Red, White, & Blue

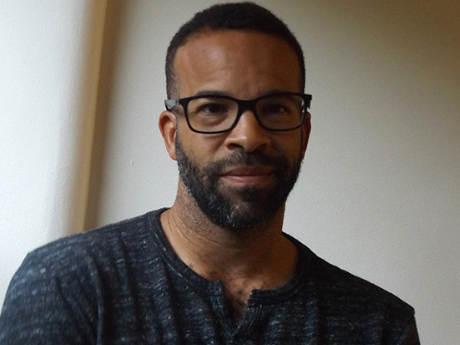

Douglas Kearney

Do you value the examination of the political in poetry? If so, what experience(s) taught you its importance?

I value examination itself in poetry. Examination of the range of human experiences as a means to reckon with the world we're in, the world we're making. The political is a part of this range and I think poetry is well-equipped to deal with examining questions about the desire for power, grappling with the dangers of that desire, the ways we deal with those we consider of lesser, greater and equal power as ourselves. There are of course, as Tracy K. Smith once said, things a vote can do that a poem cannot and vice versa. Things a petition can do, a bill can do. But in my experience as a writer and reader, poetry is excellent for examining will and want. These seem to me engines of the political.

If you write about politics frequently, what issues, difficulties, advantages and disadvantages do you negotiate? Which poets do you draw on when conducting such negotiations?

I write about violence, though rarely on the scale of war. I write about race quite frequently and how we perceive race is entangled with the political, of course. When I write about race, I am interested in how complex and complicated our attitudes around it can be. In many ways, racism, say, is ridiculous. But when something ridiculous has the power to destroy lives, it becomes horrifying, grotesque. I try to make my way to the crossroads of these conflicting tenors—humor and terror, thoughtlessness and obsession. I am often angry about these things, but witnessing a black man being angry is often cathartic for audiences—like riding a scary roller coaster or seeing a monster movie. I think it allows people to feel that everything is where it belongs. The layering of conflicting emotions keeps folks more off-balance. It's unsettling. This, I think, is important in the project of the political poem, at least as I see it.

I'd be at a disadvantage if I tried to see this engagement with understanding the capacity for human kindness, cruelty, endurance and frailty at the vector of race as something somehow exclusively external to my own navigation through the world. A kind of extracurricular activity to be addressed when I got done with the business of being a Universal Human™. I see it as something that doesn't divorce or disqualify me from my humanity, rather it is a particular subjectivity that—heh—colors my interactions with the globe-full of other particular subjectivities.

I can only imagine that my way of seeing from myself into the world back at myself is the reason for, not the byproduct of my interest in writing poetry that overtly takes race in hand. So I can't say it's an advantage.

I look to Harryette Mullen whose use of black signifying practices insists on the complexities of looking, being looked at, naming, and being called even when she isn't talking about black stuff directly. I value that mess. In her debut, Hemming the Water, Yona Harvey writes from the ominous and weird worldview of what seems to me the same folklore that holds the devil as an abstraction and a man loose in the woods or the brownstones. Fred Moten, the Black Took Collective, Amaud Jamaul Johnson's newest manuscript, Nick Demske's ODB poems—these are all bright lights for me.

What 'responsibility' does an artist have to artistically engage his or her own politic?

I teach at California Institute of the Arts and I have come to say that artists have the responsibility to make art—and then they have the responsibility to stand up next to that art and be accountable for what they are telling/showing the rest of us. That accountability is more generative when one has critically engaged her own artwork and its place in a larger discourse which has a place in a larger social context which has its place in a certain history. How the artist seeks to position the work in this trajectory is often at least incidentally political. It's difficult to get outside of that because making art and making that art public is a bid for eyes, ears, hands and often, physical space. These have to do with access, which has to do with power, which has to do with politics.

I will add that art often comes from questions. Not just answers. From process. I value the artist who first questions herself. I find that process to be most compelling. That art teaches me how to fish. The art that already knows it's right tries to give me a fish. Occasionally, it's nice to get a free fish. One could call it a gift. But I'd like to know a bit more abut catching my own. Sometimes those free fish ain't cooked right.

In 2008, Horace Engdahl, the secretary of the Nobel prize jury, wagged his finger at American writing saying that "[American writers] don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature. […] That ignorance is restraining." What do you think? How have recent American poets engaged with or neglected the so-called 'big dialogue' of literature? Is this 'big dialogue' a political one?

So many folks have written eloquent responses to this assertion that I'll just say: It's where you look, isn't it? Where you expect to find writing engaging the big dialogue and where that writing actually lives are not always the same place, are they? What must you do then but look where you haven't already looked?

Is there room for romantic or rugged individualism in political poetry (as opposed to a capacious perspective of Whitman or other past poets)? If so, where is its place?

Ideas are important. I'm troubled by "where is its place"—my answer to that would be dictated strictly by my own prejudices which are wholly inadequate for such a decision. I'm not being humble. Perhaps EVERY ONE of us is wholly inadequate to dictate the place of an idea. So I'll signify: its place would most likely be in a political poem of romantic or rugged individualism. Not even necessarily a good poem of that sort. But I'd look there first and skip the other places (here, I'm roughly quoting a cartoon duck named "Quack").

Where do you draw the line between poetry and propaganda? What is the purpose of such a line? Should today's poet be concerned with editorial censorship?

Ha! When I agree with the poem, it's strong political poetry. When I disagree, it's propaganda! Isn't that it? But, I think propaganda is less likely to question its message without using straw men. There is likely also a "call to act" outside the realm of reading. This call reinforces the thrust of the unquestioned message. Of course, propaganda is often transparently metonymous with an actual political body. In these ways, propaganda is essentially an advertisement. It may have dynamic, unforgettable language and artfully rendered images, but it's advertising. I used to be an advertising copywriter, so perhaps this view is too idiosyncratic.

If one draws a line, I think that person is making a literary judgment which may not mean much to an actual propagandist. There is also the possibility that one draws the line to marginalize another writer, a stunningly political act. Another reason to draw the line is to cross it.

"Should today's poet be concerned with editorial censorship?" Now I'm having fun quibbling with the questions. I think EDITORS should be concerned with Editorial Censorship. Poets should write. And, if they face censorship, there are a number of other ways to disseminate work beyond edited journals.

What are your thoughts on shifts in the state of the political voice in contemporary poetry, from the early modernist to the beat poets and black arts movement, to today? Where are we now? Where are we going?

I think it shifts to meet a will or a want. It isn't always the will or want of the majority of folks, but it is someone's. In contexts where poetry is a valued component of what's considered an informed, dynamic worldview, that expression of desire may shape those who attend to it and some of those folks may end up in positions of power. Poetry's influence is neither intrinsically bad nor good, so this access to a resonant (or seductive) will/want is of ambivalent matter.

As far as where we're going, I've been recalcitrant at earlier points in this questionnaire, so I'll play along now. From my standpoint, I think there's a desire to be "post- " (race, gender, human) and I'm distrustful of a drive to invalidate certain kinds of dialogues right when so many interesting people are starting to speak more freely. It's like there's something somebody doesn't want to talk about and so wants to change the subject for everybody in the room. What is that somebody hiding? Of course, if this is just time rolling on, then perhaps my suspicion is just a way of rationalizing my desire to hold on to something becoming obsolete. But as a high school senior in 1992, I drove a car with an 8-track in it. I know from obsolescence, and this feels different.

No. It feels like a crime scene and someone with something that looks kind of like a badge is saying: "Move along, folks. Nothing to see here." But there is, isn't there? Right past that tape. Right under that sheet.

* * *

Poet/performer/librettistDouglas Kearney's second manuscript, The Black Automaton, was chosen by Catherine Wagner for the National Poetry Series and published by Fence Books in 2009. His newest chapbook, SkinMag (A5/Deadly Chaps) is now available. He lives with his family in California's Santa Clarita Valley. He teaches at CalArts and Antioch.

Published September 2012.