In Their Own Words

Katie Marya on “Home in Las Vegas”

Targets, Best Buys, IHOPs and casinos—

everything a primary color except the stucco

cube house squatting on its track, the pride

my single mother paid for by herself, mostly,

which shouldn’t matter at this point—just look

at her trying so hard to make a normal life

for us: she stains the cement floor like mud

finger paint, an impromptu weekend project,

she switches on the electric fireplace for the dog

as we leave to pick up Chinese food so we can sit

in her bed and watch HBO, that’s what we do

on Sundays. My prepubescent body wrapped

in booty shorts and a Bon Jovi t-shirt curling

next to her. She makes dinner sometimes,

always pork chops and green beans. Every night

is the end of a hard day. Once we had a pigeon

problem, shit covered the patio—watch her sprinkle

Alka-Seltzer everywhere, even on the phallic yucca,

and whisper those birds will nibble up these chalky

pellets, fly far away, and blow up. She rearranges

all the wrought-iron furniture, spruces up the beds

on the floor with no box springs, stocks the pantry

with perfectly lined boxes of Cheez-Its, Slim Jims

and vitamin C. And here I am now telling you

about the shape of me beneath her feather

comforter, our luxury, and the pigeon plucking

and blinking at the skyscraper palm tree, how

that whole world she made came and went so fast.

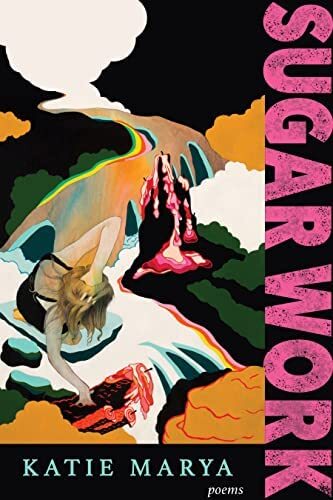

Reprinted from Sugar Work (Alice James Books, 2022) with the permission of the author.

On “Home in Las Vegas”

I can’t remember the genesis of this poem, but an image comes to mind. One summer, probably ten years ago now, while I was home for a holiday, my best friend and I drove to our high school. We wanted to sing the songs of our adolescence and remember how and what we’d survived as teenagers. To get to the school from our neighborhood, you drive down Rainbow Boulevard and across Highway 215—a belt that circles the outer rim of Las Vegas. When I first learned to drive, this highway felt like what I’d imagined as the Autobahn in Germany. People went fast. In some spots, the highway edges the mountains that frame the valley and while on it, you see down into the city, into the desert turned neon, all its stucco suburban sprawl spreading out from the Las Vegas Strip, that infamous row of hotels and entertainment in the center. To get to our high school, though, you cross this highway and watch the Strip in your rearview mirror get smaller. While growing up, my school felt like it was on the outskirts of the city because it was outside Highway 215’s rim. Nothing had been built that far out yet, and on this trip home, while cruising Rainbow right after we crossed the 215, as we say, an entire shopping complex seemed to have sprung up out of nowhere. Petco, Target, BestBuy, a movie theater, Jamba Juice—it was all there. The bit of desert that felt untouched when I was younger was different, and the image of that shopping center at dusk, all the streetlights on, is what comes to mind now. This is where the poem begins.

I do not believe one place is more chaotic than another. Perhaps this is misguided, and I’ll change my mind. I know my childhood wasn’t quite a childhood—there was mania—and I am never sure this is something to grieve or simply accept. I do know my mother tried in that shiny arid city to make a home we could be proud of, which is ultimately the driving force of this poem. She has since sold that house. Whenever I visit her now, in her and her partner’s newer, fancier home, I always want to go past the old house and drive to the high school’s empty parking lot with Sarah. What feels familiar is my mother’s body, Sarah’s body, and the parts of Rainbow Boulevard right around our old neighborhood. Mary Ruefle says, “the dream of all poetry is to cut a hole in time” (Madness, Rack, and Honey, 237). I rummaged through first drafts of this poem, and I appear to have started writing it in June of 2015, which was the beginning of huge life changes for me, perhaps the first in my adult life. Changes that were all my own and not a consequence of my mother’s life. I suppose the genesis of this poem, like most of the poems I am writing now, comes from my desire to preserve some sense of home.