In Their Own Words

Lena Moses-Schmitt on “The Train”

The Train

You know the hard days are coming.

But in the future, say, two weeks off.

You see it over the horizon,

stitching quietly toward you.

It wails. But you’re not riding it yet.

For now you’re safe.

The snow is bright, and blinding.

Your heart leaps at it, an ember

that hisses as it hits the blankness.

Leaps at snow or leaps, through time, at that future blankness?

All this cold is dazzling.

So dazzling you forget to console yourself

in the second person.

The professor in my head says, don’t use so many adjectives.

Marie Howe suggests trying to resist metaphor

in order to endure the thing itself.

Okay. So what words are left? What joy?

All the geniuses love verbs: words like waits

or leaps or runs.

I like nouns too. Snow. Ember. Train.

Taking this inventory, I feel like a giant human

playing with thumb-sized furniture,

sliding concepts into their wooden rooms.

I put my eye into the window.

But it makes the room run dark.

It’s me—me who is descending.

Also me who runs.

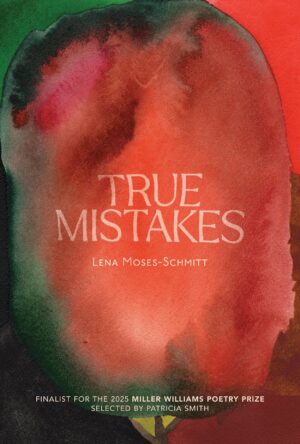

From True Mistakes (University of Arkansas Press, 2025). Reprinted with the permission of the poet.

On "The Train"

I wrote this poem when I was in Vermont for three weeks, in February. By virtue of being in a new place, I was enjoying myself, but I was keenly aware I was not living “real life” with all its attendant problems, pressures, and obstacles. I was, predictably, at a writing residency, and it was winter, a season I hadn’t truly encountered in eight years—in three weeks I’d return to my apartment in California, where it would be 65 degrees every day. The novelty of seeing snow for the first time in years refreshed my sense of possibility, while the idea I’d soon return to my real life, to real feelings and problems, my real job, my beautiful yet lonely neighborhood where for the past three years I’d undergone waves of depression, bore down on me. I knew I was on a temporary vacation from reality.

The start of this poem came while I was walking through the snow up a hill and then turned to look out over the gray and white Vermont landscape. I actually cannot remember if I saw a train in the distance—I don’t think I did, I think I just had the sensation of seeing a train in the distance, the train being my life, a mood or episode I could never escape, following me. It was a quiet and weirdly calm feeling, one I tried to convey by the brief, end-stopped lines. Because I was ostensibly in Vermont to work on my first book of poems True Mistakes (where this poem appears), I had all these different voices in my head about how to write and by extension, how to think, how to absorb experience. What does it mean to think to myself in first person versus second person? (In the first draft of the poem, I intuitively pivoted from second person to first person without realizing, so I added the line “So dazzling you forget to console yourself / in the second person” as a way to explain to myself—and perhaps to the nit-picking workshopping voices in my head—why that switch happened.) What does it mean that I love metaphor—did it mean I was not really looking at my life, that I was constantly, instead, turning from it? (The brilliant Marie Howe quote is from a 2017 interview she did with the radio program “On Being,” a conversation I think of often, and which helped me think through my own ideas of metaphor.) Am I me when I am thinking or am I all the writers I love and all the professors who taught me? Which is the part of me that is looking and which is the part of me that is being looked at (and judged)? Where am I, actually?

Also: what does it mean when the words or framing devices we automatically reach for to process our own experiences are called into question? When we cannot trust our own intuition, what can we trust? The end of the poem attempts to capture the claustrophobia of those questions, and the ensuing panic over the futility of being yourself. The image of sliding words around like dollhouse furniture is funny to me, and also, perhaps, aspirational—to think I could have that much control! I had wanted to escape not only my life but myself; to be blank and new as snow, full of potential, not yet stomped on by my own thoughts. Yet in trying to escape I was making myself into my own worst judge. I was trying, in this poem, to make myself okay with being myself, to understand that I have more control than I think, simply by leaning into my own predilections instead of running away from them—I don’t necessarily need to fear the train.