In Their Own Words

Carrie Fountain on “The Spirit Asks”

This is the life with fried eggs.

This is the life with Pyrex dishes

of many sizes, none of which

I purchased myself. This is the life

with the boy who’d eat chicken

nuggets for every meal and the girl

who’s asked four times this week

if she can please clean the cat’s ears

again with a Q-tip. They are dirty.

No, they’re not. This is the life

with lives in it so small we have to

put up a sign on the front door

DON’T FORGET THE FISH, or

we’d forget the fish. This life:

sometimes I feel myself so deep

inside it, blessed so painfully, so

painfully blessed, pushing into it,

pushing—and yet I cannot

get through. I want too much.

I want a God who will save us all

and a God who will feel the little heat

coming off the candle I lit in the grotto.

A God in heaven, but a God here,

too, you know? I want a God like

the one I tell my children about, the one

who loves everyone. Even Trump? Well,

I guess so, yes. Even Trump. Please

give me a God that exists. That’s all

I’ll ever want. And the spirit says,

OK And I say, Really? And the spirit

says, Yeah. Probably. Yeah.

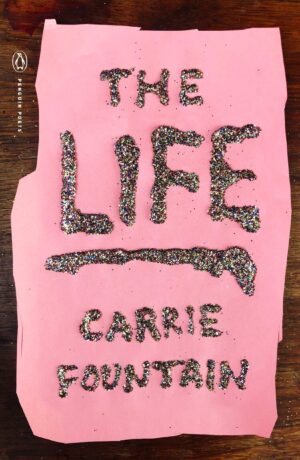

From The Life (Penguin Poet, 2021). Copyright © 2021 by Carrie Fountain. Reprinted with the permission of the author and publisher.

On "The Spirit Asks"

Now that I’ve been writing this long into my life, I’ve come to understand writing in a different way. It’s hard to articulate, and it feels vulnerable because part of me still finds it ridiculous, but for me, the discipline that returns with my writing practice is a spiritual discipline. When I’m awaiting it, I’m awaiting the spirit. When it’s here, I’m attending to the gifts of the spirit. It’s not really about making books, though of course it is. But, more essentially, it’s about returning to the attentiveness of that discipline. Which is merely taking a breath and feeling it. Looking around and seeing. It’s the easiest and the hardest thing to do.

What is holy is all around. Isn’t that the most difficult thing to come to terms with?

It’s all around and all the time.

This poem is an imagined conversation with that spirit and addresses the essential question troubling the last many years of American life for me: how can we understand a god of love if we don’t ask how that god feels about those who are despicable in word as well as in action?

It was hard to even use the name of the former president in this poem. It does feel like a curse. And I avoid it throughout the rest of the book, though he haunts many of these poems. But it felt necessary to name him here.

I am still engaging with this question from my children about who exactly deserves god’s love. Kids want exacting answers. They want yeses and nos. “Even Trump?” is a question I will never be able to answer. In many ways, it is a question more difficult even than “Does god exist?”

In this poem, I imagine a spirit who understands much more than me. But not even this imagined spirit can answer definitively.