In Their Own Words

Lauren K. Watel on “The Island”

The Island

I swam without ceasing around the rocks guarding the island, the looming black rocks slick with surf. In sunlight they shone like onyx, as if polished. In a storm they were flat and dull as slate. I used to search for an opening in the rocks, some small gap through which to slip my body, in the hopes of finding calmer waters, because the seas were so choppy then, the waves churning as if in anger, the foam roiling up to the rock tips, but the rocks made a wall around the island, a wall that seemed impenetrable. I swam around the rocks with my thrashing crawl—I was never a good swimmer—always wondering where my strokes would take me, the sun overhead like a deity watching my slow progress, scratching its head and muttering, Why her, why here, swimming in circles? I could never find a space in the rocks through which the island was visible. I could only imagine a place, wild with raw beauty, running with springs and vines, where the flowers grew as high as trees, the trees high as skyscrapers, where horses galloped on the sand, horses majestic as clouds, leaving sand upturned behind them like trails of sugar, which the waves would wash over, wash away, where blue butterflies and tropical birds dotted the flowers and trees like confetti, and all the fruit I could bear to eat. What a vision, this island. I swam around it for years. If only I’d thought to swim away.

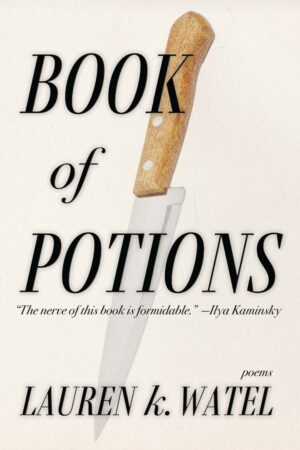

Reprinted from Book of Potions (Sarabande, 2025) with the permission of the poet.

On "The Island"

Like all the pieces in my debut collection BOOK of POTIONS (potion = poem + fiction), I wrote “The Island” in a state of intense agony and anxiety. I wrote as quickly as possible, in a fever, without stopping or thinking, the way you might howl aloud, alone in your house, overwhelmed by feelings. I wrote without any ambition, simply to make my hand pick up the pen and move it down the page. I wrote out of personal necessity, desperation even, to get things off my chest, as they say. Because the things on my chest, those weights all of us carry, they were crushing me, and I was finding it hard to breathe.

For a long time I didn’t understand “The Island.” I knew it was telling me something about myself, something that deeply unsettled me, but I wasn’t sure what that might be. Most of the potions left me shrugging this way; with some I’m still shrugging, even now. One thing I did know: Every piece was somehow trying to express a complex of feelings, a complicated state of mind. Not by describing the feeling itself—by saying, for instance, “Oh, I’m so devastated and enraged”—but by transmuting the feeling into a vivid, concrete scene, sometimes like a fable, sometimes a dream, other times a dialogue.

I doubt I would’ve bothered to delve into “The Island,” but an extremely intelligent editor asked me to rewrite the ending, prior to publication. An excellent suggestion, because the original ending simply rephrased what I’d already said. However, in order to create a better ending that fit the logic of the piece, I had to make sense of that logic, to figure out the literary strategies “The Island” was using, what it might be revealing about my inner life. To that end, I approached my own work the same way I would approach the work of a writer I didn’t know, rereading the piece again and again. An appropriate process, as it turned out, because how well did I know myself?

Since the potion begins, “I swam without ceasing,” I started thinking about swimming and its role in my life. As I say in the piece, “I was never a good swimmer.” Just before the pandemic hit, I’d decided to relearn the freestyle. I became obsessed with the Japanese swimmer in the YouTube video “The Most Graceful Freestyle Swimming,” a marvel of effortless elegance in the water, ten million views and counting. I swam back and forth, back and forth, but I couldn’t even make it an entire lap without stopping, because I was holding my breath, trying to perfect my form. After years with no progress, I had to take a break. The potion made me realize that swimming epitomized my tendency to get stuck trying to do an activity flawlessly, at the expense of doing, and enjoying, the activity for the pure joy of it.

Why was the speaker swimming ceaselessly around an island? Eventually the structure of the piece, composed of two different visual descriptions, gave me a clue. The first depicts not the island but “the rocks guarding the island,” how they look in different weathers, as well as the water, roiling and churning, and the sun, mystified by the swimmer. Just over halfway in, the piece turns to another description. However, because the rocks make “a wall around the island,” the speaker can “never find a space in the rocks through which the island was visible.” Therefore, the second description, of the island itself, is an imagined description, of a fantastical place nonetheless depicted in vivid detail, an Eden-like daydream of tropical beauty and majesty.

The piece ends with three short sentences: “What a vision, this island. I swam around it for years. If only I’d thought to swim away.” The swimmer is trapped in a never-ending cycle, circling a solid wall of rocks, in choppy waters, under an uncomprehending sun, hoping to catch a glimpse of the wonderland she imagines beyond those rocks. A foolish endeavor, to swim around a vision for years, but I recognized myself. My stubborn attachment to fantasies about perfection, to lofty and unrealistic youthful ideals. Also, my constant disillusionment over people’s flaws, my own especially. I had a hard time accepting what the world was really like, what people were really like, and I longed for a place I could never find, because it didn’t exist.

Just as I came to a certain understanding of “The Island,” I came to understand myself a bit better. I believe, though, that my interpretation is one of many possible interpretations, that the island, the rocks, the swimmer, could signify so many heartaches. Every reader has longed for a glorious imagined place, true to their own interior, that hides behind that impenetrable rock wall. Occasionally I still catch myself thrashing around the island, hoping to find a space in the rock, to reach calmer waters and stagger onto the shore. Mostly, though, I’ve swum away. Though the island is still there, on the page, in my book, along with the person who wrote it, the version of myself who couldn’t stop swimming in circles.