Award Winners

William Carlos Williams Award - 2022

Patrick Rosal

The Changing Hymn (Allegory of the Singing Lover)

For Mary Rose

During the Trouble Years

my love sang the same song

every day but every day

she’d change—slightly—the words

One day she sang a song for sweepers

and the next day the sweepers became

hangmen On Friday the hangmen turned

into willows In September

the willows turned back to broomsticks

broken in the hands of janitors

She and I used to play a game

waiting for the ferry or on long walks

to my auntie’s house One of us

would begin a song

and the other would repeat the line

changing just one word—

back and forth like that—

drawing and redrawing the images

in the lyrics each time growing

an extra eye or tongue or

losing a foot one word at a time

The game gave us nuns (whom we loved)

on skateboards and who ate steamed buns

in Muncie where they confessed

to the Best Western desk

they were once boys who were once

orchids who were snakes first

slithering through midtown palaces

blazing on trains turned

rocketships in Oxnard and tractors in Parlin

before straddling massive salamanders

in Paris where the sisters farted

on the heads of billionaires

and shook tambourines

in their yellow teeth before

they got down on their knees and prayed

And the cold mist of the ferry was

always good And the cold air between

our house and my auntie’s just as good

My darling loved most to sing

in dark places especially dank bars

packed with locals who were swift

to rise from their crummy chairs

and stagger to their feet setting their drinks

on the closest table or they’d simply

fling their glasses to the floor

to finally hold one another so close

they could sniff each other’s cheeks

though hardly anyone knew another’s name

My love put their tables in her song

and the backroom’s musty wood

and the dusty lavender smell of factories

beside the perfume of goat breath

like a gift inside the song

and sometimes the crowd

would swell into laughter all together

to see if such a singer and such a song

could hold the joyful sound

of a hundred strangers and

they would stomp and twirl

to see if their dance

could keep up with my love’s song

and with all their singing and swinging

stepping and sliding they forgot

their walking legs and their meat hooks

and the thick pine smell

that haunted their saws

my lover’s song so fearless

sometimes the dead got up too

for even the most crotchety of our elders knew

if we opened ourselves up

wide enough to the song

the song would not leave us

even lying down

and this is how

her singing became a country

that could go everywhere

a vagabond that moved through

whoever welcomed it This is how

a song became a little nation

inside a hundred people

grooving so hard no one could say

exactly what a nation was—the land

the people upon it or the ones

buried in its fields and hills

for the dancers were pure tremor

cycle and vibration Migrants

they were pure wave

Sometimes short on rent my love

would sing for quick money

in big beautiful halls crystalline and sad

where the people were also sad

for their ties were always straight

and their clothes were well pressed

and they dared not scuff the good gleam

of their belt buckles—that kind of sad—

they were so rich with the wealth of silks

and platinum garland and fast boats

The marble floors of their salons

so clean you couldn’t tell a single

blade was put to wood

or that a drop of blood had fallen

on their shiny tiles

No evidence

of the making

but by god

when my love sang every one of these

bright-buttoned folks would sway

barely budging at first

so you couldn’t notice the ghosts

stirring inside them

like a sugar starting to cook

into its first kick of liquor swirling now

nudging them like a sweet inner fog

They tried (Oh did they try) not

to let the rhythm in They gripped

the tables’ silver in their fingers

and curled their toes inside their shoes

And just as the music got into their stiff hips

their bodies relented It was then

my love would begin to fit new words

to this familiar tune And clever

she would hide me inside the song(!)

maybe just the crook of my neck

or the pink scar across my forehead

(which she’d touch to calm me

when I was sick) Sometimes

she’d smuggle into the song

my busted up pinky my bruised feet

or my father’s piano And I would laugh

even louder when the coiffed ones laughed

so hard and loose they seemed

to be breaking all their great grandfathers’ rules

for even the powerful understood

the power of what’s hidden

how a woman’s voice of wild harps

and charging horses was guiding

this monster of a song inside them

while all us savages and outcasts

rode stowaway tucked into the tune

with all our fists and all our feet

and all our sweat and grime

soiling their powdered armpits

and fancy panties in public

And when my love finished

they would suddenly close up like

a patient quickly suturing himself shut

At the end of the night

their long candles burned to their bit wicks

a few of them would approach my love

and shake her hand as if

she had only one arm They’d thank her

as if she had no eyes to kiss

and she would tell me going home

she knew the song would not

stay inside them the way it seemed to abide

in us that spirit which makes

the hammer and hoe blade ring

and the hospital’s faucet water

so cool to the lips you might lick the spigot

and the engine of the trolley rattle hot

this very old spark of the body working

and working and working

it all on out

And there were mornings—though awake—

my love would lie in bed like empty luggage

For many nights she moaned in her sleep

as if the song were leaving her for good too

But then in a week or month often

after the winter cold lost its sting

to the first gingko buds

we’d lift our heads at the same time

and hear a small breaking

the cracking

of a crate smashed glass and crystal

which gave way to flutes and cuckoos

the heavy steps of old ghosts

to keep the new ghosts company

This widening country of wandering bodies

all the sound through which she roamed

and every sound which roamed within us

she made and unmade and remade again

in the Trouble Time everything

she sang and unsang out of fevers and blood

where no one was ever lonely

She never wanted others to be lonely

She sang so no one would ever

be lonely

I’m speaking in the past

as if we will never exist again

and yet

every song changes

as it goes We’ve already begun

to turn into tomorrow

We are the soonest sounds to come

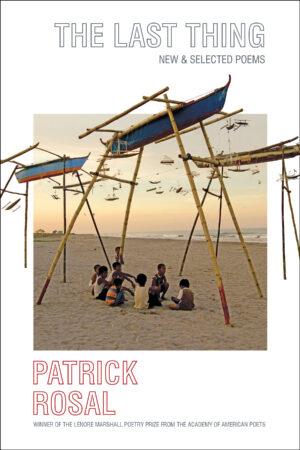

From The Last Thing: New & Selected Poems (Persea Books, 2021). All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of poet.

Erika Meitner on The Last Thing: New & Selected Poems (Persea Books)

Reading Patrick Rosal’s The Last Thing: New & Selected Poems is an embodied experience; these poems jump off the page with a muscular exuberance. You can hear their raw emotions singing in your gut, and feel their language in the sway of your limbs. These are poems that aren’t afraid to pitch their bodies onto flattened cardboard to pop and lock and spin, creating a new vernacular as they go that’s kinetic and visceral. “Shame / is like you’re made / of 10,000 beautiful doors // and every day / you try to keep them / all / from flying open / at once,” he writes in the title poem, and The Last Thing contains over two decades of poems—not only Rosal’s greatest hits from Brooklyn Antediluvian (2016), Boneshepherds (2011), My American Kundiman (2006), and Uprock Headspin Scramble and Dive (2003), but also 60 pages of new work that cement his legacy as a virtuoso poet who creates banging standalone showstoppers.

And while each poem in here is its own self-contained world, having them proximate between these covers allows the breadth of emotion, language, music, and range of Rosal’s forms to shine—the elegies and love poems, odes and narratives, laments and hymns, aubades and kundimans, prayers and letters and incantations, call-and-response, parables, and lists. We move from America to the Philippines and back again, through the streets of Jersey and Manhattan, with poems that bring the world into them to push “the fluid boundary between storytelling and song,” as Rosal writes in the stunning preface, which also meditates on oppressive systems and the nature of poetry as a language of resistance. Rosal is a poet who is unafraid of emotional imperatives and is as attuned to justice as he is to the breath and integrity of his lines. In “Bienvenida: Santo Tomás,” he tells us, “Sometimes / we have to sing just to figure out / what we cannot say.” Rosal’s is a poetry of grief and loss, survival and perseverance, as much as it’s a poetry of ecstatic joy and humming eroticism. I chose this book because it moved me immeasurably.

Purchase The Last Thing: New & Selected Poems