The Poet’s Nightstand

The Poet’s Nightstand with David Roderick

Couplets

Maggie Millner

“Polyamory is devouring Brooklyn,” quipped one self-appointed (Goodreads) critic, in a takedown of Millner’s Couplets. This passes for criticism now, really? All my generation had—in terms of a cultural touchstone that reflected 20-something attitudes regarding work, relationships, and sex—was Friends, an anodyne best washed down with white zinfandel every Thursday night at 8. This reader (middle-aged, suburban, Anglo, cisgendered, male) found Couplets

far more arresting and funny than Friends and any book-length sequence of poems I’ve read in years. Millner’s love story, composed in rhyming couplets (with a sprinkling of prose poems that always end in a couplet) documents the thrilling, experimental period of a young adulthood when every relationship decision feels like it carries perilous sliding-door consequences. In the preface poem, “Proem,” the book’s speaker announces that her “eye loved / everything it fell upon.” This single phrase points toward the book’s animating gestalt—its metaphor of falling especially, as we watch her stumble out of love with her boyfriend/fiancé and into an obsessive relationship with a woman. Regardless of the demographic boxes you tick, reader, Couplets will tempt you toward your original contradictory orientations. Plus, is there any better way to prep yourself for sleep than cascading rhymes? Millner’s are pliable and various, spanning the spectrum of possibilities. Many are half- or quarter-rhymes (aspects/Catholic, green/peeing), others visually or conceptually playful (could/cloud, husband/Causabon), and some buzz with humor and surprise (Givenchy/raunchy, Liz Phair/Montclair). Don’t scroll through Goodreads at bedtime. Read Couplets instead, by a poet who seems to squeeze pleasure out of daily life.

Purchase

Silver

Rowan Ricardo Phillips

I might as well cop to it: I’m jealous of writers who can express themselves skillfully in vastly different genres. For years I’ve tracked Phillips’s poems and marveled at their clockwork precision and prowess, their epic reach. Then, last year, I picked up his nonfiction travelogue The Circuit: A Tennis Odyssey, which detailed his year covering the Men’s ATP tour, a megafan’s homage that brought a poetic sensibility to bear on a sport that is a form of poetry in and of itself. Phillips’s observations about the styles of Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal informed how I experienced the poems in Silver, especially Phillips’s agile approach of playing within the strictures of lines and received forms. I admire his unique combination of grace and power, whether he’s crafting a three-part elegy to Argentine guitarist Atahualpa Yupanqui (“Blue Papa of the cosmic canticles / That the moistened plums sing to throbbing stars, / stay awhile.”) or flexing in the blank verse playground of Milton and Stevens. Phillips is looser and more humorous in this book too, perhaps a residual effect of crafting a dramatized portrait of himself in The Circuit. The longest poem in the collection, “Child of Nature” serves up a masterful remembrance of childhood. I’ve returned to it many times, such pleasant echoes (Wordsworth, Hayden, Larkin) volleying between past and present, and ending with the lulling “Years / Passed. And now from my high window, the cliffs / And canyons of these avenues call me / Back to sing through fire for their sweet sake.”

Purchase

Glass Jaw

Raisa Tolchinsky

Tolchinsky’s debut carries me in all the ways I like to be carried as a reader—through dramatic storytelling, through heartbreak, through song. Glass Jaw is a coming-of-age boxing narrative arranged as a reverse Commedia. The book’s first section situates her speaker in a community of women boxers, where she finds wisdom and love from her sparring-partner peers. Most of the poems are titled after these characters, as if the names are marks of intimacy. After two brief “Purgatory” poems, in which the boxers “carry thorns in our pockets / from all the times we spit our mouthpieces / soaked in spit, some man yelling: / what that mouth do?,” Tolchinsky turns to Glass Jaw’s main event, thirty-nine “Canto” poems that track her speaker’s metaphorical journey from hell to the earth’s surface. This elaborate architecture, which never feels tedious, gives her the space she needs to reckon with the boxing underworld’s violence: abusive training regimens, various kinds of deprivation, self-flagellation, sexual abuse. The Lucifer reigning over these circles of hell is the women’s own boxing coach, who methodically trains and grooms his charges—“Coach kept changing shape— / devil, monster, minotaur with rotted horns / but sometimes / a weeping man, dark curls / spilling across my lap...” The brutality of the sport compromises every character’s capacity for love—especially self-love. Tolchinsky arrives at the brutal truth that “a good punch is better than the best sex I’ve ever had.” A glass jaw myself, I’m convinced by her claim, regardless of which side of the punch I’m on.

Purchase

Reader, I

Corey Van Landingham

Just when I thought that prestige television and the kangaroo antics of our Supreme Court had pushed the American prose poem to the brink of extinction, Van Landingham comes along and revitalizes it by using the form to embody the dramatic collisions of marital love. In my first draft of this review, I mistyped marital

as martial, which I may as well have kept, since Reader, I

attacks the conventions of marriage as an institution. Comedic self-ridicule is a prevailing and useful weapon for Van Landingham. In an early “Reader, I” poem (most of the prose poems appear with this title) the speaker announces, “Reader, I swore I’d be a casual bride,” until, just a few lines later, she’s obsessing over the contrast between her wedding dress and skin tone, garments that might “mellow” her thighs, and whether or not she should bleach her own asshole. To approach these unreachable places, Van Landingham often turns to literary persona, playacting as Diana, Eve, the Wife of Bath, Juliet, Jane Eyre. These guises are necessary vehicles for exploring marriage’s long history of warping its participants’ moral bearing. Many of the poems’ sets are designed as communal American spaces to demonstrate that this country—another corrupt institution—bombards us with its excesses and dishonest myths. Most poets infuse their work with social criticism these days, but I find a lot of the poems too didactic or at least too earnest. Van Landingham’s satirical performances—her self-critiques—feel nuanced in a way that invites me to read them again.

Purchase

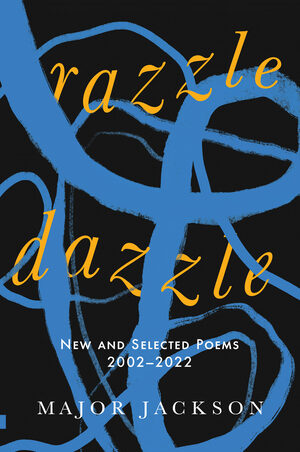

Razzle Dazzle

Major Jackson

I wish I could diagram Major Jackson’s sentences using the now-obsolete Reed-Kellogg system. If I were a better grammarian, the process might reveal designs resembling the steps of an elaborate dance—organic movements that extend, sway, pivot back. Razzle dazzle indeed. If you’re serious about your nightstand choices, this new and selected is fantastic for reading to your bedmate(s) aloud. The lulling gravity of Jackson’s lyrics might induce good loving and the pull of a very deep sleep. My advice is to read this book straight through, relishing in the 34 new poems in the opening section, then wormholing back to poems from Jackson’s 2002 debut, Leaving Saturn. In that book’s signature sequence “Urban Renewal,” a title and motif Jackson returns to in later books (Hoops,

Roll Deep, and The Absurd Man), there’s evidence of his own aesthetic already forming. After conjuring an image of a mother fussing with her child’s hair, “fingering rows / as dark as alleys,” the poem’s speaker proclaims, “I pledged / my life right then to braiding her lines to mine, / to anointing streets I love with all my mind’s wit.” This promise honors the work of Gwendolyn Brooks especially, his topmost literary touchstone. Everyone knows Jackson is a fantastic host of the popular poetry podcast, The Slowdown, because he’s big-hearted and has a knack for connecting with his audience. He’s the same man on the page, riding his own instincts and intensities. To him, poetry is sacramental, a holy vocation he’s fully committed to honoring.

Purchase