Q & A: American Poetry

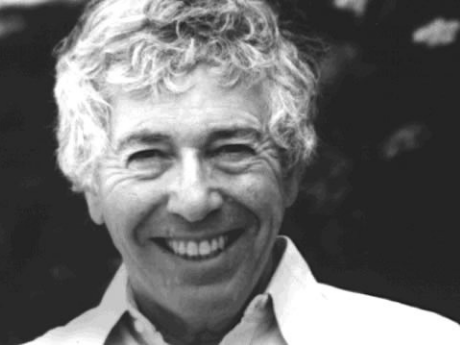

Q & A American Poetry: Kenneth Koch

Ice is like prose; fire is like poetry. But neither melts nor goes out. Ideally (or unideally, some would say) they generally ignore each other's existence.

Rhyme is like a ball that bounces not in the same place but at least in another place where it can bounce.

Poets who write every day also write every year, which is the important thing for poetry.

The poet is the unacknowledged impersonator of the greatest unborn actors of his time.

The Romantic movement left, when it departed, a tremendous gap in poetry which could be filled by criticism and by literary theory but which would be better left alone.

Rome inspired architects and sculptors and painters; the Lake Country inspired poets. Milton inspired Keats. Perugino taught Raphael. Blake gave ideas to Yeats. Sciascia read Chroniques italiennes once every year. Byron learned something from Pope. Even the most unsentimental person is glad to see his home country again.

A tapestry is not like a lot of little poems woven together but like one big poem being taken apart.

Starting off as an Irish poet, one has a temperamental and geographical advantage. Starting off as a French poet, one incites overwhelming curiosity as to what can be done. Starting off as an American poet, one begins to develop a kind of self-consciousness that may quickly lead to genius or to nothing.

Would that he had blotted a thousand! "perfection" is wonderful in poetry but Shakespeare is good enough— one reads on!

There are three Testaments and one is illegible.

The iris is a flower that is part meridian, a ghost come bearing you a villanelle.

What is the matter with having a subject? Wittgenstein says, "There are no subjects in the world; a subject is a limitation of the world." In fact our subject is all around us like a mail-order winter that we carelessly sent in a request for when it seemed it would always be spring.

Eve was the first animal. Therefore she could not have been Eve, and Adam could not have written poetry. Adam could not write poetry unless there was a human Eve. Thousands of years later, there was: Eve de Montmorency. But she didn't encourage the production of poetry. She said I'll kill anyone who writes me a poem. I like life to be real! Inspired all the same, a few poets began writing "free verse" (and it was pretty good) which she was unable to recognize as poetry. Meanwhile, back in the Garden of Eden, Eve woke up. She was a fox no more, but a woman, and a ravishing one! Adam saw her and became terribly excited. Without willing to or wishing to at all (for who could know the consequences?) he fell to one knee, held out his hands and recited: Roses are red, violets are blue. Yes, what's the rest? Eve said. I don't know Adam said. I'm not yet fully a poet. That's as far as I've got. So far, so good, Eve said, and she loved him with a new ardency that night. From their union were born Abel and Cain, who represented two dissenting schools of criticism: Abel, the "inspirational let-yourself-go, just SAY it, let it all hang out, or blossom! Lyrical School"; Cain, the party of more rigorously crafted delight, a sylvan Valery: l'inspiration n'est pour rien— le travail, en poesie, est tout! They fought and killed eachother many times, while Eve brought forth more children in sorrow, and Adam, his body aching, tilled the land.

Once I taught polar bears to write poetry. After class each week (it was once a week) I came home to bed. The work was extremely tiring. The bears tried to maul me and for months refused to write a single word. If refused is the right term to use for creatures who had no idea what I was doing and what I wanted them to do. One day, however, it was in early April, when the snow had begun to melt and the cities were full of bright visions on window glass, the bears grew quieter and I believed that I had begun to get through to them. One female bear came up to me and placed her left paw on top of my head. Her mouth was open and her very red tongue was hanging out. I realized that she, and the other bears, must be thirsty, so I procured for them several barrels of water. They drank it thirstily and looked up at me from time to time to gratefully but even then they wrote no poems. They never did write a word. Still I don't think this teaching was a waste of time, and I'm planning on continuing it if I have the necessary strength. For hard and exhausting it is to attempt something one knows it is impossible to do— but what if one day those bears actually started to write? I think would all put down our Stefan George and our Yeats and pay attention! What wonders might be disclosed! What dreams of bears!

Reading is done in the immediate past, writing in the immediate future.

The world never tires of bad poetry, and for this reason we have come to this garden, which is in another world.

Published 1999.