New American Poets

New American Poets: Elyse Fenton

After the Blast

It happened again just now, one word

snagging like fabric on a barbed fence.

Concertina wire. You said: I didn't see the body

hung on concertina wire. This was after the blast.

After you had stood in the divot, both feet

in the dust's new mouth and found no one alive.

Just out of the shower, I imagine

a flake of soap crusting your dark jaw, the phone

cradled like a hand on your bare cheek.

I should say: love. I should say: go on.

But I'm stuck on concertina—

the accordion's deep inner coils, bellows,

lungful of air contracting like a body caught

in the agony of climax.

Graceless, before the ballooning rush

of air or sound. The battering release.

Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Introduction to the work of Elyse Fenton

Rachel Zucker

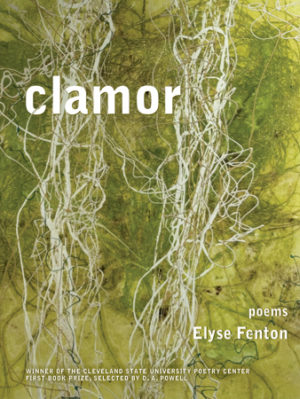

Elyse Fenton's poems are about something. That is, the poems in her book, Clamor, contain a discernible narrative and recognizable characters. The poems are about a woman waiting for a man to return from war and about what life is like for her when he returns. What makes the poems so compelling is the story she tells (both familiar and entirely new), the perfect forms she makes of her telling, and the space created between the story and the poems, which is an open field of speech, thought, desire and silence ("the saying, the not—"). There is a long history of women waiting for someone to return from war. Like many of these women, Fenton bides her time. She plants, she watches, she takes note. Carefully, carefully, she weaves her poems like Penelope at her loom. The making of poems is a way of marking time and of trying desperately to affect the passage of time.

Fenton's descriptions of her daily life and her imagined or overheard descriptions of events on the other front are hauntingly personal, moving, surprising. As a reader, I waited with Fenton for her beloved to return. I shamefully enjoyed the wait, the way waiting lends itself to a state of heightened attention and observation. I enjoyed the painful, precious suffering of longing. "O make of me a human/ camera to translate this restless flock," writes Fenton whose poems are a kind of camera, one that we both look through and look at, for part of what the poems are about is the inability to translate experience into language but the absolute necessity of trying. "I have to believe in more than signifiers—" Fenton writes, " that the world cannot be dismantled/ by word alone. That language is not an uncoupling dance…" There is a real "you" and an "I" (sometimes called "he" and "she") and they love each other. Can love or language keep them safe? If not, is it then meaningless? ("It happened again just now. One word/ Snagging like fabric on a barbed fence.") No. The poems do not make the war end, do not bring the "he" home sooner, do not erase the war from anything even when he does return.

But the words do matter, the word, any word, from or about the beloved matters so very much. The poems are a record of Fenton's fidelity both to her love and to language—no matter how difficult things get she is there with eyes and ears and heart open. The care and consciousness of Fenton's poems—lines, language, sound—is almost superstitious in its intentionality, but is never distracting or upstaging. Fenton is a poet with a story to tell; a poet finding the perfect forms to tell her tale. For example, when deployment ends the poems assume the shape of prose and even without line-breaks, they are crushingly beautiful, almost intolerably beautiful. The poems create intimacy even as they are always (even after his return) describing a kind of absence. The poems create a space where the poet and her beloved are together. Over and over but each time in new and surprising ways, Fenton brings the two fronts (the war and the homefront) together. She elides her present into that of the absent lover's present. In one poem her walls are "flower-mortared," and the leaf she presses into her wrist is the dog-tag that the soldier removes from a dead body.

There is both shame and pleasure in the poet's love of language, in the language of engagement, of war, of death, of destruction, but such care and attention on Fenton's part is necessary, admirable, for it is through the examination of the language of deployment and civilian life that readers such as myself, who wait for no specific solider to return and have only an abstract sense of war's ravages, can begin to feel the war.

Fenton's poems allow the war to be a metaphor for life, for waiting, for separation, for the way in which all couples are always separated in and by their distinct points of view and independent experiences. The poems also insist on specificity and are always about this war and this time, this "I" and this "he."

When I read Clamor I cried. When I read it again, I cried earlier and harder and longer. It is not often that a book of poems has this effect on me. I wanted to keep reading, to know what would happen and how. And, more than that, I wanted to keep hearing Fenton's voice, to savor her careful observations of the sun, the garden, bodies, longing, absence, presence—to marvel at her deft lines, to shiver as she brought the war home for me.

Statement

Elyse Fenton

If there were a mascot to my poetics, mine would be that Classical sad sack, Orpheus. I'd rather it be Pan, or, wishfully, Hippolyta. Even Medusa. I'd rather embrace mischief and play, courage and ferocity, but really, my poetry comes from a mode of lamentation, from an awareness of obsolescence coupled with the nagging human anxiety of loss. Orpheus' bargaining with Hades got him where? To some graveled underworld switchback to reenact his beloved's death.

Maybe poetry is such a practice in futility. We talk about it as an attempt to speak the unspeakable, to bring us back the world. And in this, it's a constant failing, for the material of a poem is language– that sometimes-flimsy, sometimes boulderish stuff–but it's not the world and it can never be. Of course, that doesn't mean I'm not trying to haul the dead up by a shadowy net, to exact some kind of equation, to tether word to world, to shepherd and shuttle. I just know that it can't– quite– be done. That proximity is a form of desire, and like any desire, it's simultaneously maddening and a delight.

And yet, here I am, living and writing in the world, and often writing back against the world or into the world or around the world. I'm busy prepositioning the world. Trying to swansong it back into my hands so that I might disassemble it again.

At its best (or perhaps, easiest, which is to say, hardest) the poem I'm writing hijacks me toward loss, and I let it. Why the hell not? There it is, broken down at the roadside, and I stop; I have to stop. I let it rough me up, shove me into some 80's beater, top up and all the windows shattered, a sound in the engine like the cough of a dying hive. Let me show you around, says Orpheus, and I already know where we're going. I'm already leaning idiotically out the window like the whole thing's a carnival, hitting the tinny panel with my hand, letting the dumb wind buffet my face until there's the synesthesia of blood in my ears and I can't feel or see or hear anything else. That, at least ideally, is where the poem begins.

But sometimes I get tired of Orpheus's gaunt loitering at the roadside. I get tired of pulling over. My hands grow mossy on the wheel, and I stop for nothing, no veering toward jersey barriers, no pausing for thinly mustached strangers. No risks. No rupture. Just a poem churning straight mechanical from keyboard to screen. A slight, clean wind at the back.

For, as it turns out, I require both processes: the looking and looking away. Form and recklessness, joy and loss, stoicism and play go hand in hand. Or perhaps damp fist in damp fist. A poem is both a record and a performance of dissonance, constantly at odds with itself. It embodies the impulse to swerve and not to swerve, the braking and the breaking free.