In Their Own Words

Jake Skeets on “The Body a Bottle”

The Body a Bottle

cracked hawkweed sacrum

nectar bitter from the flower

its pelvis dyed matter dark

petal to sepal frazzled

limp like a lazy eye

weed bud calcified

on a bottle of muddy gin

water swollen in the body

yellow madder crushed into sand

fresh blood oozes at the lips

the hair matted root

inlet of a river done in

On "The Body a Bottle"

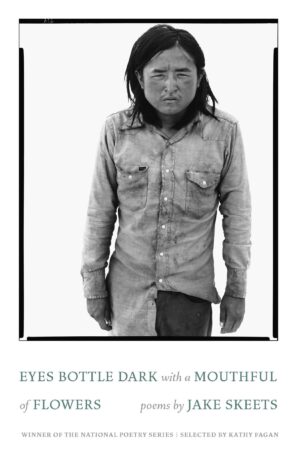

The poem began with a body and a bottle. It was late afternoon and I was driving back home from my summer residency at the Institute of American Indian Arts. The drive was several hours through high and valley desert, country road and freeway. During these long drives, I often find myself capturing certain images; quick flashes of scene on the side of the road. My partner does most of the driving so I simply look out the window. I remember this particular drive home because we drove straight through Gallup, New Mexico instead of stopping like we normally do. I consider Gallup a hometown because I attended the middle, junior, and high school. However, I lived a few miles south of Gallup. A simple Google search will narrate the history of Gallup as a railroad town named after its paymaster. With the boom of Route 66 came the boom of Gallup and because the town neighbors several Native Nations it became known as "The Indian Capital of the World." Today, the nostalgic banners and signs of Indian Jewelry and Route 66 are still on display. I have seen these signs so often that I do not even register them anymore. They become backdrop to another story. Gallup's other nickname is "Drunktown."

We drove west on the interstate toward Flagstaff to make our way back to Phoenix. I was looking out over the dissolving city, into the fields of sage, rabbit brush, and tumbleweed. On a frontage road next to the freeway, I saw a single police car, no lights, and a policeman standing over a body. I quickly looked away as it is not good to stare at a dead body. Of course, I assumed the body was without life, except for the life surrounding the body. I comforted myself with the idea that perhaps the body was simply asleep on the warm sand. If the body was dead, there would have been an ambulance and more police cars. Though the body was just seen in-passing, a quick image off the main highway, it was etched into my memory. I pondered the body, noticed its details, and began to shape the image that would inform the poem.

I began to work on the poem once I got home. I usually use a variety of methods to write a poem. I am not one for ritual when it comes to text and the page. Instead, I try everything. I have faith that the trigger of a poem, if realized enough in the mind and if its ready to be shared, will find its way into the poem on its own, organically. The energy of the thing will find itself represented on the page. The best way to honor and hone energy is with language and the best way to honor and hone language is with craft. For me, craft means attention to sound, the field of the page, text, image, and play. I had the image in mind: a body on the side of the road. I was drinking an IPA local to Phoenix as I attempted to write this poem and I was fixated on the darkness of the bottle. (This fixation would ultimately reshape my entire manuscript.) It is a color I tend to always see and one I tend to smell. Generally, when a body is found in the fields of Gallup, alcohol is considered the culprit, the trigger, the smoking gun. I imagined the many bottles I see on the side of the road and the title came first: the body and a bottle. I set out to write a poem that compared a body to a bottle on the side of the road.

I am obsessed with the line; how the line moves text and sound on the page, how it choreographs the objects of the poem, how it dances the body across the field of the page. This poem went through several versions of itself but never quite found a deep structure. I like to chisel my poems into place on the page and then let the line free them up to dance for the reader. I scrapped the entire thing and opened a new Word document to start again. This time, I began to rewrite all the lines I had written into the couplet. Joan Kane taught me that the couplet should speak toward the parallel of the lines; how does one create rhyme and stop between the text and images and what are the purposes. Santee Frazier would always ask where does the poem begin, where does the poem leap from the page. Sherwin Bitsui taught me about expanding and deepening image to its farthest limits. So I first began with image. I thought about a scalp underneath dark hair; if one were to spread the hair to expose the scalp what would one see. I answered maybe they would see a river bed, a dried river bed running down a map. I thought about the wild flowers that grow around the found bodies and thought about their bodies; the sacrum of a flower, its pelvis. The flower is no longer just a flower, it is composed of nectar, petals, a sepal, an ovary, and life that pumps through it all. These contradicting images then pushed me away from the poem into its structure. The chiastic structure fell into place and that is where the poem would leap off the page back into itself. So the words then fell into the skeleton, into the beginnings and ends of the lines: cracked flower, sacrum nectar, frazzled pelvis, dark petals, limp calcium, weeds shaped into an eye, a body and a bottle, gin and water, madder on the lips, blood on the sand, an inlet and a root, hair leaked over a dried river bed. The couplets then fell into place and purpose.

Chiastic structure is one I parse through often when I think about poetry and poetics. It is generally associated with the Bible. I find it useful and impactful in my poetry because it is a structure of intimacy. It is an intimacy between concept and text, image and line, an intimacy of push and pull. Chiastic structure finds some similarities to Diné thought and lifeway because it creates circular motions within a poem. There is no real beginning or ending of a line. Instead, the line begins somewhere in the middle of things just as we start a dream in the scheme of things, just like the beginning of the universe when light suddenly sparked in a black world. Time is never linear in poetry just as time is never linear within Diné prayer and song. Driving through Dinétah, you see time in the cliffs. Each layer of sediment, each protruding boulder, each field of dead and living bushes is composed with time and represents deep time. We drive through time, with time, ahead of time, on time, behind time, and of time every day. Somewhere in the middle of all this, a poem exists. I hope to spark as many as possible.