In Their Own Words

Hannah Brooks-Motl on “Idyll”

Idyll

A feather in a wire apparatus plus electronic exhaust

The rat and I in mutual cold

In which the sky proposes wisps of sky information

An old paralysis, you feel that?

These vast affairs with serious night

The old phases of love, someone sang of that

This casual involvement with the skin of profit

In a movement beyond art, come tell me that—

Of a lion’s head and the beloved claw

Creation gathers my filth & your filth: we nod off in that corner

Down the hillside forms tumble

One passenger’s common mistake, it was a curse

Out of the trash of the human poem

To think like that and with little acclaim

Into the gentle bobbing of thistle and candy

This could be a long tradition

Pleasurable scales of wheat lands & corn lands & edge

These former companions through the spider’s web—

Lovely apple, cleo, phil

An intermittent childhood cannot tell us about clouds

Lovely apple, cleo, peach

And various tenting beauties of flowers

It was clearer how to mean to be alone

As convention inserts the presence of today

A few words, throw those down

In lush afternoon vocabulary, dreamy tender cover

They hunt us through the bitching forest

Today is nothing in the work of art

On “Idyll”

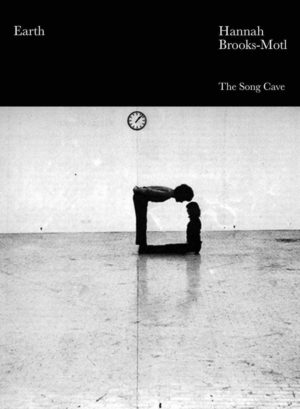

I saw an actual feather in a wire apparatus once. I was staying with friends who were renovating their house. There was the stuff of house renovation all around. In one corner: this. I don’t know what kind of feather. I don’t know what the wire thingy around it was for. The fact of these objects, the mystery of their arrival or intended use, are not analogues or allegories or metaphors for poetry. They were just arrangements, a happenstance I managed to catch once. “Idyll” organizes such dispositions, through diction. Poems are their words in a particular way. I try not to sentimentalize this. To be—to use—a word is hazardous, historical. Poems, this poem, also contain flashes of what John Dewey once warily called “past enjoyments.” Those poetic tropes and contents empty finally now and forever. Childhood, clouds. I share Dewey’s fascination at what used to be pleasing, also his concern that old pleasures might unthinkingly appear or be reproduced within an utterly changed present (“they hunt us…”).

An idyll is a short descriptive poem. Idylls demonstrate rustic life, paint picturesque scenes and incidents. A hillside, a forest, a peach. In this poem genre seemed a kind of knowledge, though I don’t recall that I started there. At the time of my visit, the years around it, I was preoccupied with the long pastorals of eighteenth-century English poetry—men were rusticating, cucumbers were growing, I was often drowsy. Idyll’s homonym (in US pronunciation anyway) is idle, and to be idle is philosophically and politically suspect. Idleness demurs from assumptions that human value and worth relate to toil, to measurable outputs, to communities of mutual recognition. Negative politics, anti-politics, also haunt pastoral, one of poetry’s oldest genres and thus forefront of its obsolescence. The word idle too once carried some sense of “empty” “vacant” or “void.” Poets inhabit peculiar forms of idleness, as bodies engaged in unrenumerative practices such as the making of poems, as supplicants to empty contents and unfashionable modes, describers of obsolete voids and use-questionable structures. They honor nothing.