In Their Own Words

Cortney Lamar Charleston on “The Hood”

The Hood

+ + + + +

In the moonlight, a steeple of cloth crowns

the head of a good, church-going man. Pay little mind

to his serpent's tongue. His jagged teeth, deteriorated

from chewing coal. His scornful eyes as bloodshot

as the momentum of a bullet through soft tissue.

Take his word that the rope was tied of good

intentions, tied of great love for country, for family,

for manhood. In imitation of Christ, he carried

that cross here on his back. The fire set to it is not

hatred; Moses will testify it is the healthy fear of God.

Our brother in a gentler nature is only reminding us

of our proper place. And in Sunday affection, we call him

our Hood.

+ + + + +

Come dawn, all the colored kids wipe ash from eye.

Pack their schoolbags. Walk past the statuesque making

monument of the corner in front of the liquor store,

past the Pigeon Man passed out on the sidewalk. Trace

the dance of a Christian prayer across the busiest streets.

In their classrooms they read the same books that taught

their grandparents, both things kinds of expository, unhinged

at the spines from life without retirement, just like

the old janitor, sanded down to bone. His hands, callous.

If one could count the splinters that have retired in them

from pushing mops and brooms day after day, they'd have

ample to recreate the accessory of the messiah's end,

what set mold for gold chains of rapper fame.

+ + + + +

While we sleep, he knocks against the window,

shouting epithets, making threats. Fires a few gunshots

into the air for effect. We don't go outside. Don't

confront him brandishing a pistol of our own.

Don't call police, because the police are already

here keeping order. We simply wait for Law

to pass.

+ + + + +

Around here, black men disappear without notice,

never return from the liquor store a mile down the road.

The rumors will spread, say he went for cigarettes,

but in the end, became smoke drowned in wind.

Funeral held in the church a few blocks away

from Big Mama's house, its steeple a historical

allusion in the distance. Everyone passed his casket

dressed in dark, unmistakable ethnicity, even

the men crying as fluently as faucet handles turn,

the rope burns on his throat well hidden by a necktie.

+ + + + +

When night fell again, more shots. A couple

windows broken by the butts of shotguns. Fires

ignited on crosses. We slept through it all,

our bones of rock, the word in his mouth red hot,

hateful, yet warm enough to live with: the fire

a tent is pitched around in brotherhood

wherever we go that also reminds us why

our blood is easy shed.

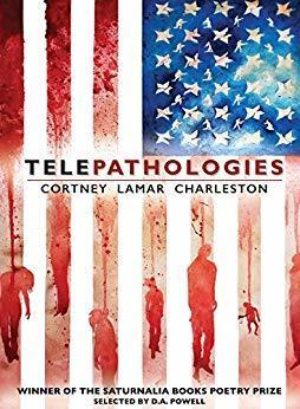

From Telepathologies (Saturnalia Books, 2017). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "The Hood"

As a quintessential 90's kid, born roughly in the middle of the first year of the decade, I spent my formative years in some of the blackest times (meaning a preeminence of Black people) America has had on record: a Black basketball player may have been the most famous man on the planet, a Black woman was redefining mass media with an unparalleled cachet across racial lines, and a countercultural Black musical genre was finding its commercial viability and spurring an influx of fresh, young Black faces into our popular-cultural consciousness―people you could hear on the radio, people you could see on television or in the movie theater, in some cases all of the above. One of the most important singular films of this time period was also one with the most profound impact on my imagination; director John Singleton's Boyz N the Hood captured critical acclaim for its depiction of a Black male's coming-of-age in South Central Los Angeles, perhaps THE shining example of what emerged as somewhat of a subgenre in Black cinema at the time: the hood flick, a Black-as-hell bildungsroman. Whether a dramatic portrayal (see Menace II Society or Juice) or a comedic portrayal (see Friday or The Wood), one could find filmmakers grappling with issues such as masculinity, sex, crime, poverty, violence and racism against the rough aesthetic backdrops of Black inner-city neighborhoods from coast to coast.

While on the one hand some could criticize the proliferation of such films as preventing the telling of the diverse range of Black narratives, I did take them as welcome productions that helped to explain some of the complexities in the world I was seeing with my own eyes roaming around Chicagoland, particularly the city-proper's South Side. The films were early teachers that, when it comes to the house Black people live in (meaning the physically and socially constructed environment we inhabit), it wasn't necessarily built by us and likewise wasn't necessarily built with our needs or best interests in mind. In my mind, over the course of my life, our vernacular insistence on shortening mention of neighborhood to "hood" has served as a linguistic nod not only to the love we have of our homes (home as place), but likewise to our homes' inability to love us back wholly, to serve as a shield from racialized violence rather than an instrument of it.

For me, as seen in the example of my poem "The Hood," this initially curious observation at some point morphed into an obsession, a way for me to creatively link larger thinking and theory around systemic racism to a more grounded, intimate and imagistic composition often expected of poetry, something I was able to do by personifying the hood as, perhaps, the hallmark symbol of racial bigotry in the American consciousness: a hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan. To me, this seemed particularly fitting for what I was trying to convey about how Black neighborhoods—due frequently to economic divestment, poor educational options, deteriorating infrastructure and social isolation—can function in service of a greater system that aims to maintain the exploitation of certain populations to the benefit of others.

With regards to Blacks and the hood, I felt a need to address this in my creative work while discussions of violence surrounding and inhabiting the Black body dominated the media and political discourse. I needed to be able to take the grandiose and political and make it, somehow, more subdued and personal; I needed to juxtapose the historical and the contemporary if only to be able to more clearly say to others look at how nothing has changed. I believe this poem was able to achieve a good number of my aims in that regard (while offering plenty of room for expansion), and certainly was a blessing to the larger collection of which it is an important part. Rather than fight too hard to depart from the "hood flick" tropes of my childhood, I trusted my instinct to write into them from a different orientation—not of discovering but of knowing expertly, and therefore what was produced was something entirely new to me, something that surprised me, scared me even, for its ability to say a whole lot of what I wanted to with a clarity and conscience only poetry seems capable of achieving.