invite three other Pulitzer winners (from any time in the Pulitzer's 100 years, in any category) to dinner, who would they be and why?

I would like to see my dear teacher and mentor, Karl Shapiro, once again. I wouldn't want any other Pulitzer winners to get in the way of catching up with Karl, who has been in the next world for maybe fifteen years.

If it has, how has winning the Pulitzer changed you or your work?

Winning the Pulitzer brought me thousands of readers that I would otherwise not have. Having readers for my work is extremely important to me.

When I am Asked

Lisel Mueller, "When I am Asked" from Alive Together: New and Selected Poems.

Copyright © 1996 by Lisel Mueller. Reprinted by permission of Louisiana State University Press.

GREGORY PARDLO

2015 Winner, Digest (Four Way Books)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

My repertoire of origin stories offers several options. There's the one about watching my mother, a commercial artist, design yellow page ads by hand for twenty years. In this one, the child I was wishes he could make visual art like his mother, and, failing to do so, uses words to describe the things he see in his head. There's another story about the adolescent trying his hand at writing rap lyrics, and wanting to do more abstract things with language—off rhymes, multiple nesting dependent clauses, and dense, for a thirteen year old, metaphors and similes—that an audience could best understand with the time for reflection afforded by the page. Another version I often tell features a post-pubescent teen who discovers that he can get the female attention he craves by indulging his penchant for emotional honesty. All of these are accurate and true.

What is the first poem you fell in love with? What was it about it that spoke to you?

My mother read Dr. Seuss to me from birth until I could read on my own. We had a full stock of Seuss and P.D. Eastman books. Aesop's fables also wormed deep into my psyche. But it was Robert Louis Stevenson's A Child's Garden of Verses, which my mother read to me routinely, and at my request. Stevenson's poem, "The Swing," was a favorite of ours. One needn't be a Freudian to notice a pattern of association here between poetry and mother love.

If you could invite three other Pulitzer winners (from any time in the Pulitzer's 100 years, in any category) to dinner, who would they be and why?

Can I have four? Robert Penn Warren would be a guest because, as a poet, critic and literary citizen/ strategist, he was brilliant and admirable and problematic. I'd invite Louis Simpson, who I see as a verse version of de Tocqueville for his analysis of American life. Born in Jamaica, Simpson was both Jewish and, if you subscribe to the American pseudoscience of race, black, but this would only be a conversation starter. Gwendolyn Brooks, because she was such an astute reader of human foibles, would keep everyone at the table honest. I'd pull up a folding chair for Wallace Stevens. (This is beginning to sound more like a poker game than dinner!)

They have all, intentionally and/ or inadvertently, contributed to my sense of the relationship between aesthetics and ancestry, what I think of primarily as the specious aesthetics of race. I'd like to set them all down to see if they could help me distinguish cultural ancestry from essentialism so I can better marshal the ghosts I have internalized in my own practice toward the Manifest Destiny of a comprehensive American aesthetic.

If it has, how has winning the Pulitzer changed you or your work?

Who could have such an experience and not be transformed by it? I wish I could say the affirmation has strengthened my confidence in my work, but the truth is it has made me all the more self-critical. I'm all the more vigilant for signs that I might be lowering my expectations for the poem because I know it will be received with this prestigious credential in tow.

KAY RYAN

Winner 2011, The Best of It: New and Selected Poems (Grove)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

Until my late twenties I had a push-me-pull-you relationship to poetry, meaning it pulled me to it and I pushed it away. By eighteen I had been introduced to the poems of Gerard Manly Hopkins and Emily Dickinson, and I had felt the shock of being reorganized by such arrangements of language. If a poem could do that, who wouldn't want to write one? Except to write one you have to engage your whole self, and I only wanted to engage a portion of my self. Thus for years I intentionally dabbled in the shallows. But the shallows slanted down into deeper water, and I slowly felt my weight suspended: I found I could move around a little bit in certain new ways. That is, I was learning that poetry can teach you to write it. So that's how I got started: gradually and then faster.

Winner 2008, Failure (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

What is the first poem you fell in love with? What was it about it that spoke to you?

The first poem I responded to strongly was actually a series of poems, "Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience." I read them for an English class on the Romantic poets and loved them immediately. I may not have understood why Blake stood out for me, or why this one sequence in particular, though I think I do now. They were mostly persona poems, written from the point of views of lost children, chimney sweeps and "Infant Sorrow," often enough pleading for "Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace." Their passion, immediacy and powerful sense of identification with the poor, sick roses, little flies, angels, Tygers and lost and abandoned children moved me enormously.

I imagine because I too was a lost child. I became a little obsessed with them, memorizing many of them (not an easy trick for a dyslexic!), reciting them to myself as a source of comfort and amnesty at difficult times. I loved also the fact that Blake was an artist and illustrated his own poems. My love of art and drawing led me to poetry early on. I surprised myself by remembering so quickly these poems that continue to hold such strong feeling for me.

If you could invite three other Pulitzer winners (from any time in the Pulitzer's 100 years, in any category) to dinner, who would they be and why?

The first dinner would be with Elizabeth Bishop, whom I met briefly in Cambridge, Mass. in the early '70s. I always regretted not having, or making, the opportunity to know her better, as friends of mine did. But I was certainly aware of her presence in this small community of poets and academics. The first time I met her was in San Francisco in the late Sixties at a friend's house. My friend seemed depressed and she attempted to cheer him up by making an origami horse out of a piece of newspaper and then lighting it on fire. Startled, he laughed and his mood magically turned for the better. I remember the light in her eyes, mischievous and wise, and I would enjoy the opportunity to ask her how she knew this was perhaps the one trick that would work. There are many other things I would like to ask her, of course. Most of all perhaps how she managed to turn that profound river of grief that ran through so much of her remarkable work into such joyous, magical language.

Ernest Hemingway would be another choice. I first started thinking of myself as a writer while reading him as a seventeen-year-old. His great appetite for life and the manner in which he challenged his fear with intrigue and courage deeply impressed me. It's a fascination that inspired my earliest poems. I think it was Norman Mailer who said that Hemingway's best novels contained the generous emotion of a good first novel, into which everything a writer knows, and feels, goes. I imagine the same can be said about first books of poems. I loved his highly stylized medleys of raw feeling. I didn't know it at the time but suicide was an important theme in my life, too, so there's a great deal I would like to ask him, especially perhaps how conscious he was of the role his father's death played in his work.

George Oppen would be the last invitation. I knew him well in the late Sixties in San Francisco, when he was both a mentor and early source of inspiration. There was a period of over a year or more when I enjoyed a good number of Friday night dinners at his apartment on Polk Street. It had a view of the bay, I remember, and he loved to tell stories about his long exile in Mexico and his friendships with other poets, such as William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, Lorine Niedecker and Charles Resnikoff. One in particular stands out, about his smuggling into this country an early edition of James Joyce's Ulysses ("like smuggling in gold"). I was in my early twenties and he in his sixties and too much of what he said is now lost, and now that I'm older than he was at the time there are certain things I would enjoy asking him, not the least of which is what made him give of himself so generously to a young poet who had little idea of who he was and what he'd been through. I was something of an exile from the east coast myself, and owned a curious relationship, as he did, with my personal history. I would ask him too about his relationship with J. Robert Oppenheimer, a second cousin I think, whom he mentioned once or twice (his parents changed their name to Oppen before he was born, I believe) as a passing thought. God but how I would like another opportunity at those passing thoughts!

Imagine all three at one table, the silences alone would be memorable, and beguiling.

Winner 2014, 3 Sections (Graywolf Press)

What is the first poem you fell in love with? What was it about it that spoke to you?

I first fell in love not with a poem but poetry, in the form of Mark Antony's speech at the end of Julius Caesar over the body of Brutus, which I read when I was thirteen, in a class. For some reason, because of course I'd read great poetry before then, it dazzled me. I took it at face value. I was a little too young to catch the slight, subtle curve of the irony.

If you could invite three other Pulitzer winners (from any time in the Pulitzer's 100 years, in any category) to dinner, who would they be and why?

Carl Sandburg, Edward Arlington Robinson, and Robert Frost. They were fixed in the curriculum when I was growing up in Ohio, and were the first American poets I remember reading. It's hard to understand now, their presence in the culture. Who are they, exactly? It would be interesting to find out. Frost we know, but Robinson and Sandburg were just as famous when they were all alive and writing. Robinson is a wonderful poet, and Sandburg was surprisingly sophisticated. He appreciated and praised Pound in the pages of Poetry magazine when Pound was starting out. His poem "Fog" is the first poem I remember as a poem. I must have been shown it in the fourth or fifth grade. I'd also like to meet Vachel Lindsay, though he didn't win a Pulitzer. I still know the beginning of his Lincoln poem by heart, and the beginning of "General William Booth Enters Into Heaven"--William Booth founded the Salvation Army--which Stevens made fun of with his title "Lytton Strachey, Also, Enters Into Heaven."

HENRY TAYLOR

Winner 1986, The Flying Change (LSU Press)

When and how did you begin writing poetry?

My parents approved of poetry, kept a considerable amount of it in the house, and wrote a little themselves. As a child I was encouraged at home and at school to memorize poems, and in boarding school I wrote a handful of standard adolescent dreadfuls. In college I had the great good fortune to encounter an informal, non-credit poetry writing group headed by the late Fred Bornhauser, who put us through various formal hoops, guided our reading, and led us into the spirit of the craft. I had later significant encounters with other important teachers, but that was the beginning, and I've been grateful for it ever since.

What is the first poem you fell in love with? What was it about it that spoke to you?

Did I actually fall in love with any of the poems I memorized as a grade-school pupil? "The Highwayman"? "The Cremation of Sam McGee"? Not the way I did when my father read aloud to me E. A. Robinson's "Mr. Flood's Party," which combined a quirky but compelling narrative with a verse that was both formal and conversational. I have often thought since about the poem's other qualities, but those were what mattered to me at the time, which was the summer I turned sixteen.