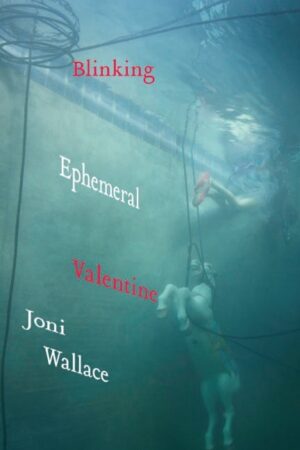

In Their Own Words

Joni Wallace's “I touch the grass I find a Hank song”

I touch the grass I find a Hank song

Tell me the dream again, its animal patches, stumplands and fields.

In the damn flyway a preacher machine. Says what makes you sleep,

says harm. And moonlight's no-word through branches. Has seen

too much coming, threadbare, sad, pine, a cowbell, goat with bowed

head.

Is it place departing, baby, that's knocksville, someone out on the lawn

long after gone. Is it a Hank song.

One and countless, a body's sorrow.

I give him dress clothes. I give him a belt, buckle, a Cadillac bench

seat, another morning for morphine's eidolic rabbit gunning. I lay it

all out, listen: chuck will's widow singsongs a nightjar. Sound enough

for an earhole called Radio Tears Reign.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "I touch the grass I find a Hank song"

As a poet I've become increasingly interested in sound: how it works on the surface of a poem to disturb the image reservoirs below it, how morphemes and phonemes carry semantics, how slight disruptions in each bend meaning, how clang association makes oneirologic. I've become more and more involved in music, blues in particular, over the past several years, so I think that informs my poetry. Lately prose poems seem best suited to these concerns because of the amphitheater-like containers they make; intentional line breaks seem to rupture.

I say this to make a template for deconstructing my process, but that said, I started writing "I touch the grass I find a Hank song" after some bird-watching escapades last summer. My kids were reading about nightjars on the Cape and discovered the Chuck Will's Widow. We loved that the bird's song is also its name; I loved how the name carries schema. That play and sound began the poem. I just let the grass vamp for a while. I didn't expect to find another song, a Hank song, there, but when I did it resonated, a childhood sound-memory passed from my grandmother to my father to me. And of course embedded in a Hank song is a man's story.

The last gesture is a poem projection, a point where it seemed an "I" should step out from behind the curtain and get into the back seat of the Cadillac. I was surprised by the impulse, but I decided to trust it. Reading it now I think I understand why. I'd been talking to a friend about the idea of "mercy" in another context, about what it means and how to define it. About a year after I wrote this poem I found my definition: being willing to enter into another's chaos. I'm sure now that the movement at the end of this poem was a reaching out toward that understanding—the poem whispering "don't sleep too soundly in the cult of suffering." So Hank gets a belt buckle and a spit shine, another day and a hit. He gets a radio show. He can transmit and receive. There's a Beckett harmonic. There's a nightjar.