Stopping By

Stopping by with Raven Leilani

During this extraordinary moment—of both pause and activism—we asked writers, musicians, curators, and innovators to reflect on the power and memory of language, shared spaces, and this moment in time.

Raven Leilani’s debut novel, Luster, was published this summer by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Her work has been published in Granta, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Yale Review, Conjunctions, The Cut, and New England Review.

What is the last thing that moved you?

This year has been hard and strange, and it’s been difficult to sustain attention long enough to retain anything, but here are a few poems that knocked me over: “Rose” by Danez Smith, “After Abolition” by Kyle Carrero Lopez, “Hades” by Aria Aber, “My Phone Autocorrects ‘Nigga’ to ‘Night’” by Karisma Price, “Versal” by Francis J Harris, “All They Want Is My Money My Pussy My Blood” by Morgan Parker, “Attempt To Commit A Suicide To Memory” by Janelle Tan, “They’ll Ask You Where It Hurts The Most” by Kwame Opoku-Duku, “My Mother Is A Shot” by Omotara James, “Strawberries” by Angela F. Qian, “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin [‘Probably twilight makes blackness dangerous’]” by Terrance Hayes, “And Who Would You Prefer Tell The Story “by Sasha Debevec-Mckenney, “you’re welcome” by Bernard Ferguson, “There They Are” by JinJin Xu, and “Gospel Of The Misunderstood” by Safiya Sinclair.

What is a piece of art that changed your life?

Monet’s Haystacks series (a series of paintings of haystacks) changed how I felt about the value of study, or repetition. I am generally drawn to bodies, but I love this series for how it captures late afternoon light, or how its fluctuations influence form. I love the warmth of the palette but also the idea of treating a mundane facet of the natural world seriously, as a thing that is worth close observation and reiteration.

What is a piece of art everyone should encounter?

I think everyone should watch Yi Yi, a film by Edward Yang. It is a gorgeous multigenerational drama that zeroes in on the small, devastating moments that are suffered in childhood, or during stages of development where your personhood is not yet treated with seriousness. The lives of young people are rendered with dignity, but also with incredible candor—how it feels to grieve, to want to be desired, to commit those first tentative sins. I love the way people talk to each other in this film. The dialogue is relaxed and organic, and being a viewer feels at times like being a voyeur, which I love.

What is your first memory of poetry?

I found a copy of Robert Lowell’s Collected Poems in my middle school library, and it was the first time I ever encountered what at the time felt like dense, figurative language. I didn’t have the vocabulary then for what I liked about it, but now I think it forced me to read closely, as many of the references were unfamiliar to me. The language felt beautiful, but I only rarely found pockets in the work that I completely understood. But those moments of revelation kept me going. It felt like a challenge. It was the first time I considered the possibility that there might be other rhetorical options beyond the most obvious or transparent expression of a thing. After that book, I wrote the most terrible, opaque poetry, but it animated me.

The pandemic has emptied many public spaces (libraries, concert halls, museums, parks, transit systems, etc.). What space—and community—do you miss the most?

I really miss museums, even the part of visiting a museum that makes it an ordeal—the density of the crowd, especially around a big piece, the way that sometimes tips you off before you’re even in the room. That always feels so earnest to me, the decision to go out and fill yourself up with art.

Public space is rife with words—signs, logos, advertisements. If you were to choose one poem or text to inscribe in a public place right now, what would that be? And where would you place it?

I’d place Lucille Clifton’s “won’t you celebrate with me” along the 87 Interstate. Clifton was from upstate New York, and so am I, so I’ve driven that route often, and it is a beautiful stretch of road where I think a lot of people would be able to encounter it.

Have you thought differently about the role and power of language and art in the wake of murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and the wide-spread protests?

I have been thinking about the role of language specifically around how protests—and how the people who are doing the protesting—are framed. The way we use passive language to talk about the perpetrators of brutal, state-sanctioned violence and active language to characterize the human responses of the people who are subject to it. The tacit condemnation of humanity in the face of a system which dehumanizes with impunity. Language isn’t neutral. A system which enables its public servants to murder black people at home isn’t neutral. So to strive for neutrality in the reporting of these stories is a deliberate choice to look away from what is plain.

Have you created something during the lockdown, or are you working on anything now?

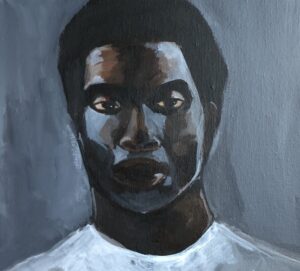

Since the pandemic started, I’ve been less able to write, but painting is coming more easily. I’m writing a few shorter pieces, which are easier to commit to because the finish line is closer, but otherwise, I’m painting and trying to take in as much as I can.