In Their Own Words

Timothy Donnelly on Richard Howard

A Conclusive Experience (1860)

Today he had decided it would be

not just his duty but his due: to climb

the five flights (literally flaggings,

even for a lad of seventeen) up

from the basement atelier out of which

William Morris Hunt tempted (or inured)

the raw youth of New England

to that loftier realm, his Life Class. Till now,

Henry James Jr. (that much a raw youth)

had obsequiously confronted those

plaster Accomplished Facts, replicas

to whose white conclave he had been assigned.

Was “confront” a verb for efforts of art?—

confront, sidestep, even hinder . . .Till now

it was anyone’s guess: alone with these

impassive casts, Harry had hoped he might

possess what they were marshaled to suggest:

not facts but a Vision. Armed with their blind

reassurance, could he not add (indeed,

in some cases, even subtract!) himself

till Matters of Talent would be, if not

given, at least taken? Even as a gift,

talent must be graced if it was to show

favor, the capacity to render

(another verb of art which always seemed

to be invoked upon occasions of

passivity, submission, or getting

rid, somewhat indelicately, of fat . . .)

Today had seen the best of his efforts:

not just the outstretched hands (as in

Apollo fondling Daphne just before

the bark began); or the enveloping

thighs (as in even a plaster-of-Paris

Paris), but in the whole a tergo rape

of Ganymede by the gypsum Eagle:

surely he was ready: not just life, but

Life Class! Now for the final flight of stairs,

conscientiously carpeted as if

even the approach to mastery

had to be muffled, all uncertainties

of accomplishment passed under silence,

as it were . . . And here was William! always

several steps ahead of his younger brother,

and John La Farge, engaged with charcoal

and that rough flesh-color drawing-paper

which appears, even chromatically,

to make itself signify. Already

Harry could hear that patient, irregular

rasp of silver-sheathed charcoal batons

even before he had seen what it was

they were working on. Or from. No one—

especially not Harry—could be heard

breathing. There, perched nude on a pedestal,

was Gus Barker!—beloved Cousin Gus,

“gayest as well as neatest of models,”

as James, dictating to Miss Bosanquet,

would say years later. And the sight brought down

all his illusions with a crash. Here was

something stared into realization

of which Ruskin’s lectures and his own

niggling with plaster casts took no account.

How often had his father dragged “his boys”

through the Pitti, and Harry never looked twice

at “Rubens’ great carnal cataracts so

palpitant with illusion.” After one

boy’s body rendered in his sight one hour

in Hunt’s attic studio, James said he

put his pencil in his pocket for good,

but asked for, and kept, William’s bad drawing

of dear naked Cousin Gus. The real thing.

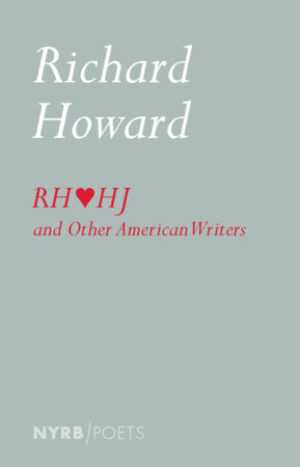

"A Conclusive Experience (1860)" by Richard Howard from RH Loves HJ and Other American Writers. Published by New York Review of Books. Copyright ©2020 by Richard Howard. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.

An excerpt from the introduction to RH Loves HJ and Other American Writers

by Timothy Donnelly

My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach,

With the twirl of my tongue I encompass worlds and

volumes of worlds.

Speech is the twin of my vision, it is unequal to measure itself,

It provokes me forever, it says sarcastically,

Walt you contain enough, why don’t you let it out then?

—Walt Whitman, from “Song of Myself (Section 25)”

Like meteors and peanut butter, poetry exists. Poems exist. A meteor exists, except sometimes, apart from the human. We prefer it that way. Peanut butter, on the other hand, is made by humans and is meant to be consumed by them. All the same, it is no less itself when the substance of it sits uneaten in its jar. It’s still peanut butter. A poem’s substance is typically just ink on paper. That’s where we, the readers, come in.

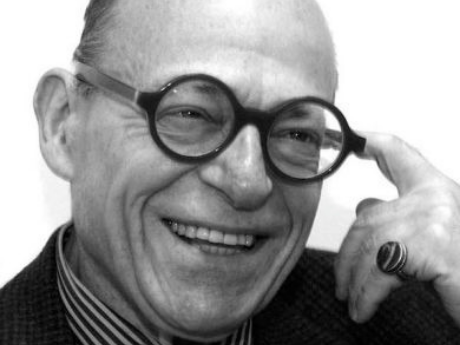

Poems are made by humans to be experienced by humans. Even the most private and elusive among them call for a reader to realize their nature. In this respect, if not others, the poem is a form of sociability: they call out for a reader. Otherwise they are not what they are. Probably no single postwar American poet’s work foregrounds the sociability of poetry more powerfully than Richard Howard’s does. His poems are full of broad, fine, unmistakably human voices; they are frequently dedicated to, and pay homage to, other humans and their achievements; they preserve the human past, trust in human intelligence, and, simply put, flatter the whole human enterprise by taking it very seriously.

They also make things up. They play around. They magpie. They peacock. They pretend. They refuse to leave things alone. The human impulse to transform the given, to engage creatively with the things of this world—to keep, to care for, to set apart, to adorn, to elevate, to adore—propels Howard’s poems. In this respect, as well as others, they are acts of love. And the things that are gathered in this collection, as its title affirms, are love poems, acts of adoration for those who have come before. And for Richard Howard, no one comes before Henry James.

Fittingly, the first of the poems collected here, “A Conclusive Experience (1860),” recounts a well-documented event in the life of James himself. Having been exposed throughout his youth to the “white conclave” of classical statuary via John Ruskin’s lectures and various plaster casts (but to no great effect), James was one day escorted ceremoniously to the top floor of an art school in Newport established by the painter William Morris Hunt. As Howard presents it, here Hunt and his students, including James’s older brother, William, drag their charcoal pencils across the “rough flesh-color drawing-paper,” busily engaged in “Life Class.” Double dense with meaning, a phrase like “Life Class” is honey to the bee (or bear) of Howard’s imagination, suggesting not only a place where humans might collect to draw from life but one where they might draw conclusions about life as well.

Much of Howard’s enterprise is fueled by this duality. His poems concern themselves, often, not merely with taking a look at reality but with taking a look into it. Each of these pursuits demands its own kind of vision—one sensory, and the other not exactly moral, at least not in any regulatory sense, but very much having to do with values, and with how and what we come to value. Certainly the senses are as important to Howard as they are to any poet, if not more so, but it is this second kind of vision that is perhaps more crucial to his poetry, which so often insists that art does more than just point at life, it points us back in life’s direction, orienting us toward it a little modified and readied for the encounter.