In Their Own Words

An Unexpected Package: On Szilárd Borbély

In January 2011, on a cold winter day, a small package appeared in my post box, postmarked Debrecen. Packages often were exchanged between my address and that of the Borbélys: notes, presents for each other's children, letters, and cards. This one, like many others previously, arrived in a standard white envelope with bubble-wrap on the inside. It was the same envelope that I had sent previously, only my hastily scrawled address had been crossed out, and on a piece of white paper taped to the front was the return address and our home address in an elegant hand in black ink. Postage costs, it was clear, came to 1000 forints, expressed with two different kinds of stamps, each picturing a specific Hungarian chair, one purple and the other blue, from the Decorative Arts Museum in Budapest. One of them is designated as "The armchair of Pál Esterházy (1687-1725)" — in fact I'm not sure if that designates the lifespan of Pál Esterházy, or for how long he sat in the chair (probably the former). The contents of the package, however, were unexpected: when I open it up I saw a slim, rectangular, hard-covered diary, with beautiful purple endpapers, surely not marbled, but printed in such a way as to seem marbled. When I turned it open to the first page, I saw the printed words: 1998, and then:

Napló

Agenda

Tagebuch

In the right-hand corner of each page, a small quarter-circle had been punched out, so that the user of the diary could easily rip it out, thus keeping track of the days. I noted that none of the circles had been ripped out. It didn't seem as if this book had ever been used as a diary: there were just a few scattered notations of books, titles, addresses, people. Facing that title page, with all its italicized dynamism and hopefulness so reminiscent of the 1990s in central Europe, was a brief note, addressed to me, and composed in that same black pen, stating:

This is the diary in which I began to write the pieces forBerlin-Hamlet. Oh, it was so difficult, I was really afraid. I thought that I had [*lost] the manuscript. I found it in December, when I was cleaning out the garage. With affection and gratitude, Sz.

Berlin-Hamlet had been the very first work that I translated by Szilárd Borbély. I had met him for the first time at a translation workshop in Hungary in 2003, where I was deeply impressed by his presence and the volume of poetry he just published. My progress on this volume had been slow, I often pestered him with queries, but by this time was already hard at work on two later poetic volumes of his.

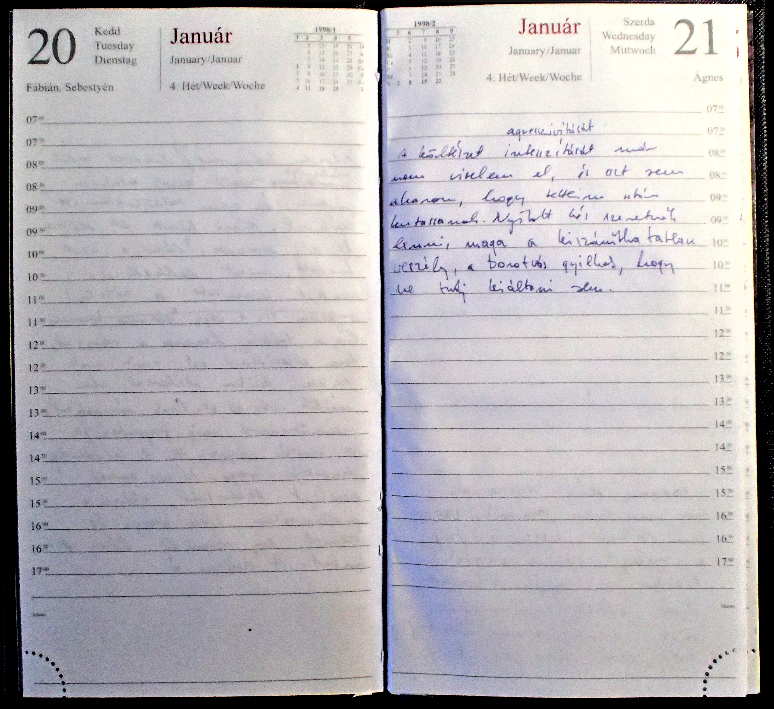

In fact, the diary only covers the first two months of 1998. Each day has a full page to itself, with the lines numbered from 7 am to 5 am. Beneath that, there is a blank space for memos. On the page for January 24, there is the notation:

The lyric text is always very aggressive. –

Three days before that, on the page for January 21, Borbély had written:

I cannot no longer bear the intensity/aggressiveness of poetry, and I don't even want my deeds to be investigated. I would like to be an opened knife, incalculable danger itself, the razor-wielding murderer, so that you can't even cry out.

These lines are written more or less as one paragraph, without the line breaks of the final poems, as are all of the manuscript versions contained in the diary. This is clearly the first version of the poem 39. [Fragment VIII] in Berlin-Hamlet, which reads:

I can no longer bear the aggressiveness of poetry,

and I do not wish my deeds to be investigated.

I would like to be an opened knife: the inscrutable.

A razor-wielding murderer. With a tongue oozing flattery, who drips

poison into your ear. Who makes you mute, so you cannot

scream. As the guards turn into the corridor,

I count five steps. Now is the time to cry out. Before

they throw themselves on me. Then in the stillness, there are no sounds.

In fact, if we lay the first notation over the final version, like a template, what emerges is this:

I can no longer bear the aggressiveness of poetry,

and I do not wish my deeds to be investigated.

I would like to be an opened knife: the inscrutable.

A razor-wielding murderer. With a tongue oozing flattery, who drips

poison into your ear. Who makes you mute, so you cannot

scream. As the guards turn into the corridor,

I count five steps. Now is the time to cry out. Before

they throw themselves on me. Then in the stillness, there are no sounds.

The kernel of the poem clearly lies in the sudden repugnance for the aggressiveness of poetry, which causes the poet to wish he were an unsheathed blade; it leads him to desire murder. And yet, despite his repugnance, he still has a need for lyric: "With a tongue oozing flattery, who drips / poison into your ear. Who makes you mute …" What was missing, now filled out in this final version, was the precise method of victim-paralysis: poetry itself, the tongue that oozes, that wheedles. It seemed that the poet was dripping the poison into our, the readers', ears. Suddenly, though, he is no longer the murderer, but the victim, counting the steps of the approaching guards, and somehow proffering the strangely decentered advice to cry out—to whom? His own self, disassociated? Advice that is not even offered as an imperative, as the situation might seem to demand, but the fairly weak kellene('should, would be'; which for various reasons I chose, however, to render in my translation as 'Now is the time to …') What is to come is known: they will throw themselves upon me. Then a voice notes that there are no sounds: no one cried out, the space of the poem (the prison corridor?) is silent, only the words noting the silence and the lack of words. Maybe it was registered (by whom?) that crying out would have been futile anyway. A Hegelian-minded analysis could note that this short poem follows a nearly perfect dialectal progression, from would-be murderer, to victim, and then the strange voice at the end who is neither, who has transcended both (or has been subsumed by both). A Kafkian demise: "As if the shame of it outlived him"—silence has outlived the poet. But the poet still takes note of the silence.

Borbély's insistence on raw and almost surreal physicality—a "tongue oozing flattery," as if it were detached from the rest of the body, is a trait well known to his close readers. Language as such is murderous. Very often, murder does not happen without being preceded by language: murderous thoughts, murderous plans — those singled out for murder are almost always marked first by language. As in the poem above: "I would like to be an opened knife." Borbély was to explore this theme much more intensely in his "Psyche and Amor" sequences (which comprise the second volume of Final Matters [Halotti pompa, 2006]). In one of the sequences, entitled 'The Emblem of Voices', Borbély writes:

Language is cruelest of all. It is inhuman.

Nothing but the interplay of signs and grammar's

sterile order. Not a single person owns the language

that he speaks, but in speaking, merely receives it as a

loan. In doing so, the body is first visited

and then seized by the Voice, that ruthless

God, just as Amor seized Psyche.

In a sense, then, [Fragment VIII] represents the triumph of silence over language. It came, it oozed flattery, and its murders, but the poet renounces language in the last stanza ("Now would be the time to cry out"), and so silence is all that, in the end, remains.