First Loves

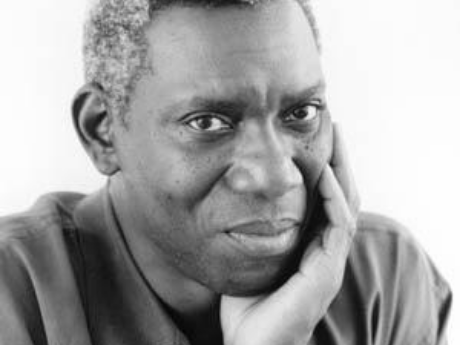

Yusef Komunyakaa: First Loves

Annabel Lee

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee—

With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in Heaven,

Went envying her and me—

Yes!—that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud by night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

Perhaps it was how the poem's title first wedded my tongue, without any hesitation, conscious negotiation, or humbug: "Annabel Lee." It seemed as if some deep part of myself already knew the rhythm and emotion of this name—a Southernness in its music. But Edgar Allan Poe's "Annabel Lee" also ushered in a disquieting mystery and the strange feeling of eavesdropping on something almost taboo.

At nine years old, I knew next to nothing about this kind of love, although I had been lightly touched by an element of it in the blues that drifted out of the radios in our kitchen and living room. To know this great longing through words made me tremble inside my skin, and I believe it helped me traverse some new territory in my imagination. "Annabel Lee" was familiar and distant, ethereal and knowable, and not quite flesh: Had she wandered from across the tracks to my forbidden "neck of the woods," and why did I sense her with such imaginative authority? She was there and not there. In this sense, I feel that I grasped Poe's Gothicness. But I had also been transported in my psyche to immediate possibility: my Annabel Lee became a honey-colored Goldie Rae Magee. And I can still half hear my nine-year-old voice saying, "She was a child and I was a child, / In this kingdom by the sea...."

At the time, of course, when I memorized this first poem, I couldn't have been conscious that this otherworldly love between two children embodied Poe's recurring theme of Death in Love. Also, I don't believe I was fully aware of the possible critique of class in the poem. Now, "So that her highborn kinsmen came" seems more about authorial reality than an excursion into gothic imagination. And there is another moment in the poem that challenged the regional orthodoxy I grew up with: "And neither the angels in Heaven above / Nor the demons down under the sea, / Can ever dissever my soul from the soul...." Within the psychological iconography in which I was born and raised in rural Louisiana, angels and demons were more than powerful; there wasn't any human emotion that could challenge them or diminish their powers.

It should be no surprise that James Weldon Johnson's "The Creation" would be the second poem I memorized. At Sweet Beulah Baptist Church, Reverend Duncan could really preach—no doubt about that. But there is something in "The Creation" that transported me beyond my imagination. This lyrical narrative has a fiery precision that pulled me into its sway: I felt lost and found through the poem's music. Yes, in many ways, Duncan's image of God parallels Johnson's: "And God walked, and where He trod / His footsteps hollowed the valleys out / And bulged the mountains up." This majestic, brute force seems like a forerunner of some god of high-tech thunder—a bionic godhead. But there was also something different about Johnson's God: "This Great God, / Like a mammy bending over her baby, / Kneeled down in the dust / Toiling over a lump of clay...." In retrospect, now I know it had to have been the cinematic Southernness of this image that connected me emotionally to Johnson's poem. I feel that I knew this surreal figuration: it seemed to weigh flesh against all the abstraction and hyperbole, alongside an exhortation and metaphoric playfulness.

I am thankful that these two poems led me to other more challenging ones. My mind and body can almost recall (if not relive) that moment in the urgency of language when I discovered "Annabel Lee" and "The Creation," and it seems like this must be what happens when one falls in love the first and last time.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 1998.