In Their Own Words

Ishion Hutchinson on “Station”

Station

The train station is a cemetery.

Drunk with spirits, a man enters. I fan gnats

from my eyes to see into his face. "Father!"

I shout and stumble. He does not budge.

After thirteen years, neither snow nor train,

only a few letters, and twice, from a cell,

his hoarfrost accent crossed the Atlantic.

His mask slips a moment as in childhood,

pure departure, a gesture of smoke.

Along freighted crowds the city punished,

picking faces in the thick nest of morning's

hard light that struck raw and stupid,

searching, and in the dribble of night commuters,

I have never found him, wandering the almond

trees' shadows, since a virus disheartened

the palms' blossoms and mother gave me the sheaves

in her purse so he would remember her

and then shaved her head to a nut.

I talk fast of her in one of my Cerberus

voices, but he laughs, shaking the scales

of froth on his coat. The station's cold

cracks back a hysterical congregation;

his eyes flash little obelisks that chase the spirits

out, and, without them, wavering, I see

nothing like me. Stranger, father, cackling

rat, who am I transfixed at the bottom

of the station? Pure echo in the train's

beam arriving on its cold nerve of iron.

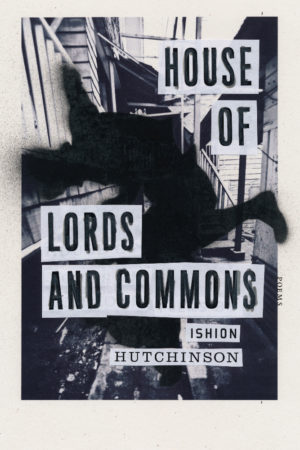

From House of Lords and Commons (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted courtesy of the author.

On "Station"

Aeneas's decent into the underworld. I return there often and it is the fractured, focal point of "Station." The poem's shaping music originated elsewhere, however, from a kind of tremor of reading this phrase in Book 9 of Paradise Lost: "Into a gulf shot underground; till part." The phrase contains one gasp, an O. The language hears what it sees. And whenever I am on a New York City subway platform (what is meant by "train station") I feel, in successive duration, the bolt of that main, sibylline verb. O! The shot of heartbreak, of homesickness, that in memory's logarithm intensifies that paradise of no return: childhood. Paternal severance specifically, which hinges on the precipice of forgetting.

In the classical tradition, there is no more moving evidence of that than the three times Aeneas tries to hug his father's shade on a green bank in Hades. I panic at that moment, here cited in Seamus Heaney's enviable translation: "Three times he tried to reach arms round that neck. / Three times the form, reached for in vain, escaped / Like a breeze between his hands, a dream on wings." The panic is hysterical; I hope, always, against hope that the father will disappear into the son.

But the moment passes quickly, without pathos, into a pedestrian display of spirits drinking to "obliterate[s] / all trace of memory" from the Lethe. To hurry on amplifies the devastating futility of the gesture and the pain of absence. To dwell there would have made the moment precious, symbolic. It is a moment that longs for fulfillment, but will never find it, and so must be returned to, again and again, to sharpen, somehow, the transitory brush of illusion with reality.

"Station" is such an attempt and could be seen—three stanzas, three hugs—both as a dissent from and a resistance to the Atlantic as a Lethean stream and a desire to keep a clean ear for memory, departing and arriving.