Interviews

Unexpected Lines and Gradients: A Blue Dark, and interview with Fritz Horstman and Fiona Sze-Lorrain

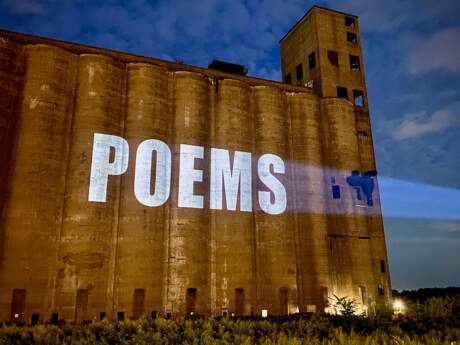

This summer, the Gallery Upstairs at the Institute Library in New Haven, Connecticut presents the show A Blue Dark, which opens on June 1 and runs through September 7. In this exhibition, visual artist Fritz Horstman collaborates with poet, translator, and zheng harpist Fiona Sze-Lorrain to explore a cross-genre range of textual/non-textual responses to the presence of a luminous dark. Both meditate on its changing physicality, materiality, space, emotions, images, meanings, and music by dialoguing with each other's work—ink drawings, poetry, and translation—inspired by the complexity of black, gray, and white, as well as their fluid mysteries of being. A limited-edition book A Blue Dark, published by Vif Éditions, featuring the work of Horstman and Sze-Lorrain is also published on this occasion. A smaller installation is, too, on view at Berl's Poetry Shop in Brooklyn from now until October. Here, both artists talk about their ongoing collaborative process, and how poetry and the visual arts become mutually inclusive influences in their lives, art, and friendship.

***

Sze-Lorrain: You started getting interested in making washi paper with plants and objects from your time in Onishi, Japan a few years ago. Could you share a little about the paper-making process?

Horstman: Making washi paper is a slow and beautiful process that has been practiced in Japan and elsewhere in Asia for many centuries. While I did visit two villages famous for making washi, and was able to try my hand at it, the paper upon which I made the drawings for our project was made by professionals. I don't think I could produce something nearly so fine.

During my time in Onishi I gathered many leaves and bits of detritus, soaking those things in ink, and making prints on washi. That is a different body of work from the Folds and Ink drawings.

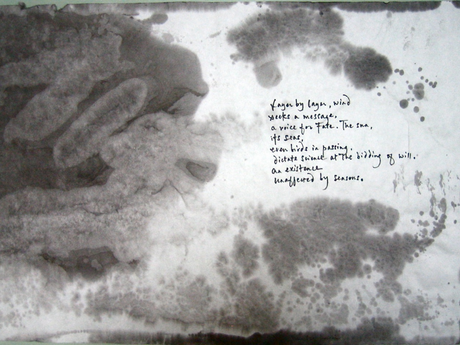

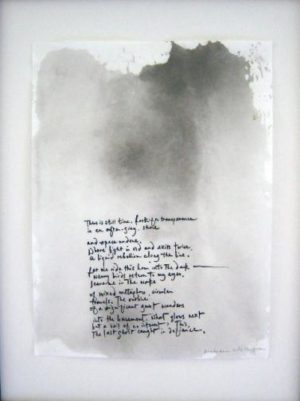

Sze-Lorrain: These ink drawings contain an inner life in contrasting ways. The papers that you had prepared for me to hand write the poems aren't just texturally intriguing, but lyrically engaging and deep in terms of visual ideas, flow, and abstractions. They invite me to read and write "alternatively." I need to stop thinking about poems and words in a "mental" zone or from a uniquely "writerly" perspective. In fact, I learn to think differently about space—and the interplay of words with emptiness, paper, and ink—by "practicing" the verses out in a concrete and physical way.

What came to your mind when you were working on the Folds and Ink series? How different was the creative process when you were treating paper for the handwritten poems?

Horstman: The Folds and Ink drawings began out of a curiousity about the materials of paper and ink. I had noticed how quickly sumi ink moved through washi paper. I folded a single piece of paper in half and applied fully-saturated ink with a brush to one side. The entire folded paper quickly became completely black. I couldn't see anything particularly interesting in the sopping wet paper, so I set it aside and forgot about it for a few days. Finding it dry on my studio table one afternoon, I peeled the folded paper open to see that the pattern in which I had applied the ink was quite legible, and that it had transferred through the folded paper with slight discrepancies. Naturally this led me to try other folding patterns, other papers, other inks and levels of saturation. I tried to avoid applying the ink in ways that would show my hand, at least in a painterly or expressionistic way. Of course my "thinking" hand is present in every fold and application of ink.

Because there is a degree of chance in this process, a great deal of editing is required, especially from early in the series when I was just beginning to understand how the materials behave. Perhaps there are thus far a hundred drawings that I have kept from a total of five hundred that I have made.

Folding and applying ink is a matter of strategizing about the physical properties of the material and setting up situations for the ink to move in interesting ways. In editing, or perhaps "culling" is the word, I look for lyric and evocative results, which also reveal some aspects of how they were made. You used the word "emptiness." Without a void left by the process there is nothing left at which to look.

Sze-Lorrain: Emptiness is a mystery and rigor. Poems look for that, and vice versa, but this doesn't suffice if in life one doesn't practice its ethics. It isn't the popularized "Buddhist brand" of state of mind or philosophy. I don't see it as an intellectual form of double negation, either.

When you first showed me the drawings in the studio, I saw in each piece a living poem: an organic work not of verbiage, but that can exist in and through the speech and demeanor of ink when it interacts with washi paper. There lies a rich range of vocabulary and silence. Beyond its figurative contents, each painting functions as if ink was being "embodied" on paper. How the fluidity and dynamics of ink made that possible on washi paper took me in on the spot. I thought at that instant that we could do something together, a hands-on exchange that might generate fresh ways of perception. It was a honest and spontaneous response to beauty at a specific moment.

Horstman: As our conversation turned to the possibility of putting together an exhibition, we quickly moved to the matter of how to best represent your words in a gallery setting. One exciting avenue has been the paper I have prepared using the same basic process as the drawings, but with the intention that your words will be written upon it. Using much less ink than in the drawings, and not holding myself to as rigid a folding program, I applied ink to a few hundred pieces of washi paper.

Keeping in mind that text would be the most important visual aspect of the finished work, I selected from those inked papers ones in which I saw intriguing space for text. Your poetry has a way of slipping in and out of shadowy areas, so I chose papers on which the ink had formed gradual transitions and veils, and which in ways that are hard to articulate seemed to have an affinity with your poems.

Was there a method through which you chose which poems went with which papers? Could you describe the approach you take to writing a poem? I'm curious if there is a general approach, or if not, if you could give a little insight into a particular poem's creation.

Sze-Lorrain: I didn't have a method, but some kind of a "progression" or continuum, yes. Lots of trials and errors, and failures, when it comes down to handwriting each poem. I looked at each paper every morning at a fixed hour. It became a discipline. I then memorized the ink touch and visuals. I looked at the reality before my eyes, and not arranging the reality to fit what I would like to see. The act of looking became listening, too. Sometimes a poem that could flow with the pictorial ink contents and paper came to mind easily. Sometimes not at all. I avoided inventing narratives between a poem and the treated paper. Resistance happened in other ways, too. For instance, by the time I felt ready to transpose the poem onto the paper, my breath and control of the calligraphic pen could go astray.

Since a child, I have been fascinated with handmade paper. I find it more an erotic medium than an object. It is tangible, but very forthcoming and informative. Its texture feels like traces of tactile memory. In our case, each treated paper is a unique piece, and must be respected. Once wasted, forever over. However hard I practiced at my penmanship, I would never find another paper and motif identical to the one squandered. I was aware of this stake every day during our collaboration. I kept things simple. One line at a time, but this doesn't mean being deliberate or slow; it is down to finding the nature and movement of the ink. Elegance isn't about aesthetics and mise-en-scène; it is being present and concrete, yet not taking up space on any level—mental, relational, physical, sonic, temporal . . .

I don't think the politics of word with image is about interference. In practice, boundaries are blurrier, much more elastic and unpredictable, but that isn't to say they can be mistreated. I go for the good surprises, and letting them become relevant. When we met in Bethany two years ago, we spoke about your relationship with poetry, and how visual artists in general might relate to poetry and the written word in general. I recall you mentioned American poets such as William Carlos Williams, Gary Snyder, and Howard Nemerov, in particular his "Because You Asked about the Line between Prose and Poetry," which I quote here in its entirety:

Sparrows were feeding in a freezing drizzle

That while you watched turned into pieces of snow

Riding a gradient invisible

From silver aslant to random, white, and slow.

There came a moment that you couldn't tell.

And then they clearly flew instead of fell.

What continues to draw you to this poem?

Horstman: In all of those writers there is a sort of reversal or inversion of an idea within a poem, and through that the process of making is revealed to some extent. Your poems often do something similar. I get excited when any work of art can show the process of its creation, and still maintain something lyric or mysterious. In the Nemerov poem I know from the title that there will be a comparison made. It is immediately apparent that he is using a metaphor to do it, but somehow he lets it unfurl line by line. When I get to the "reveal," if that's the word, in the final line, I still, having read it hundreds of times, get a thrill. This isn't to say that I actually understand how he wrote the poem, but I can see the moves he made. Your poem "Sixteen Lines: Autumn 2010" reveals itself in a similarly moving way:

In past autumns, I saw the world differently.

Swans looked graceful

because their bodies were white.

Crows were soothsayers—black

wings, black cries.

In those autumns, death was a small affair.

One leaf fell.

Another.

This autumn, death gets even smaller.

Leaves tilted by wind, into ashes of the earth.

Swans grow fatter,

dropping two or three feathers

into water.

Crows, mouthing air in bare elder trees.

Look: a long sundown.

No more black and white.

Sze-Lorrain: Do your ink drawings re-envision, to some extent, "the line between prose and poetry?"

Horstman: I think my drawings can, to some extent, be seen as hovering on a line between a visual analogy of prose and poetry. In Nemerov's metaphor, prose moves in straight lines following the law of gravity, while poetry, made of the same element, magically is able to float. I have subjected two mundane materials (paper and ink) to rules (folding and soaking) hundreds of times. The magic of it lies in the unexpected swirls, scrims, gradients, contrasts, symmetries and asymmetries.

***

Fritz Horstman has exhibited his photos, drawings, sculptures, and installations in recent exhibitions in Norway, Russia, Japan, Germany, and France, as well as art shows in Massachusetts, California, and New York. Currently, he is the artist residency and education coordinator at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut.

Fiona Sze-Lorrain is a poet, literary translator, editor, and zheng harpist. Her recent poetry collection, The Ruined Elegance (Princeton, 2016), was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her work was also shortlisted for the 2016 Best Translated Book Award and longlisted for the 2014 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. She lives in France.