In Their Own Words

Jenny Xie on “Melancholia”

Melancholia

The black dog approaches?

I pry open the crooked jaw.

Inside?

A heady odor, elemental.

And then?

I spin through my life again.

How so?

Slow and fast, fast and slow.

What follows?

Time, the oil of it.

What direction?

Solitude throws me off the scent.

And what lies ahead?

Even the future recoils, long as it is.

What points the finger?

All of my eye's mistakes.

And what were they?

Level.

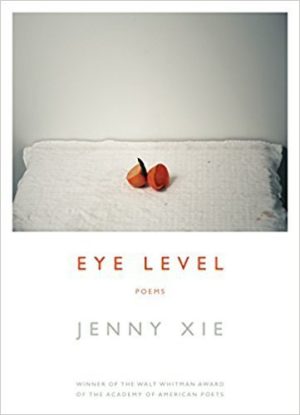

From Eye Level (Graywolf Press, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Melancholia"

In "Mourning and Melancholia" (1917), Freud traces the distinction between the psychological state of mourning, a normal response to loss that is finite, and melancholia, a pathological mourning whose labor is endless. Whereas in mourning, the object of loss is clear and can be released by the mourner with time, in melancholia, what has been lost can remain hidden and becomes internalized—"devoured" by the ego, as Freud writes. The ego absorbs the lost object and feeds on it interminably. No doubt this understanding of melancholia gets highly romanticized, but I was compelled by it, and how it suggests a fertile relationship to loss. There was something, too, about the voracious pull of appetite in the act of devouring loss that struck me.

I was energized by thinking about the ambivalence buried in melancholia, but initial attempts to write into it felt unsatisfying. The kinds of lines and stanzas I'd been employing previously didn't have enough torque to them. I was leafing through a collection of translations one evening and stumbled on a poem titled "Came to me—" by the Persian poet Rudaki (translated into English by Basil Bunting). The poem took the form of an alternating exchange of question and response between unidentified interlocutors. This formal structure, the mode of interrogation, had a certain charge. You can hear the echoes of an analysis session in it, but I was also drawn to the dance of riddling there, too.

In riddling, the slant ways of describing or approaching an object seem more pleasurable than arriving at an answer. What animates the exchange is the deferral of understanding, with descriptive lines revealing but also further obscuring the object. The back-and-forth, and the feeling around the shaded contours of something, felt like the right form for a poem aiming to locate the nature of a loss, which remains concealed and unknowable. I liked the drawing out of tension, the probing. The questions open to answers, which keep opening.