Stopping By

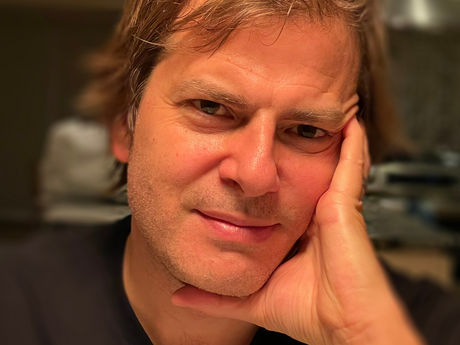

Stopping by with Andy Hunter

Andy Hunter is the founder of Bookshop.org, a bookselling platform that helps local, independent bookstores compete with Amazon for online sales. He is also the co-creator and publisher of the website Literary Hub, the co-founder and Chairman of Electric Literature, and a writer and editor. His focus is helping books remain a vital part of our culture in the digital age.

What is the last thing that moved you?

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut is a work of literary art, and an exploration of humanity’s attempts to grasp the incomprehensible infinite: the fragments and glimpses of our underlying reality we can achieve through mathematics and physics. I absolutely loved this book and wished I could read a dozen more books like it—but unfortunately, I don’t think there are any other books like it.

What is a piece of art that changed or greatly influenced your life?

This is just one instance of many, but for whatever reason it’s what occurs to me now: When I was really young, maybe twelve, I couldn’t sleep. I was fiddling with my bedside clock radio, and Laurie Anderson’s “Oh Superman” came on. It’s hard to explain the effect it had on me. I was a suburban kid with no knowledge of art or literature beyond having read Bridge to Terabithia and my parents listening to The Beatles. When I heard Laurie Anderson’s singing, it provoked a strong existential feeling in me. I somehow understood in that moment that there were artists out there in the world, distant through the darkness over the radio late at night, making strange and mysterious art. I grabbed a tape recorder and captured the end of the song. I would listen to the tape sometimes, but it was years before I found out what it was. None of my friends understood why I cared about this unusual song that was played on the radio late one night, but for me it was a clue in a mystery—that mystery was ultimately about how art could affect my life and shape my understanding of the world.

What is your first memory of poetry?

Beyond rhyming couplets taught in school that didn’t matter much to me, the first poetry book that I remember being surprised by was by Anne Sexton; my mom had the book. I picked it up out of boredom when I was still pretty young, and discovered it was transgressive and intimate. I realized that some moms had more going on than I had thought. But when I was young, poetry was mostly lyrics to the songs I loved.

How have the last years changed you, and what is something that you will take with you into a post-pandemic world?

What I’ve felt most profoundly is how much meaning is dependent on the presence of other people. There was a point in the pandemic when everything started to feel truly virtual, in the same sense that videogames are virtual—diverting but ultimately meaningless. The “literary world,” however you might define it, felt real and full of gravitas to me when I was living and working in New York City, creating publications, writing, editing, meeting with writers, visiting publishers, getting lunch or drinks, attending award ceremonies and parties, arguing about books in bars, all of that. But eighteen months into the pandemic, watching a livestream of the National Book Awards, I felt like, “Does any of this matter? Did it ever matter?” Of course, I was fighting off depression by that point, but it’s also true that when all of your relationships are mediated through a screen, you cease to be alive in the same way. I’ve found that now that I see people again, I care more, again. By the way, that is not a call for returning to work in the office. Bookshop.org, Literary Hub, and Electric Literature are all fully remote! It’s just an acknowledgement that we need to engage all our senses, create the richness of experience, and we find meaning in our lives through our relationships with others.

Who or what is your greatest creative influence?

The answer changes as I move through life. Right now, I would say Beckett. But at 40 it was Thomas Bernhard, at 35 it might have been Virginia Woolf or James Baldwin; at 24 it was Dostoevsky, and so on, all the way back to Maurice Sendak, probably.

If you were to choose one poem or text to inscribe in a public place right now, what would that be? And where would you place it?

That’s an interesting question. Why not engrave "A Litany for Survival" by Audre Lorde on Wall Street’s “Charging Bull?” Lots of people would read it. It would give them something to think about.

What do you see as the role of art in public life at this moment in time?

I think it’s the same as any other moment in time: art helps us see truth—interior truths, social truths, and political truths. It moves us. It connects us to each other and our past. Art makes us laugh, dance, cry; it makes us mad. It sometimes shocks us and sometimes soothes us. Art is something that, in hard times, some people think of as superfluous and indulgent–but it helps us get through hard times, and helps people remember them.

What do you want people to take away from your work?

Well, most of my work is supporting and advocating for writers, books, and book people. What I want is for literature and poetry to continue to be an essential part of our culture.

Are you working on anything right now that you can tell us about?

I’m writing a story about a man with a magic clock that he can wind backwards to go back in time, but causes him to lose all his memories of the future. He’s aware he has gone back, presumably because he had messed something up and wanted another chance. But he has no idea what he ended up regretting or how to remedy it. Eventually, he wears out the clock.

What are you hopeful for?

I’m hopeful that life adapts and though it often goes in a bad direction, it seems to correct course eventually. Our bodies learn to fight off a virus; a people learn to fight off a tyranny. I’m hopeful because my kids and their friends are smarter and wiser than me and my friends were at their age. I wish they didn’t need to be.