In Their Own Words

Keetje Kuipers on “The Magician at the Woodpile”

The Magician at the Woodpile

The blue tarp is covered in little pools

of water that shimmer like sequins

everywhere a wrinkle has gathered. I pull

it off with a flourish and start digging through

the kindling and logs until I find the dicks,

all of them, hidden in the back of the pile.

The dicks I took in my mouth. The dicks

that didn’t ask permission. The dicks I loved

and the dicks I never really knew. I remember

holding them in my hands—how soft the skin,

how various the shapes—and cooing to each one,

You’re the most beautiful dick I’ve ever seen,

as if wonder were the only register my voice

could work in. Now I stack the wood the way

the dicks must have learned at camp,

with the kindling at the bottom and the big

logs on top. I add the dicks last, like a little pink

crown of thorns. Then I light the whole thing on fire.

I expect to see spiders come running out, rats

even. I expect to hear screams. But there’s nothing.

Just a fire making me warm, even as the sun

goes down at my back, everything but my face

suddenly in darkness, like I’m performing

a magic trick, like the magic trick is me.

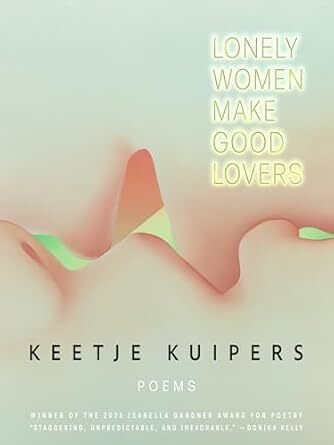

Reprinted from Lonely Women Make Good Lovers (BOA Editions, 2025) with the permission of the poet.

On “The Magician at the Woodpile”

I’ve always felt fairly illegible. Indecipherable to the gaze of most. This isn’t an uncommon feeling as a human, I know. We’re all ultimately unknowable, and what a passing stranger—or even a co-worker, neighbor, or casual acquaintance—can grasp from the clues of our outward appearance and manner offers only a paucity of information about our true selves. And yet it’s frustrating—wounding, even—to feel unreadable. Maybe this is why our current culture so loves a label, a name we can choose for ourselves. The problem, of course, being that in order for that label to function as a way of signaling and symbolizing our identity, we’re forced to shout it until the world decides to listen. For some, it’s an issue of class; for others, it's race. Then there’s gender, sexuality, religion, national origin, immigration status, even the question of country mouse versus city mouse. Identity—the way we see ourselves in the landscape of the world—is an integral human quality and need. So it makes sense that we want so desperately to be seen as ourselves. But how to show anyone?

My work is autobiographical and, therefore, yoked to questions of authenticity, so this conundrum of legibility is one I’ve repeatedly found myself rubbing up against in my poetry. While it’s important to me personally to be seen by others as I see myself, I’ve also always wanted my work to make a kind of easy sense for the reader: each line within the context of the poem, each poem within the context of the book, and each book within the context of my larger catalog. The result was that for years, I’d been writing poems that worked too hard to be carefully calibrated in a way that might actually elide the complications of who I am, smoothing over the gaps and buffing down the spots that I felt stuck out too much. But when I started writing the poems for my fourth collection, Lonely Women Make Good Lovers,

the fallacy of this exercise finally—and very belatedly—started to become clear to me. I am not one single thing, so why would I try to write myself as if I was? That’s when I began writing away from “easy sense” into the unexplained contradictions at the heart of how I see myself as an individual and as a citizen of this world.

What I discovered pretty quickly was that the only way I could do this was by using magic. Magical realism has a long and glorious tradition in fiction, but, aside from some key figures like Alberto Ríos, has perhaps played a less essential role in poetry, even outside the U.S. Scholar Luis Leal has said, “In magical realism the writer confronts reality and tries to untangle it, to discover what is mysterious in things, in life, in human acts. The principal thing is not the creation of imaginary beings or worlds but the discovery of the mysterious relationship between man and his circumstances…. The magical realist does not try to copy the surrounding reality or to wound it but to seize the mystery that breathes behind things.” My poem “The Magician at the Woodpile” was my earliest attempt to claim and, ultimately, make use of a little bit of that “mystery that breathes behind” my very self.

As I say in a different poem in the book, “I am complex / as any being.” For me, much of that complexity dwells in my sexuality, which can’t be easily fit into a box with a neat label. And anyway, why would I want it to?