Old School

On Sir Thomas Wyatt’s “Epigram XLI”

I first became familiar with Sir Thomas Wyatt's "Epigram XLI" from Jacqueline Osherow's essay on ottava rima in An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art (ed. Annie Finch & Kathrine Varnes, U of Michigan P). I have been using this book for the last several years as a text for my Craft of Poetry course for the Whidbey Writers Workshop MFA Program.

Prior to that, I was aware only that Wyatt (1503-1542) was the English courtier whose chief claim to poetic fame was to introduce the sonnet to English. Like Chaucer, a poet-diplomat of two centuries earlier, Wyatt was sent to Italy on royal ambassadorial missions—in his case, in the service of King Henry VIII. There Wyatt encountered the sonnet in the form perfected by Chaucer's contemporary Petrarch: 11-syllable hendecasyllabics, with rhyme patterns that organize the lines into octave and sestet. Fluent in Italian, Wyatt first encountered il sonetto in Italia in the 1530's. He read, translated, and brought this exotic "little song" back to Tudor England, whereupon it became the most studied, appreciated, and practiced form in the English language.

As a poet who has traveled much and translated throughout her career, I could relate to students how Wyatt's translations of Petrarch's sonnets, and his experiments in writing his own sonnets in English, helped transform this little song to a form more suited to the English language's accentual stresses and poverty of rhyme (iambic pentameter lines, organized as three cross-rhymed quatrains and a "heroic" rhyming couplet to conclude). I have had students try to imagine the circle of literate noblemen and women of the Tudor court and the professions in the City of London practicing this poetic form. They were lovers of wit and verbal display, hand-writing their poetic efforts or having them printed up in small chapbooks—all in the liberating vulgate of English, their native tongue, as contrasted with the rigidified Latin of the doctors of the Church. The sonnet was a form that in its English variations became the crowning poetic form practiced by the most renowned poet and writer in our language, "the Bard": William Shakespeare.

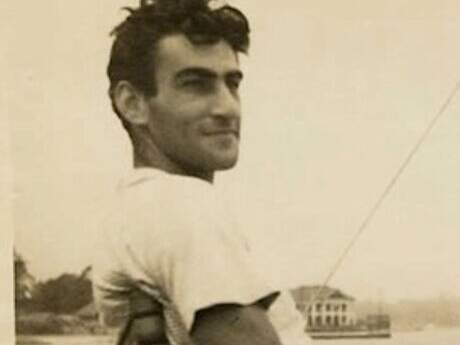

And, of course, the sonnet's traditional theme—romantic love in all its virtues, vices, and vicissitudes—comes into play here. One of the most intriguing aspects of Thomas Wyatt's life was his rumored affair, or at least romantic fascination, with Anne Boleyn, King Henry's second wife and the mother of the future Queen Elizabeth! As a high-level diplomat, Wyatt was a public figure—his portrait was done by Hans Holbein the Younger, painter to the Tudor royals and nobility—so he had social interactions with the royal family, and had apparently met Boleyn in France in the 1520s, before she attracted the attentions of the king. We will never know what transpired between them, but we do know that like some other high-born men associated by political or family alliances with Queen Anne, Wyatt was imprisoned for a time in the Tower of London after the Queen fell from King Henry's favor. Unlike these other gentlemen, though, who were executed around the same time that Anne was beheaded, Wyatt was eventually freed with his head intact!

Sir Thomas was indeed a man of parts who assayed many poetic forms other than the sonnet, among them the ottava rima, another form derived from Italian, composed in stanzas of eight lines rhyming abababcc. "Epigram XLI" is a stand-alone stanza in this form—

She sat and sewed that hath done me the wrong

Whereof I plain and have done many a day,

And whilst she heard my plaint in piteous song

Wished my heart the sampler as it lay.

The blind master I have served so long,

Grudging to hear that he did hear her say,

Made her own weapon do her finger bleed

To feel if pricking were so good indeed.

c. 1542

"Epigram XLI" is a complex piece of wit—at least for our era, which tends to favor short, direct, syntactically simple, punchy sentences, to create what we regard as maximum impact. The syntactical complexity, the interruptive clauses of the periodic sentences that make up this poem, help to create not immediate, maximum impact—but a gradual accretion of impact, an affect that builds more gradually by indirection . . . and to my mind, endures longer. But first we have to sort out the complex sentence structure and the archaic language with its word play.

The control of diction and sentence structure demanded by adherence to the form makes the sly wit of the poem even more effective. And the wit is not only sly but bawdy—in those days poets had to speak indirectly in order to get suggestive poems past the censors: the offices where they had to register their work if they wanted it published (printed for public sale) beyond circulating it privately in manuscript copies among friends and associates.

I like the dramatic scenario here—the poet relating how his lady love has refused to respond to his "plaints," while she sat sewing, seemingly indifferent to him, quite able to resist him. What would have been a gesture of wit in the 16th century, though, sounds rather melodramatic and self-pitying today. The speaker imagines that the lady wishes his heart were the sampler she is piercing over and over with her embroidery needle, so that she would be stabbing him in the heart, not just metaphorically but literally.

In this dramatic situation, could "she" be a figure for the unattainable Anne Boleyn—who could in no way have carried on an affair once the King set his sights and ambitions upon her; and moved heaven, earth, the Pope, and canon law to divorce his first wife in order to marry Anne and make her Queen. (She would lose her head despite her protestations of fidelity, once she had borne a live daughter, miscarried a few male babies, and lost favor with Henry, who turned his attentions toward Jane Seymour.)

Actually, the poet-speaker claims triumph here, I think. He asserts, gloating, that his "blind master"—lust, or perhaps the very organ of male lust—has made this heartless lady prick her finger with her own needle. The blood drawn by this minor accident is a metaphor for the bleeding of a woman when she loses her virginity and is "deflowered": the assumed goal of the courting male poet. Even today we know what "pricking" means, in the suggestive metaphorical sense—today we use the noun form for the male member and for the gents who do their thinking with it! But back then the verb form was one of the more polite suggestive terms. And this woman, who has wronged the speaker by refusing to do it in the literal sense, gets a taste of it when her own "weapon" pricks her finger and makes it bleed. The poet-speaker is grasping at straws to claim some sort of triumph here—that somehow she has been conquered metaphorically by the needle's pricking her finger and making it bleed.

All this in eight lines, rhyming abababcc: concision and density of language! It certainly sets a standard of formal attainment and wit for the rest of us. That said, I don't entirely believe the tone of "plaint" here, to regard the lady's unresponsiveness as a "wrong" done to the speaker. The poet is writing with the courtly and romantic conventions of his day, so I forgive him the poem's unwitting, though witty, sexism. In the tradition of the Muse Strikes Back, though, I would like to make my own "plaint" in a reply to the speaker of this epigram, perhaps in the voice of the sewing lady—in the same form, a single ottava rima stanza.