In Their Own Words

Destiny O. Birdsong on “Pickle Goddess”

Pickle Goddess

after ASMRTheChew

I’ll eat my supplicants, wearing my carpet green

suit and red lipstick the mothers warned me about.

I do it for the sting of vinegar beneath

my loose crown, for the way it changes

the shape of my mouth. I could be silently

singing hosannas or having orgasms, followed

by the sound of taut skin breaking between

teeth. On the days my joints don’t ache, I lift

the gallon from the bottom of the fridge.

The candy lady is dead, so I do the honors:

fish for the big one, fingers puckering

in the chilled brine, the small cut

on my knuckle rinsed alive again with want.

I choose one with the deep color

on one side, lighter everywhere else. Carve a cross

in the pale butt, stick a Jolly Rancher inside.

I still know how to eat around it, pushing

its winnowing jewel deeper with my tongue.

Back in the day, I’d rub two quarters in my pocket

and sidle down the block, palate already

itching for that first note of garlic

like a money shot. I’m so glad my mama

don’t pay for nothing these days, and nobody

is around to tell me I’m smacking too loud.

That no one can see the small gap between

my incisor and canine, where the best

morsels get stuck, and I have to suck them free.

The women in my family raise a hand

to cover that space when they laugh, but I live

for what stings without bitterness, for what

is still edible after months and months

discounted on a shelf. For what salt

serves as sacrament. For false fruit.

For whatever sates me into a raw-mouthed

sleep. For whatever in you is ready to relish

what’s left in me—unjarred, unlicked. Still sweet.

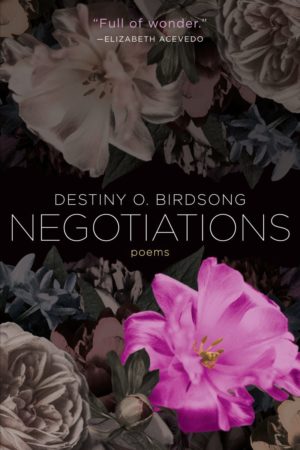

From Negotiations (Tin House, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On “Pickle Goddess”

I love watching black women on camera because I am a black woman who likes to see herself. While watching, I’m distracted from popular culture’s blaring reminder that my thighs are too fat, my nose too large, and that the blackness of my body looks much better on bodies that are, in fact, not black. One evening in late 2017, when I was supposed to be working, but was instead messaging a friend while tricking off on Facebook, I came across Spirit Payton, creator of ASMRTheChew. As I scrolled, a still frame of her biting into a pickle stopped me in my tracks. I pulled up the video. I pressed play.

There was so much to love about what I saw, but let me begin with the pickle itself. I grew up in small-city Louisiana, in a neighborhood with a Candy Lady, who sold freeze cups, cookies, grab-bags of potato chips, candy, and pickles. All summer long, the neighborhood kids scraped together quarters or sweaty dollar bills we’d begged from our aunts or godparents, and headed her way. Eating candy-spiked pickles in front of our floor model television while watching videos on The Box, ribbing my sister and play cousins about who was eating them the most lewdly, and trying not to spill pickle juice on the floor my mother had probably just mopped was my first crash course in the literal and metaphorical truth that some things taste sweetest when submerged in salt.

I could love the video for that alone, but there’s also Spirit, doing all the things my mother might have swatted me for in those bygone days: smacking, chomping, enjoying the ritual of consumption. So much of my childhood was studded with directives designed to make me a palatable black woman in a world eager to spit me out: don’t sit with your legs gapped open; keep your mouth closed when you eat your food; don’t wear that color lipstick. Red was for unsaved women. Showing anyone the inside of your mouth was an invitation for the kind of attention you weren’t supposed to want. Even when my mother laughed, she instinctively covered her mouth. Joy had its restrictions.

But Spirit isn’t adhering to any of this. Her crunches are wet and loud, her lips a fiery vermillion. Before sliding out a carbuncular kosher dill and tapping it ceremoniously against the jar, she takes a loud slurp of pickle juice. My mother would have been mortified. I loved it.

And I love the imperfections of the video, which, for me, aren’t imperfections so much as they are resistances to the cult of perfection that most of us buy into when we post things online, doing dozens of takes and testing out filters, hoping to achieve a kind of flawlessness that—at least for bodies like mine—is impossible. In Spirit’s case, the fingernail on her left index finger is broken, and when she holds up a pickle for the viewer to bite, then pulls it back, the pickle is visibly intact, unbitten. There is a gap between her two front teeth, through which you can see her tongue as she eats and talks. I have gaps too, between my incisors and canines. Watching her consume, share, smack, and sprinkle pickle juice around the altar of the table like a blessing brings me joy steeped in the majesty of both my body’s beauty and hers.

After watching it a few times, I sent the video to my friend. Why is she wearing a pickle suit and dancing? he asks. Idk but that’s the best part, I reply, she’s a cannibal. He laughs, Or she’s their god. And a light bulb comes on. Black woman as pickle god, I tell him. That is a poem.

“Pickle Goddess” comes near the end of my debut poetry collection, Negotiations, because it is a difficult book that I wanted to end in joy. In the poem, I tried to nod to all the things I mentioned above: the simple pleasures of my childhood, growing out of the policed nature of girl-rearing, and the ritual of eating familiar foods my body can still tolerate. I also wanted to point to new post-traumatic joys, like relishing the erotica of my every movement in the absence of lovers—though that door is always open, as the final lines suggest. When I wrote “Pickle Goddess,” I had no idea Spirit and I had so much in common: chronic illness, an affinity for alternative medicine, and food consumption as healing practice. Such is part of the serendipity of writing, and a testament to the miracle of its power: when a poem connects the lived experiences of its speaker, subject, and/or reader in ways the writer herself couldn’t have anticipated. It’s the most radical of empathies—and the most effortless—when I am stunned by an unusual kind of beauty, and, upon closer inspection, find a sliver of myself tucked deep in its tart flesh.