New American Poets

New American Poets: Jennifer Chang

Pastoral

Something in the field is

working away. Root-noise.

Twig-noise. Plant

of weak chlorophyll, no

name for it. Something

in the field has mastered

distance by living too close

to fences. Yellow fruit, has it

pit or seeds? Stalk of wither. Grass-

noise fighting weed-noise. Dirt

and chant. Something in the

field. Coreopsis. I did not mean

to say that. Yellow petal, has it

wither-gift? Has it gorgeous

rash? Leaf-loss and worried

sprout, its bursting art. Some-

thing in the. Field fallowed and

cicada. I did not mean to

say. Has it roar and bloom?

Has it road and follow? A thistle

prick, fraught burrs, such

easy attachment. Stem-

and stamen-noise. Can I lime-

flower? Can I chamomile?

Something in the field cannot.

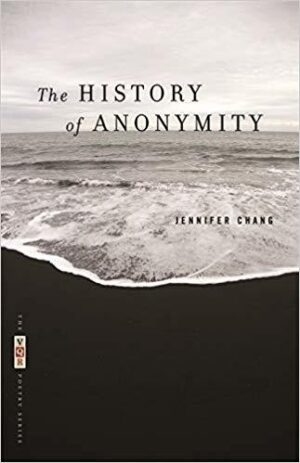

From The History of Anonymity (University of Georgia Press, 2008). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All Rights Reserved.

I write poems at my desk. I don't write every day, but I wish I did. The first draft usually begins with "I," and then I try to revise as much "I" out as possible. Lately, I prefer to write about "you."

I saw a body of water in the fog. I was on the train. I was not on my way to you, but the next day I would be, so the long route down the coast felt like the long route to you.

I wondered if the fog made the water or if the water rose into the fog. The train was fast and I thought that what I saw could also be two ghosts passing through each other. Two clouds collapsing into each other. Two anxieties panicking against each other. I became very concerned about what two things were doing what to each other and how. It was, I realized, less a problem of observation than directionality. Where was the fog going in relation to where I was going? And does water travel, enclosed as it is by land?

This led to more questions. If I walked this route, could I find my way to you? How many hours would I walk? How many days? I wondered: how long could you and I walk each night? Could you walk beyond the exertion of your body, in which case, would you not know when to stop walking? Would you ignore your destination for the pleasure of traveling? Would I, too, relinquish my body to motion? Would we permit it?

After the body of water (it may have been a lake; it may have been a river—it was not an ocean; it may have been the abundant product of recent rain) I saw fields. Pale fields of rust and yellow. Fields of tall, tired grass. Horsetail. Wheat. It was late November. I saw telephone poles in perpetuity. I saw through the window's dust and dirt, the dull filth of too much travel. I saw sad towns aspiring to be sad cities. I saw the copper dome of a church gone green at the center of one of these towns. I saw white smoke emerge from monolithic chimneys, unattached to any edifice, and collude with the fog. I saw squat rows of row houses. I questioned the empty streets of this city, until I saw that most of the houses were empty, their window frames windowless and gaping to reveal hollow interiors.

I would see you the next day. I was not traveling long or far enough to write you a letter. I was sitting very still because I wanted to see more clearly. I wanted to show you everything, so I had to remember what I saw. Dear_____, I wanted to begin--at what point does the distance between this word and where you read it become traversable? A word is not a body, but when does this stop being true? If I wrote your name like this or like that, then would you be sitting before me and not these impatient strokes on the page? When does questioning meet the audacity of an answer? When?

Dear ______, I am writing you because I have not yet arrived.