Stopping By

Stopping by with Susan Barba

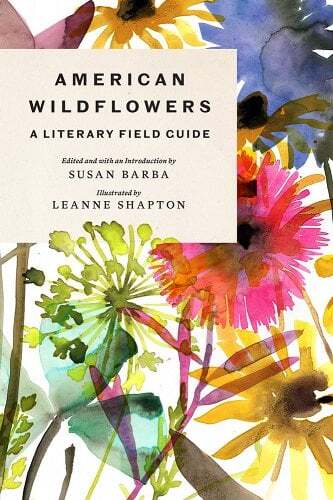

Susan Barba is the editor of the new illustrated poetry anthology, American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guild. She is the author of the poetry collections Fair Sun (2017) and geode (2020), a finalist for the New England Book Awards and the Massachusetts Book Award. Her poems have appeared in the New York Review of Books, Poetry, the New Republic, and elsewhere, and they have been translated into Swedish, German, Romanian, and Armenian. She works as an editor at New York Review Books and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

What is the last thing that moved you?

3 Summers by Lisa Robertson. The poems, the art by Hadley + Maxwell, the design by Alana Wilcox, even the colophon amazes: “Printed and bound at the old Coach House on bpNichol Lane in Toronto, Ontario, on Zephyr Antique Laid paper, which was manufactured, acid-free, in Saint-Jérôme, Quebec, from second-growth forests. This book was printed with vegetable-based ink on a 1965 Heidelberg KORD offset litho press. Its pages were folded on a Baumfolder, gathered by hand, bound on a Sulby Auto-Minabinda and trimmed on a Polar single-knife cutter.”

Also, a concert I attended recently by the young Frankfurt-based Eliot Quartett chamber group, in which they performed Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet, with guest clarinetist Laura Ruiz Ferreres. It was a small performance hall, and I was in the front row, trying to square what I was seeing with what I was hearing. Such physical exertions resulting in such sonorous beauty–it felt miraculous.

What is a book that changed or greatly influenced your life?

Mark Strand’s Dark Harbor, which came out in 1993. It was the fall of my first year in college and I was deeply homesick. I don’t know what led me to the book, only that it felt like a letter addressed to me. It gave my loneliness a different cast, like a lamp turned on inside. It was a great realization, that art could create warmth, an inner-lit life.

What is your first memory of poetry?

Being put to bed by my mother or grandmother singing “Nani Ani,” an Armenian lullaby, to me. Nani is also what my family calls me.

How have the last years changed you, and what is something that you will take with you into a post-pandemic world?

I think the past two years reminded me of what history and my family history had taught me already: the expendability of lives in the consolidation and maintenance of power. Which only deepens one’s resolve to act on behalf of the inestimable worth of people.

Who or what is your greatest creative influence?

What Dylan Thomas describes as “the force that through the green fuse drives the flowers,” a life-giving energy or feeling of benevolence.

If you were to choose one poem or text to inscribe in a public place right now, what would that be? And where would you place it?

I’d prefer not to add another sign to the public space, which is so cluttered with text and image already. People need space and silence to rest their eyes and ears, to receive what speaks to them mutely.

What do you see as the role of art in public life at this moment in time?

To be a stone in the river. To make people stop and think. To foster a sense of obstinacy and individuality of thought.

What do you want people to take away from your work?

A sense of possibility, of their own inner-lit life.

Are you working on anything right now that you can tell us about?

A new book of poems about the relation between personhood and language. They respond to what the feminist critic Jacqueline Rose has recognized as a moment in which "the knives are out," in which what it means to me to be who I am is shifting radically. The poems are correspondingly various and hybrid, incorporating other languages, translation, dialogue, and quotation.

What are you hopeful for?

I’m hopeful for wisdom in all its expressions and for the survival of its forms, such as species, languages, art, and sacred texts.