In Their Own Words

Tiana Clark on “Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #2”

Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #2

Tell me about your baptism she asked.

˜

I rose out of the water, a caught fish—slippery,

gaping for breath, brand new with righteousness.

I walked down to the frothing whirlpool,

Pastor Lonnie—a white man in a white robe,

extended his hands and helped me down the steps.

The congregation watched as I answered his questions:

Yes. Yes. Yes. Jacuzzi-warm water gurgled and spun

as his white robe spread around my little circumference,

holy creamer. He put his hand on my nose, pinched

my breath. I did not close my eyes as he buried me

under the water—under the water I heard muffled

shouting, under the water I saw Pastor Lonnie's face

ripple in thirds. He tipped my body back, lifted me up

and out from the wet coffin to the defeaning resound

of clapping and yelling from the church. My hair back

to curls, my face like the face of my birth when I was cut

from my mother—terrified, ready to scream.

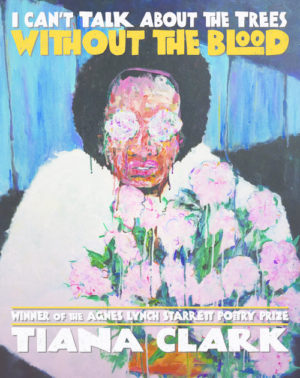

From I Can't Talk About the Trees without the Blood (Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Pray Write Me Soon: On "Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #2"

Terrance Hayes begins his latest poetry collection, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin:

The black poet would love to say his century began

With Hughes or, God forbid, Wheatley, but actually

It began with all the poetry weirdos & worriers, warriors,

Poetry whiners & winos falling from ship bows, sunset

Bridges & windows.

Rude! Just kidding. I adore this collection of sonnets, but I've never felt so seen and undressed and implicated by a poem before in my life. In graduate school, I had to trace my literary ancestry, and of course, I started with Phillis Wheatley. She was the first back female poet, and that firstness mattered to me. Though, after reading Hayes' poem, I revisited my Phillis Wheatley poems. Why did I desire to communicate with her? What about her life unlocked something in mine? Obsidian cypher? Was it an instinct based by an easy association, or was I trying to grasp at something fresh, maybe not about Wheatley, but a revelation about my own life, something I couldn't say or pinpoint without her presence percolating the watery heat inside a specific poem?

I'm still wading through the thick rejoinders, but I think I was partially trying to grasp at some notion of adynaton. I was first introduced to this word during a brilliant lecture by Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon at the Frost Place Poetry seminar several summers ago.

Adynaton, a figure of speech in the form of hyperbole taken to such extreme lengths as to insinuate a complete impossibility. The word derives from the Greek (adunatos), "unable, impossible" (a-, "without" + dynasthai, "to be possible or powerful").

Examples:

"When Hell freezes over"

Or, when Thomas Jefferson writes the following, in the Notes on the State of Virginia:

Misery is often the parent of the most affecting touches in poetry.—Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry. Love is the peculiar oestrum[1] of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately; but it could not produce a poet.

Ha! Adynaton.

Edward Hirsch writes in the Poet's glossary:

…adynaton was known in Latin as impossibilia. The formal principle of stringing together impossibilities, was a way of inverting the order of things, drawing attention to categories, turning the world upside down.

This is idea of "stringing together impossibilities" unspooled like a vibrating timeline when I began to trace my literary origins, starting from Wheatley and the sixteen white (Honorable, Reverend, Esquire) men who had to vouch for her first poetry collection in the preface, including John Wheatley, "her master," which glaringly scars the page.

"It's such a futuristic idea," Terrance Hayes said during his speech praising Cave Canem at the 2016 National Book Awards, "a world in which the descendants of slaves become poets." June Jordan argues for this literary survival in her phenomenal essay, "The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America: Something like a sonnet for Phillis Wheatley." Jordan writes:

But the miracle of Black poetry in America, the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America, is that we have been rejected and we are frequently dismissed as "political" or "topical" or "sloganeering" and "crude" and 'insignificant" because, like Phillis Wheatley, we have persisted for freedom…This is the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America: that we persist, published or not, and loved or unloved: we persist.

The difficult miracle, Black persistence itself, is a tenacious ontological resolve, built and bred from struggle and resistance and transcendence: yes, adynaton.

The Conversation with Phillis Wheatley poems were born out of this desperate need for belonging and survival, this wish to write to Wheatley inside the container of a poem, an epistolary ache. I wanted to pretend that she didn't die alone and cold and sick with her second manuscript unpublished and lost forever. I wanted to pretend that that still won't be a possibility for me or for other black women writers like me on the brink of burnout, free but struggling to survive.

I researched her correspondence with Obour Tanner, Wheatley's only known correspondent of African descent. Wheatley's letters are all that survived their seven-year correspondence (approximately 1771/72-1778), which most of the letters can be viewed at the Massachusetts Historical Society online archive. I was also inspired by Katherine Clay Bassard's article, "The Daughters' Arrival: The Earliest Black Women's Writing Community." Bassard writes:

Not only do these seven surviving letters force a necessary revision of the notion of a Phillis Wheatley completely isolated from other black women in community, but they also serve as a paradigm for the problematics and possibilities of early black women's writing community. As a broken, one-sided narrative in which letters are often sent back, delayed, or not received, large gaps in time-sometimes as much as four years-mark the desire for response with an ever- present deferral. Hand delivered by a third party (usually male), they are prone to violation and interception.' Perhaps more importantly, each letter is sent "favd by" someone, and "in care of" which marks the problematics of ownership for black women slaves, a qualification which framed even their most intimate attempts to communicate with each other.

This desire for a black women's writing community is vital for me, so crucial that I've been driven to imagine it, to dialogue with Wheatley, especially about religion, which foregrounds "Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #2," where the speaker is responding to Wheatley's imperative: "Tell me about your baptism…." I wanted to use threatening diction and a tense scene with a white paternalistic pastor figure "saving" the speaker through a religious rite. Baptism is often thought to be a joyous occasion—a rebirth—but the actual language describing the ceremony is terrifying, especially when you are a child thinking about being buried with Christ in a wet grave. There is a kind of doublespeak present in the poem that is talking back to Wheatley through the ironic use of biblical imagery. This irony is famously evident when Wheatley deftly tackles the saving grace of slaves in her often-quoted poem, "On Being Brought from Africa to America," where she writes, "Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train."

Remember! Remember she never had a black audience, so the address here is to white Christians. Remember, I'll be riding that heavenly train with you too, boo (my paraphrase). Remember, adynaton, all these impossible circumstances: a sickly child slave named after her slave ship, John and Susanna Wheatley losing a child recently before buying little Phillis—so a tenderness is there, teaching her Alexander Pope and Jesus, strung together for my survival.

I often feel impossible in my body, when I walk on the street, clutching my breath, thinking of Nia Wilson, and I'll be clutching my breath when you read this. I come from a long line of breath-clutchers, single black mothers that have prayed for my possible-ness on their knees, thick with ash and hard work. Adynation. The extreme hyperbole of black persistence and poetry, which is the ultimate organization of our collective held and spent breath[2].

In the last known letter that Wheatley writes to Obour Tanner, she says, "I hope our correspondence will revive—and revive in better times—pray write me soon, for I long to hear from you." I am responding to that urgent plea in my poems. I am trying to answer that longing by suspending time. A poem can attempt to answer a series of unanswerable griefs in verse. A poet can begin and end with Wheatley and the winos and whiners too. A poem can be a letter, or a "pyschogram" as Robert Hayden called his poem, "A Letter from Phyllis Wheatley," a dramatic monologue, which is me, saying on repeat: I begin with Phillis Wheatley. I begin with Phillis Wheatley. I begin with Phillis Wheatley reaching for coal. [3]

[1] Note the problematic use of oestrum here, meaning: period of sexual readiness, a regularly occurring period of sexual receptivity in most female mammals, except humans, during which ovulation occurs and copulation can take place; heat.

[2] This idea of poetry being the "organization of breath," was told to me by the amazing poet, Mallory Imler Powell, which she heard from another incredible poet, M'Bilia Meekers.

[3] Excerpt from my poem, "My Therapist Wants to Know about My Relationship to Work," published in POETRY.