In Their Own Words

Isabella DeSendi on “Pep Talk for Medusa”

Don’t let the girls with straight hair tell you

you’re unlovely. Your kinky hair abominable,

pretty as a whip. Your hair hissing like rain

the sound shame makes when we sleep.

When I was seven, a girl touched my curls

and asked if I ever brushed them, if I had a mom,

where I was from. She meant who was taking care

of me. Who let me look this unruly. I told her

I too started girlish in the world

like poppies emerging feverish before

someone else’s hunger made me venomous

as a woman. At a party in Bedstuy, a Latina

with thin, straight hair will say we’re lucky

to be pretty, white-passing. She didn’t know

my curls were brushed flat, buried

beneath a slick nest of a bun. Answer me, Athena.

In how many languages will I have to apologize

for someone else’s gaze? Tell them it wasn’t my eyes

that killed anyone, but simply the reflection

of their own dark staring back at them.

After the party, I went home and showered

then stared in the mirror at my brown skin,

black eyebrows, brown nipples, dark cunt

wondering if anyone could see me clearly

and to whom I was god, monster.

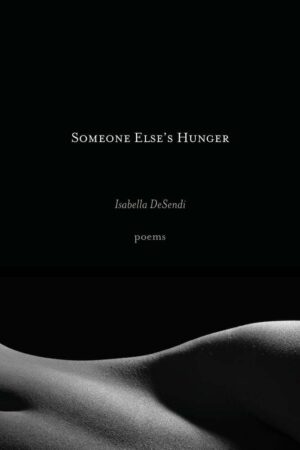

Reprinted from Someone Else's Hunger (Four Way Books, 2025) with the permission of the author.

On "Pep Talk for Medusa"

As the poem recalls, I was at a dinner party in Bedstuy when another Latina at the table, a girl with naturally straight hair, sat across from me and casually mentioned how lucky we were to be white-passing in America. My curls were combed back, “...brushed flat, buried beneath a slick nest of a bun.” There was no way for her to know that my hair was not naturally tame and subordinate, but big and thick and unruly, usually obscuring most of my face. My face—only this light because it was November in New York and I had not seen the sun at all this season. Because I didn’t know how to articulate what I felt then—which was both understanding and vehement disagreement—I smiled as I often did when recoiling from the sting of an unexpected blow.

The truth is, she wasn’t wrong for insisting that being a fair-skinned minority in America does equate to privilege. The privilege of opportunity, praise. The privilege of being seen. Her comment made me recall the season of my youth when all I’d wanted was the privilege of being perceived as white: a mark that I had successfully assimilated, disguised what made me different, and this is where the poem starts.

Here, Medusa is a reflection of the speaker’s younger self—a girl who once felt she was abominable, ugly, othered. In a strange way, the girl at the party’s affirmation that I, with my curls concealed, could moonlight as a gringa, gave me a quick hit of dopamine followed by an immediate pang of disgust. After receiving the validation I’d been searching for for so much of my life, I felt my brown body being erased and realized I did not like being seen wrongly, for something I was not.

Maybe Medusa felt this too—having once been a woman before she was raped and killed by the gods, her hair replaced by the heads of snakes. When the speaker of the poem reaches out to Athena and asks, “In how many languages will I have to apologize for someone else’s misinterpretation?” what she really wants to know is how she can be held responsible for the perception of others and the subsequent damage caused by their gaze. Just look at how Medusa’s life unfolds—the gods are found blameless while she’s punished for the rest of eternity, made monster in her ruining. In her story, the cruelty of her punishment doesn’t lie in her banishment, or even in her beheading, but in the simple fact that she can never be truly seen or known by anyone ever again as a result of being raped.

As I end the poem, I try to present a moment in which the speaker reveals and celebrates her brown body, by giving herself and the reader a chance to see all of her without penalty. No longer is she afraid of what they might discover, understanding finally that the consequences of misunderstanding are not her fault, but “simply the reflection / of their own dark staring back at them.” What the speaker comes to realize by the end of this poem is that it is not so important for her to decide how she will face the world as it is for the reader to make a moral choice: Who is responsible for the villainizing of women we are taught to see as other and fear? Said another way— in the history we are living through today, the history we have always faced, who deserves the right to be seen? Who is truly god, monster?