On Poetry

Carl Phillips on Audre Lorde

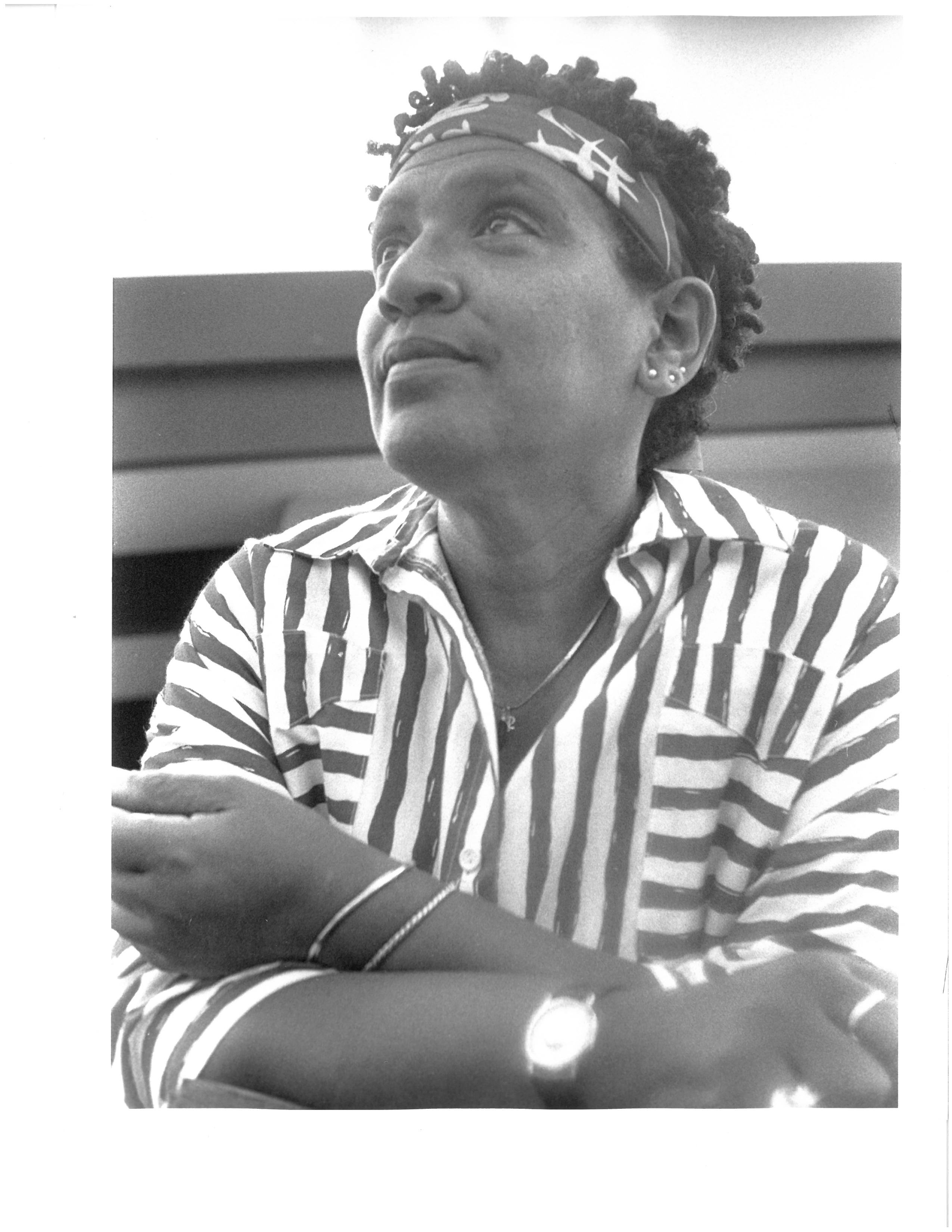

In May of 1970, Audre Lorde visited Fassett Studio to record a reading for Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room.

The Fonograf Editions 12″ LP of this reading includes a 12-page liner notes booklet with poems by Fred Moten and Pamela Sneed; and essays by Tongo Eisen-Martin, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Carl Phillips, whose essay is reprinted here.

Carl Phillips on Audre Lorde

Until listening to this recording, I’d never heard Audre Lorde’s speaking voice. I don’t think I had any particular preconceptions of how she’d sound. I just hoped she wouldn’t disappoint me the way so many of my poetry idols have, once I’ve heard them read; it’s amazing how many poets seem unable to read their own work well, by which I mean with a confidence that doesn’t shun humility, and with a persuasiveness that avoids sounding pedantic.

Confident and persuasive from the start, Lorde doesn’t disappoint. What I was most immediately struck by, though, was the exactness of phrasing Lorde gives to each word, something that goes beyond mere enunciation – this reading is like a master class in elocution. And as it turns out, this isn’t just a style that Lorde adopts when reading her poems; she sounds the same when speaking casually in between the poems. I don’t want to make too much of what quite likely was just how Lorde grew up speaking, instinctively. But in the context of this reading, and of Lorde’s body of work, I hear a very deliberate insistence on precision – precision as the main weapon with which to negotiate a world where the stakes – politically, bodily, in love and in war – are always decisively high. Michael Palmer has spoken of words as a sacrament to be handled accordingly with great care. For Lorde, it’s as if great care were necessary, yes, but more because, for her, language is not so much sacred as explosive: I am making something dangerous here, Lorde seems to say, I could do great damage with what I make; I could destroy myself, if careless, in the course of making.

Hence, a slowness, a deliberateness to the delivery of the poems aloud. The danger of language, Lorde knows well, is that it can so easily mislead or flat-out deceive. We’re constantly moving through what (in “Song”) she calls a “forest of falsehoods,” and the medium by which those falsehoods get deployed is language itself, words, and what they can be made to stand for. Lorde shows how this works, racially, in her poem “The American Cancer Society Or There Is More Than One Way to Skin a Coon,” in which she sees the “seductive and reluctant admission” that Black people are in fact human as evidence of how the “American cancer” (note how she leaves out “Society,” no longer speaking of the organization specifically but of the more general American condition) destroys by “dump[ing] its symbols onto Black People/Convincing proof that those symbols are now useless/And far more lethal than emphysema.”

It seems another point of precision, to follow this poem with “Sewerplant Grows in Harlem Or I’m a Stranger Here Myself When Does the Next Swan Leave,” which Lorde introduces by giving some context: a garbage disposal plant originally to be built in mid-town Manhattan has been relocated to the Harlem neighborhood where Lorde herself lives. The city council, she says, offered no explanation. But even in the withholding of language – of explanation – there’s an implied message. What does it say, without saying?”

“How easy it is to take the form for substance,” Lorde says in her remarks just before her reading of “Naturally,” going on to say that “it’s an error Black people can’t afford to make now, today – or ever, I think.” In the context of language, it becomes all the more crucial to distinguish what’s said from what’s meant, and not to confuse silence with emptiness: silence, too, often means a great deal, the silence of the city council being one very loud example. The context isn’t limited, though, to the intersections of marketing, corporate greed and indifference, race, and societal restiveness. Often, for Lorde, the context is human intimacy, where again language often suggests or signifies one thing and can mean another. In “Summer Oracle,” after speaking of a magician’s cloak “covered with signs of destructions and birth,” Lorde addresses an apparent beloved, describes their body as “close, hard, essential, under its cloak of lies.”

How to get at what’s essential, at the essence – of ourselves, of those whom we love, of a society that seems reluctant, at best, to include all of us? “I am trying to tell this without art or embellishment,” Lorde says in “Blood Birth.” The poems display great artistry, of course. But it’s also the case that, as with how she reads, what for Lorde defines artistry is a spareness, an exactness, an avoidance of overcrowding a poem with images; Lorde knows the single right image is much more powerful than several less carefully chosen ones. She also understands the potential (the tendency?) of images, when brought together, to work in unison as camouflage – form that can distract from the substance behind it. It’s an odd conundrum. The work of a poet is to gather words and imagery together to convey a particular meaning or set of meanings. But the imperative that goes with that is to recognize how words, like imagery, when brought together can deceive us. And Lorde suggests, even in how she’s arranged her set of poems for this recording, that this deception has the potential to occur in contexts that straddle public and private. It seems very purposeful how, right after a sequence of overtly ‘political’ poems – “The American Cancer Society…,” “Sewerplant Grows in Harlem…,” and “A Ballad of Black Childhood” – Lorde casually announces that the next three poems “are love poems,” which are then followed by “Conversations in Crisis,” where she could as easily be addressing a lover or a corporation when she distinguishes her addressee’s words from “the false heat in the voice,” a distinction that alerts her to the power of words to deceive: this is what marketing knows, this is what those whom we trust most intimately also know – what we ourselves know. Who of us hasn’t betrayed someone, even if incidentally, even if it’s ourselves we betrayed?

“Take my word for jewel” – that’s how Lorde, aloud and on the page, delivers each word, with a consciousness of any word’s value, and of its powers both to destroy and to illuminate. “Some words/Bedevil me.” Love is a word, too:

Love is a word another kind of open –

As a diamond comes into a knot of flame

I am black because I come from the earth’s inside

Take my word for jewel in your open light.

For me, these lines say everything about Lorde’s gift to American letters, namely, her commitment to the poet’s responsibility to look honestly, truthfully, at the worlds around and within us, to find the essence of human interiority – “the total black, being spoken/From the earth’s inside” – and to understand it through the clarity of open light, “another kind of open.” We have everything to lose – and, being mortal, we must inevitably eventually lose it. All the more reason to take the full measure and value of what we have – this life – and to honor it by giving voice to each flashing aspect of it, word by word, jewel by jewel. Precision in this context becomes more than strategy. It’s an act of rescue – a choice. It’s an act of love.