Q & A: American Poetry

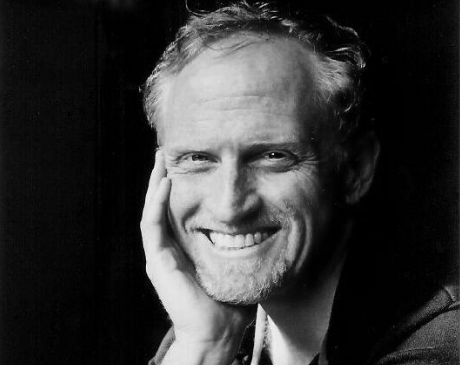

Q & A American Poetry: Campbell McGrath

NOTES ON AMERICAN POETRY

CHAOS

American poetry is certainly identifiable in the way American film or American painting is. Poetry feels even closer to music as a model, where America has invented entire genres and subgenres—jazz, blues, rock and roll, bluegrass—while also continuing to create work in inherited European forms. That is, an understanding of 20th Century American music would have to encompass Gershwin and Thelonius Monk, Son House and Joey Ramone. As the analogy suggests, one defining characteristic of American poetry is its diversity, its inability to be pigeonholed or represented by one or two major figures or models. There is no binding consensus on what is essential in our poetry right now. This superabundant complexity may seem maddening to those whose business it is to impose rational categorization upon disorder—namely critics and theorists—but to poets it ought to feel like an entirely welcome and delightful state of affairs. Chaos. Organic, productive, poetic chaos.

*

THE BRITISH & THE IRISH

In general, I see few similarities between contemporary British and American poetry. While there are some American poets who might be mistaken for British, no British poet is likely to be mistaken for American. The American vernacular, however multiphonic, is notoriously difficult for the non-native to master: think of Danish bluejeans, Sergio Leone westerns, French rock and roll. Even the Irish, who are in the midst of such a burst of poetic eloquence at the moment, are very traditional poets, and lack the diversity of perspective and the crazy energy so many American poets bring to the page. This must have to do with the differences in the cultures: Irish poets are still attuned to a voice that is rural, insular, pious; while Americans have the entire amped-up chorus of the corporate-driveby-infotainment regime from which to choose. There's been no Whitman figure in Irish poetry to enlarge the form; for that matter there's been no Dickinson figure to recast it so idiosyncratically. It seems relevant that the great Irish poets of the century—Yeats and Heaney—are conservators of the tradition, while the great Irish prose writers—Joyce and Beckett—have been formal revolutionaries. It's as if Joyce and Beckett, having begun as poets, somehow lacked permission to create revolutionary formal work within the hallowed walls of Poetry, or felt the sense of tradition too strongly, and so moseyed over to the unfenced pastures of prose to do their work.

*

NEW WORLD VS. OLD WORLD

I think American poets have a greater kinship with other poets of the Americas, and possibly there are Central or South American, West Indian or Caribbean poets who might be mistaken for American. Heaney and Milosz rarely read like American poets to me, but Neruda often does. Here in Miami I teach a lot of students who come from other New World cultures—Colombia, El Salvador, Trinidad, Haiti, Cuba, Brazil. These are young poets who write from a sense of cultural pluralism; they often write bilingually, and yet their poetic identities are clearly American. They are more likely to look to the poetry of Li-Young Lee for a sense of kinship than to a poet of their homeland. Poems my students write in Spanish or Jamaican patois still feel like American poems to me—it's in the cadence, the energy, the cultural database, the concerns of immigration, acculturation, Americanization.

*

BASEBALL, HOT DOGS, APPLE PIE & CHEVROLET

Personally, I consider myself an American poet, because I've been shaped and molded by the culture in ways both known and hidden to me. Thematically, I write primarily about American culture, history, and landscape; but even when I'm writing about parenthood or palm trees I understand my vision to be colored by my sociocultural identity. My poetry may be an extreme case, but I often wonder what value it holds for a reader unversed in Americana, a reader unfamiliar with 7-11s and cable TV.

*

CANONS TO LEFT OF ME, CANONS TO RIGHT OF ME

The canon seems to me to be multilateral, and, increasingly, multicultural. My personal canon would include prose writers, musicians, filmmakers and painters along with poets. When I think of my "tradition," of the actual craft of poetry, I think primarily of American poets, but it's a selective and personal list—Whitman and Dickinson, William Carlos Williams, Sandburg and Ginsberg. Sylvia Plath, James Wright, Elizabeth Bishop and Frank O'Hara are four major postwar figures I'd list as influences. I feel like they all belong to a kind of centrist free verse tradition, not part of any School or Movement, a diverse array of poetics occupying the roomy esthetic middle ground. The extreme camps of American poetry, Neo-Formalists on the right and language poets on the left, feel to me less "American" than the center. Both seem nostalgic for European models—the British and the French, respectively—and both have an inclination toward ideological exclusionism. True believers, on both sides.

*

THE WEALTH OF NATIONS

America owes the world some explanations, and in a culture famous for its lack of introspection, who better to provide such answers than our poets? Right now the nation is wealthy enough to support the luxury of poetry in a big way: there are an unprecedented number of poets in America, employed mostly as teachers, and our schools and universities are full of young people who would like to join them—throngs of smart, talented, many-tongued, multi-traditioned men and women fueled by our sociocultural chaos who want nothing more than to engineer new poetries from the raw material of words. The language, it turns out, is our truly renewable resource. Long after the last tree is cut, the last salmon slaughtered, the last fossil fuel burned, people will feel the desire to create poems and the hunger to hear them spoken. At which time it may be too late. But until that apocalyptic moment, when Kevin Costner stands revealed as a prescient artistic visionary, there is work to be done and plenty of eager hands to do it.

Published 1999.