Interviews

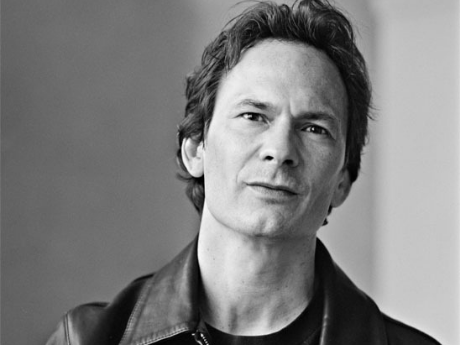

Poet Novelist: An Interview with Forrest Gander

Forrest Gander is the author of numerous books of poetry, translation, and essays. In 2008, his first novel, As a Friend, was released by New Directions Books and it has since been published abroad in French, German, Bulgarian, and Spanish translations. The Poetry Society asked Forrest about his experience as a poet writing a novel.

* * *

The four sections of this slim novel are written from different perspectives and in different styles—the first the relentless narrative of a birth; the second Clay's recollection of his fascination with Les, a virile poet who works with Clay as a land surveyor in the small southern town of Eureka Springs; the third a collection of lyrical fragments describing the grief of Sarah after Les commits suicide; and the fourth, "Les: Outtakes from the Film Interview," finally presenting snippets of plain talk from Les himself. One has the feeling of moving farther from conventional prose as one moves through the book. So I wanted to ask you a few questions about classification: what makes this a novel for you? How and at what point did you decide it would be a novel—did you set out to write one? And what, in your mind, distinguishes a novel different from a long prose poem? What is the importance of this distinction?

Despite the way mainstream books are sold, genres are, of course, porous and I'm not invested in defining or sustaining them as either writer or reader. I wanted to write in a way I had not written before: to begin with characters modeled on people, to begin with a story. I think those aims can be accommodated in poetry, but I am mostly a lyric poet and my poems aren't driven by stories or characters. I also wanted to explore a kind of sentence that might allow for a slackening of the tension and compression I associate with my own poetry in order to stimulate different rhythms of information and perhaps another level of readerly involvement. At first I called the work "a harmonic," but not even New Directions was sanguine enough to try to market something called "a harmonic."

Twenty years ago, when I started it, I tried to write As a Friend as more of a conventional novel, but after decades of failure, I came to realize that instead of trying to turn myself into another kind of writer, I could use many of the skills I had developed as a poet to write this book, this story, in a unique way. The section spoken by Sarah, with those abruptly juxtaposed small paragraphs (modeled, to some extent, on Wittgenstein's serial propositions and on David Markson's "novels"), may come the closest to poetry. If someone wants to say it is poetry, I don't mind. But for me, it feels like something else.

The magnetic central character of "As a Friend," Les, is a poet. But, at least from the perspective of Clay and Sarah, who narrate the story, "poet" seems to define a character (brooding, intellectual but with a naïve sense of wonder) more than a writing habit. While the reader and the narrators alike are hyper-aware that Les is carefully composing a life—"He would punctuate the remarkable things he said with silences, his extravagant gestures with absence"—his writing doesn't make an appearance, and his voice only in the final part of the book, after his death, disembodied, as edits from a film interview. So I wonder what you are implying, about poetry and poets—that a sort of mythology builds around the art? That poets are a self-mythologizing bunch? Have either of these been your own experience?

Wow. This is a hand grenade of questions. For me, the problem was like the task of defining poetry: as soon as you say what it is, poetry defies you. Someone holds up a contrary example. Any definition limits it. So I certainly didn't want to braid the novel with my own poetry as examples of Les's poetry. I wanted the reader to become the poet, to imagine into being the poetry that Les writes.

I came to think, finally, that Les had to remain enigmatic, just as poetry is enigmatic. It doesn't tell all of itself and what it tells is slant. And we see it most clearly slantwise. We learn nothing from holding a flashlight to its heart. In the novel, we see Les through Clay and Sarah. But this mode of telling the story is also connected to my interest in structuring the novel around a missing center and in the psychology of a character whose convincing mystique may conceal a vacuum, a character who, though massively loved, considers himself unloveable.

Are poets self-mythologizing? Everyone is self-mythologizing, poets no more than the rest. When you get to the point where you trade your life in for your myth, though, that's the moment of tragedy.

The section narrated by Sarah after Les's death is a non-linear collection of poetic fragments, pieces of a life recollected after its shattering in an accusing, elegiac second-person. To me, it recalled the Japanese Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon—so intimate, direct, and beautiful. Was Sarah the poet here, all along?

I like your reading. There are people, and Les is described as one of them, whose real genius is to bring out the latent talents in others. We love them with a kind of selfishness because, in their presence, we manage to shine with our own light as never before. Somehow they open up our faith in ourselves. As when Jesus' disciple Peter finds himself walking on water because, in the presence of his friend, he suddenly believes he can do this extraordinary, impossible thing. In As a Friend, Les brings the other characters into swift contact with themselves. Clay encounters himself stripped of all illusions, a kind of forlorn Iago. Sarah finds depths in herself that include her poetic voice.

The obvious question, but one that holds a certain fascination for poets: how did you think the process of writing a novel differed from the process of writing poetry, or your prose essays?

It was completely different the first time. I had no sense of how to invest literary characters with qualities that would make a reader want to keep reading about them. I had no sense of how to pace a long story, how to shape the energy of a scene. It was easy for me to get lost in details. To slow down the momentum of events for the sake of language. That's why it took me so long to write. I felt awkward all along the way, just as I did when, a few years ago, I tried to take up ballet. But weirdly, I think those differences have diminished now. As I write a second novel and continue to write poems and translate, the processes begin to feel similar. It's still awkward, all of it, maddening, I hate writing. And I do it and something happens and I catch, for fugitive instants, some glint of hopefulness that I might yet do something worthwhile.

Last but not least, will you write another?

I'm almost through with another one now. It's called Chihuahua Splash. It takes place in the Mexican desert. Two people drive in and no one drives out. Or not right away, in any case. And not in the same car. It's longer than the first one. And it's a novel. Or does it sound like a parable?