In Their Own Words

Jameson Fitzpatrick on “How to Feel Good”

How to Feel Good

There was the idea of love and then what.

Man Discovers Fire, Burns Self.

Practices losing weekends, months,

a season even, never enough not to be too much.

Like always wanting more cocaine

until the moment he wishes he’d done less,

the middle of the night is so short

and morning so long

when slept through. That’s one solution.

Sex works best, probably,

but an excess of feeling can be exhausted.

I mean exhausting. I tried exercising

but I liked not exercising too much.

Poetry if you’re hopeless,

novels if you like to feel smart,

though feeling smart only feels good

if you’re not. Better not feel

too much or too little of anything

to feel good. Balance is recommended

unless you hate balance because, like me,

you have a personality disorder.

You might try TV.

Maybe don’t have a personality disorder.

Self-care is hard but there’s no comedown.

Walking helps, whatever else

they tell you in therapy.

No feeling is final, Rilke writes

in a poem about god I pretend isn’t.

But you learned that already

on your way back up from the mirror,

from the burning, the whipping your head skyward,

the oh-god-why-can’t-it-always-be-like-this.

There is no god, there is no reason.

Everything is as it should be,

which doesn’t square politically but that’s DBT.

You have to choose what to feel bad about.

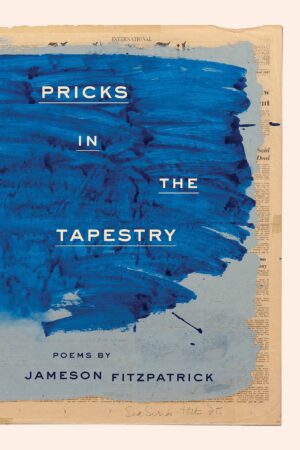

From Pricks in the Tapestry (Birds LLC, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author and publisher.

On "How to Feel Good"

I remember little about this poem’s composition, which is unusual for me. I was probably depressed when I wrote it, hence my preoccupation with its titular project. An email search turns up a draft I sent to my friend Diana (Hamilton, brilliant poet) on May 31, 2016. Her belief in the poem facilitated my own, as did her astute feedback (it was Diana who suggested that poetry was for the “hopeless.”)

The oldest line within—the characterization of a certain chemically-induced euphoria as “the oh-god-why-can’t-it-always-be-like-this”—actually kicked around my brain for at least half a decade before I put it down here. I suspect the invented, run-on compound word is a move I cribbed from Marie Howe, one of my greatest teachers, although this poem otherwise bears little resemblance to hers.

It’s a rather restless single stanza, shifting POV and cycling through a variety of imperfect tactics, ranging from the admittedly ill-advised (“the oh-god-why-can’t-it-always-be-like-this”) to the more tried-and-true skills (“Walking helps”) that I acquired while undergoing a two-year course of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy after a brief psychiatric hospitalization in 2012.

One of the homework assignments for my DBT group that I struggled with most was when we were tasked to come up with “cheerleading statements” for ourselves. Though I was—and am—a DBT believer, the practice hewed a bit too close to the affirmations of New Age self-help for my comfort. After I relayed this difficulty to my friend Cate (Mahoney, brilliant scholar), she showed me the Rilke poem from which I quote, “Geh bis an Deiner Sehnsucht Rand” (as translated by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows in their book Rilke's Book of Hours: Love Poems to God). “No feeling is final” became a mantra—or, fine, cheerleading statement—that I could return to in my lowest moments, a promise that however bad I might feel, it wouldn’t be forever.

In my poem, of course, it gets reversed: the flip side of Rilke’s statement is that any good feeling must pass, too. The profound solace I have sought in his words is tempered, for example, by the knowledge that Rilke derived his own solace from faith in a god in which I do not believe. Likewise, while DBT quite literally saved my life, I don’t always find its view of the world adequate to the world’s complexity. Its emphasis on radical acceptance—that everything is as it should be—is meant to ground the emotionally dysregulated mind back in the causal nature of reality, not to describe an ideal set of conditions, but it nevertheless doesn’t offer much in the way of how to bring about those ideal conditions. Then, the dialectic to which Dialectical Behavioral Therapy refers is between acceptance and change. I read the last line here not as a resignation, but as a reminder of my responsibility in the hierarchy of my woes.