In Their Own Words

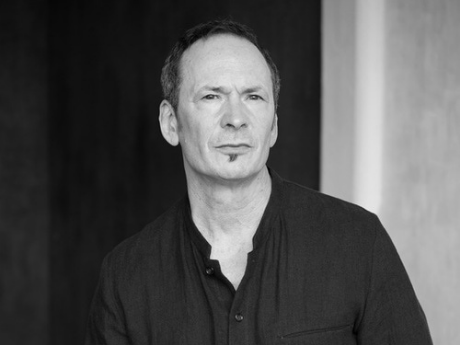

Forrest Gander on “Aubade”

Aubade

For Ötzi

Pulling the arrow’s shaft from his own shoulder

on the east ridge with and an axe of solid copper and

ibex meat undigested conifer pollen, so late spring

bearskin snowshoes a pouch with his firelighting kit

flint flakes and a tinder conk the mushroom kindling an ember for hours

after he turned onto his stomach froze & thawed & froze again

for 5,000 years what beyond pain

did he hear as the light flickered flickered on the mountain’s face

what entered his body through the ears

through the desolate desolated desolation of his eyes

what did he take for which he had no name

From Twice Alive (New Directions, 2021). Reprinted with the permission of the author and publisher.

On “Aubade”

Ötzi is the colloquial name given the “the Iceman” who was found in the Ötztal Alps in Italy in 1991. Over 5,000 years old, Ötzi was evidently murdered, shot with an arrow while he camped on the side of the mountain. Because his tattooed body froze and was preserved soon after death, Ötzi is the oldest natural human mummy from Europe, and a great deal has been learned from studying him. We know, for instance, about his his diet, his clothes, his illnesses, where he lived, and how and with what tools and weapons he hunted. As it turns out, he was very savvy about mushrooms. He carried two species of polypore mushrooms, one of which is used as a treatment for intestinal parasites (which he had). He also carried a fire-lighting kit and a tinder conk, a mushroom that retains heat and could keep a coal hot for many hours. Since my newest book, Twice Alive, is concerned with mushrooms and lichen (as well as with human intimacy), the mushroom connection was of particular interest to me. In writing the poem, I broke the syntax into pieces separated by a gap so that the rhythm was halting, staggered, as Ötzi’s own movements, breath, and consciousness might have been as he lay dying. His killers must have been nearby, and I thought about him listening for them, lying face down in the snow, aware of the last sounds around him. He would have had a language, of course, and I wondered what words, in his pain, in the swirl of his mind, might be there at the tip of his tongue at the end of his world.