About

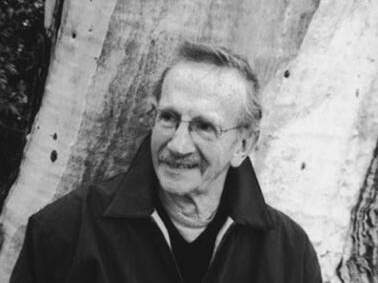

On Philip Levine (the newly selected U.S. Poet Laureate)

"Trust the poem not the poet," Phil Levine told our poetry writing class that spring, years ago, when I was his student. "Why would you believe the poet anyway?"

But I believed Phil. It was my freshman year in college. I wrote down everything he said, read and reread his work, and memorized his poems

"Trust the poem not the poet," Phil Levine told our poetry writing class that spring, years ago, when I was his student. "Why would you believe the poet anyway?"

But I believed Phil. It was my freshman year in college. I wrote down everything he said, read and reread his work, and memorized his poems.

Phil's class was different from any class I had ever taken—or have taken since. At my college, writing classes were infamously difficult to get into: at the first class meeting students did a writing exercise in a blue exam book and were chosen based on what they wrote. The first day of Phil's class, he told everyone who showed up they were in the class. His spirit of inclusion set the tone for the rest of the semester. Our class was composed not only of undergraduates but also a Professor from the psychology department and a songwriter who played his poems on his guitar. Discussion was lively and wide-ranging. Many of us went on to become poets and publish books.

Yet, what was most important about this class was that Phil gave us permission as writers and showed us how important poetry was. He encouraged us to write about what mattered most to us and helped us to see that poetry did not have to be focused on the beautiful. As he would write, later, in the wonderful poem "Coming Close," about a factory, "Make no mistake, the place has a language." Phil gave me—and still gives me—permission to write about Louisiana or Queens or any place I've lived. Phil taught us that where we were from had value and showed us that part of our responsibility as poets was to record the places and people who were disappearing, who were already gone.

Phil gave me permission in another crucial way. "Just write," he told me. "Stop worrying so much about being a writer." (I was eighteen and took myself much too seriously.) He told me to write about people I knew, about places I had been, and to quit thinking about where I would publish my poems. Similarly, as my colleague poet Ryan Black, who studied with Phil at NYU, recently recalled, "One night, after talking for a few hours about our terrible drafts, he thought to tell us all to slow down. It was simple advice, but I needed to hear it. "Don't be in such a rush," he said. "The world doesn't want it anyway," which I still find reassuring."

Now, each semester, at Queens College, I start my undergraduate and graduate poetry writing classes by assigning Phil's work to give students this kind of permission. On our public urban university campus where more than 129 languages are spoken, our undergraduate students are often first-generation college students, often immigrants, who work full time. My students are quite simply stunned when they read Phil's book What Work Isbecause, as they have no idea work—the kind they do, the kind their families do—can be the subject of poetry. For the graduate students in our MFA program, Phil's lessons are perhaps even more important. MFA Poetry student Drew Biscardi explained, "When I read Phillip Levine's poems I am reminded that poems are everywhere around us in the seemingly mundane and the overlooked. He reminds us as poets that we need to be ever ready, looking deeply at all the everyday chaos around us for the poetry that is contained in it, acknowledging that the plainest of moments and the humblest of people hold something deeply beneath their surfaces." This is what I most want to teach my students, what I take from being Phil Levine's student: to write poems that look beneath the surface of the world.

Levine's work and his presence show us how much poetry matters, how much our lives and the places we are from matter, and how much we can trust poetry to teach us about ourselves and our world. And even all these years later, I am still a student of Phil's work, it's toil and labor, because his poetry and presence show us how much poetry matters, how much our lives and the places we are from matter, and how much we can trust poetry to teach us about ourselves and our world.