Old School

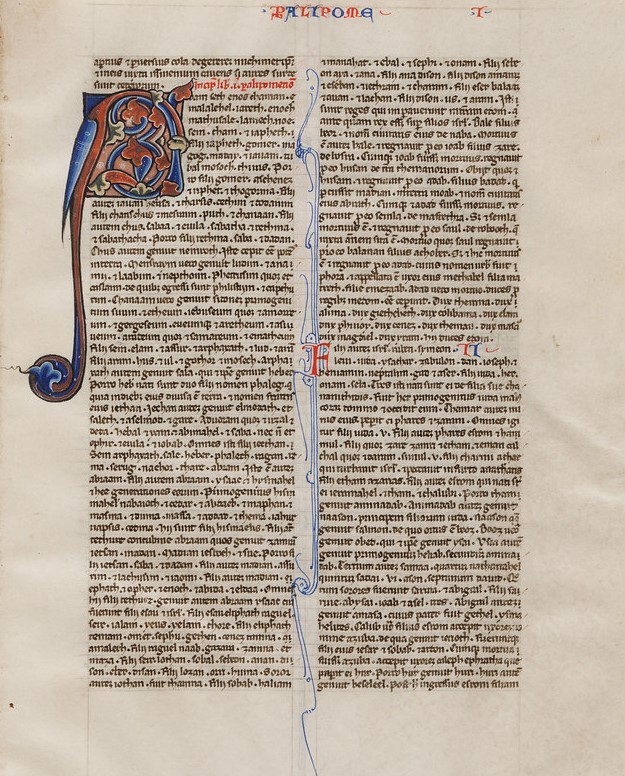

On the Vulgate Bible

I sang in Latin almost every Sunday for two years before I knew what any of the words meant.

Ecclesiastical Latin (then Classical, then Medieval) taught me compression in a way that was at first mysterious. I believe I loved the words more before I knew what they meant, when I was a chorister with vague sentiments and excellent pronunciation. Then, after Latin became my primary course of study in college, I came to love the liturgy as one comes again to love in a long marriage, after you know what all the words mean.

I'm not talking about Christian doctrine, mind you; I'm talking about the mechanics of the Latin.

In 1585 the Franco-Flemish composer Orlandus Lassus took a verse from the Vulgate Bible and set it for five voices. As in all great lyric settings, his underlay amplifies unexpected syllables.

Here is the Latin (Isaiah 35:4):

Confortamini,

et iam nolite timere:

ecce enim Deus noster retribuet iudicium:

ipse veniet,

et salvos nos faciet.

When I was in Latin A, I translated confortamini as "be (pl.) comforted." What an imperative! The rest of it is simple:

and now fear not:

Behold, our God will bring judgment:

He will come

and save us.

For the second sopranos, Lassus set the first word as if it were eleven syllables and not merely five, and until the middle of the middle line, the downbeats align with unstressed syllables. After God brings his judgment, the music and text stop arguing.

Ipse is a pronoun that adds a variable amount of additional emphasis. In this context I believe its effect is ennobling.

In case languages, as you may know, articles and particles are few, and word order, which is somewhat unfixed, becomes a crucial element of style. The indirect object in the last line is tucked lovingly within the verbal phrase.

The penultimate chord sounds dissonant to a contemporary ear; it contains both the normal and augmented seventh tones of the scale. That is, it contains two tones adjacent on a standard keyboard. Though this interval wasn't considered dissonant in the sixteenth century, by the eighteenth century it was no longer used. When it reappeared in twentieth-century music it sounded new.

None of that has anything to do with the text, but it was crucial to my coming to love the effect of this particular passage. I so loved the setting, I wanted to know everything about it. The desperate, irrational faith and the confident, efficient language stand in such gross disagreement. If you want to move your reader, write more coldly, writes Chekhov, as I tell every writing class I ever teach. The Vulgate Bible is written in ice.

Some time after learning the Lassus setting, I discovered my original translation was wrong. Confortamini means be strong.