New American Poets

New American Poets: Natalie Diaz

No More Cake Here

When my brother died

I worried there wasn't enough time

to deliver the one hundred invitations

I'd scribbled while on the phone with the mortuary:

Because of the short notice no need to RSVP

Unfortunately the firemen couldn't come,

(I had hoped they'd give free rides on the truck).

They did agree to drive by the house once

with the lights on— It was a party after all.

I put Mom and Dad in charge of balloons,

let them blow as many years of my brother's name,

jails, twenty-dollar bills, midnight phone calls,

fistfights and ER visits as they could let go of.

The scarlet balloons zigzagged along the ceiling

like they'd been filled with helium. Mom blew up

so many that she fell asleep. She slept for ten years—

she missed the whole party.

My brothers and sisters were giddy, shredding

his stained t-shirts and raggedy pants, throwing them up

into the air like confetti.

When the clowns came in a few balloons slipped out

the front door. They seemed to know where

they were going and shrank to a fistful of red grins

at the end of our cul-de-sac. The clowns played toy bugles

until the air was scented with rotten raspberries.

They pulled scarves from Mom's ear—she slept through it.

I baked my brother's favorite cake (chocolate, white

frosting).

When I counted there were ninety-nine of us in the kitchen.

Everyone stuck their fingers in the mixing bowl.

A few stray dogs came to the window.

I heard their stomachs and mouths growling

over the mariachi band playing in the bathroom.

(There was no room in the hallway because of the magician.)

The mariachis complained about the bathtub acoustics.

I told the dogs No more cake here and shut the window.

The fire truck came by with the sirens on. The dogs ran away.

I sliced the cake into ninety-nine pieces.

I wrapped all the electronic equipment in the house,

taped pink bows and glittery ribbons to them—

remote controls, the Polaroid, stereo, shop-vac,

even the motor to Dad's work truck—all the things

my brother had taken apart and put back together

doing his crystal meth tricks—he'd always been

a magician of sorts.

Two mutants came to the door.

One looked almost-human. They wanted

to know if my brother had willed them the pots

and pans and spoons stacked in his basement bedroom.

They said they missed my brother's cooking and did we

have any cake. No more cake here I told them.

Well what's in the piñata they asked. I told them

God was and they ran into the desert, barefoot.

I gave Dad his slice and put Mom's in the freezer.

I brought up the pots and pans and spoons

(really, my brother was a horrible cook), banged them

together like a New Year's Day celebration.

My brother finally showed up asking why

he hadn't been invited and who baked the cake.

He told me I shouldn't smile, that this whole party was shit

because I'd imagined it all. The worst part he said was

he was still alive. The worst part he said was

he wasn't even dead. I think he's right, but maybe

the worst part is that I'm still imagining the party, maybe

the worst part is that I can still taste the cake.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Natalie Diaz

Adrian Matejka

It's tempting to get caught up in the biographical elements of Natalie Diaz's writing. The poems, as well as her author bio and interviews, invite the reader to draw direct connections between her varied identities—Mojave, a former pro-basketball player, an MFA-holder, and an archivist of Indigenous languages—and those of the speaker in her first collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec. Diaz has done so many different kinds of things that her stories have stories, but what she does on the page is much more dexterous and surprising than confessionalism or any of its variant offshoots. When My Brother Was an Aztec is a spacious, sophisticated collection, one that puts in work addressing the author's divergent experiences—whether it be family, skin politics, hoops, code switching, or government commodities.

The source material is unquestionably valuable and necessary, but what helps make Diaz's work unique is the language itself. She is a capacious linguist, one who is adept at allusion, metaphor, form, and narrative. She takes her experiences, distills them into English, Mojave, or Spanish, then twists the resultant moment with wit and grace. In Diaz's hands, the narratives are not beholden to the original experience. Rather, the experience becomes a new machine for myth, one that is simultaneous specific to Indigenous cultures and universally American. As her speaker in "Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation" puts it: "You better hope you never see angels on the rez. If you do, they'll be marching you off to / Zion or Oklahoma, or some other hell they've mapped out for us."

Which is to say Diaz both embraces and subverts mythology in whatever form it shows up—Indigenous, Western, counterculture, it doesn't matter. In her work, myth is simultaneously reified and undercut because it has to be. Myth is only "myth" insofar as it approximates the human condition. Joseph Campbell once said all myths address "transformation of consciousness," and we find these transformations everywhere in Diaz's work. In her poems, love becomes "a pound of sticky raisins / packed tight in black and white / government boxes" while a meth-addicted brother is "Borges's Bestiary. / He is a zoo of imaginary beings."

At its center, this collection is about the transformation of traditions—the traditions of poverty, the traditions of Indigenousness, the traditions of poetics. It takes a poet of rare skill and clarity to write a triolet that includes assault arrests, Sisyphus, meth and Lionel Richie. And it is in these moments where Diaz so elegantly negotiates experience, tradition, and myth that show us the range of her skill as a writer. She is a poet who understands tradition but is not beholden to it. She is a poet who will help us write into the future as she excavates the past and interrogates the present. She finds beauty and worth in the zoo of drug addiction and the gut-busting weight of government raisins, and her experiential insights make us wiser, more self-aware, and, in the end, more human.

Statement

Natalie Diaz

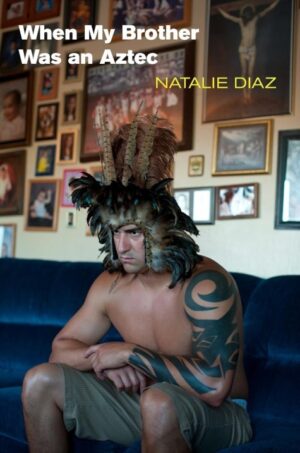

When I received the two advance copies of my first poetry book, When My Brother Was an Aztec, I kept one and gave the second copy to my brother Mino—he is the tattooed brother who posed for the photo on the book's cover. That night, unbeknownst to me, my mother, my father, and five of my eight siblings gathered in Mino's living room taking turns reading from the book. They didn't read out loud. Instead, they read quietly, flipping to poems at random. Sometime after midnight, I received a rain of text messages with comments or questions from my siblings. One of those text was from my youngest brother. It said: What do u mean? Did u mean u want Richie to die? That's fukd up. He was referring to a poem in the book called "No More Cake Here," in which I imagine the events that might take place after a phone call announcing the death of my meth-wrecked oldest brother. It was a poem that surprised even me when I wrote it. It uncovered a truth in me that I almost wished I didn't know existed: the late-night-early-morning phone calls that we all dread because they usually bring some form of bad news about my brother might one day bring us/me a type of relief or at least an ease of sorts, because one day that phone call might announce that my brother is free of his worst self, meaning we/I would be free from this version of him as well, meaning he would be dead.

The next morning, my mother and my youngest sister, Franki, dropped by my house unexpectedly. I knew my mother was bothered as soon as she walked in the door.

Go ahead, Mom, tell me, I said.

Tell you what? she replied.

I can tell you're bothered, so you might as well just say what's in you, I continued.

Well, it's just that the things you wrote…it didn't happen like that, she told me. That's not the way it was.

Before I could respond, Franki blurted out, What do you mean, Mom? That's exactly how it happened.

Of course, my Mom and Franki were both right, and they were both wrong—it was all true; none of it was true. And just as Val was right when he said what I wrote about my brother was fukd up, he was also wrong by thinking I shouldn't have acknowledged the truth in me that led to that horrible poem.

The greatest and perhaps single piece of knowledge I carry in me when I write is that there are multitudes of truths contained in a single story. I learned this not by any academic lesson, but within my family. I grew up in the Arizona/California desert, on the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation, which everyone called the Indian Village, with four brothers and four sisters in a two-bedroom house, to a native mother and a Spanish, Catholic father. We held to many truths all at once. Each seemed to strengthen the possibility of the other, rather than cancel it out. In my house, we never had to choose between the numerous parts of ourselves—we were all of those things, at the same time, sometimes in a noisy collision, sometimes in an easy weave.

When I write, I bring all of my truths, even the Judas-truths that make me feel like the betrayer whose dirty hands are resting on the table for everyone to see, including God. For me, writing is less a declaration of those truths than it is my interrogation of them. Uncovering the darkness in me that led to some of the poems about my brother also lights up the hard, bright way in which I love him and the small wars I wage to win him back. The monsters and hoofermen I choose to look in the eyes and teeth when considering my rez and this country's history are also the truths that have built in me a strength and compassion that help me to survive this world. Truth is that little animal we chase and chase until we suddenly glance over our shoulder and realize it has been chasing us all along.