New American Poets

New American Poets: Oliver Bendorf

Queer Facts About Vegetables

In 1893, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the tomato is a vegetable (for taxation purposes), even though botanically it fit the definition of a fruit.

I know I am a nightshade,

it says to its own limp vine.

I know how to burst

against teeth

with my juice and seed.

I'm as small

as a thumbnail, no,

I'm as big as the harvest

fucking sun.

I'm fresh blood

on a small curled fist.

I can be a boy, I know,

but never a man.

I can be Sunday gravy

or a pickled green.

This is still the tomato

talking to the vine,

as told to me.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Oliver Bendorf

Natalie Diaz

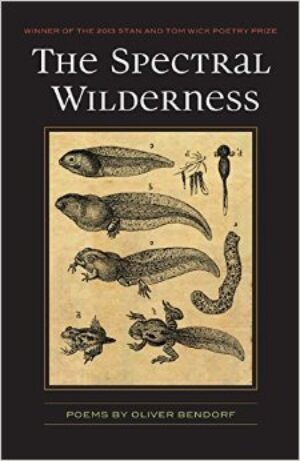

One of the more violent and beautiful transformations of body we recognize is that of the moth or butterfly, a change that takes place in the privacy of a cocoon. The cover of Oliver Bendorf's first book, The Spectral Wilderness, promises a transformation equally violent and beautiful—a tadpole into a frog—the transformation of one body into a new body that has been inside it all along, a transitioning of gender. This poet takes an incredible risk: rather than hide the transition and reveal the speaker only after he has emerged beautiful, Bendorf makes the transformation public. The wilderness he renders emotionally and imagistically is partly typical—an unexplained, unexpected landscape marked by solitude and loneliness—yet he crafts this new wilderness in such a way that we readers are implicated as witnesses and companions: "They said there would be spiders, / & there are—cobwebs appear / in my home like apparitions, / ghosts of a heaven they said / there would be. And I have found / good people here & even / fewer ways to feel alone, /…

It is with the hands that we first enter his spectral wilderness, just as into any dark we go hands-first, to find what the rest of us will run into. Hands are one of several images that recur like specters signaling the expectation of change as well as the fear of what that change will mean. In "I Promised Her My Hands Wouldn't Get Any Larger," the beloved traces the speaker's hands each morning, and they hang the sheets of paper along the wall: "When I / study them, they look back at me like busted / headlights." In poem after poem he builds and rebuilds a body, a story, a desire that are at once familiar and strange, capable of brightness like any headlight but also capable of losing that light in their brokenness which makes us love them even more.

Love is not spared transformation, no matter how achingly the speaker wants to protect it. The beloved in "Blue Boy" begins to cry and pleads, "don't turn into a man. If you must turn into something, turn into a wolf." Suddenly we are unsure of how much change this love, any love, will endure, just as we are unsure of how much love this change will allow to remain in its wake. We grieve along with the speaker, but not the kind of grief that stops us, rather it is a grief that helps us mark the pain so that we can finally move—grief, after all, is not the same thing as regret. And so many of these poems are love letters to the solitude of these losses and transitions, but they too are love letters to what could be waiting for the speaker at the end of this transformation.

In "Take Care," which closes the book, he leaves us wrestling with our own changes, the ones we want to believe are growth rather than grief, the ones that let us feel more present in our selves instead of as if we've left our selves behind: "I mistake my hands for belief all the time. / I keep waking up expecting them to be / someone else's, but so far they're only / mine…" Bendorf's poems give us all we have ever wanted, to wake up and feel that the body we are in is ours, that the hands on the ends of our wrists—our body's gates of tenderness—are large enough to hold in them all the things we have desired.

Statement

Oliver Bendorf

The words gender and genre, they share a root in genus, a kind, a sort, a type. Find me in the slippages between them. This is my poetics: "pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and for responsibility in their construction."[1]

***

I write in order to prepare myself for what nothing else prepared me for: the love and loss of transformation, which is to say, the story of being a body. I wanted to explore how love and loss make a boy, and how a boy makes a man. And if my book is a sad book, I guess I believed that there is always some sadness to becoming a man, whether you were born a boy or a girl.

***

I get stuck in the spaces between wanting to universalize my experience of becoming a man—I do see similarities in many kinds of bodily betrayals and makings and transformations—and sensing that there is some specificity to the transgender experience, which is somehow more than a sum of its nonspecific parts. I want to take others with me / I want to go alone / I am going alone / come with me / meet me there. John Muir wrote in a letter to his wife in 1888, "Only by going alone in silence, without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness." Is that true? Is it only by going alone? But you are here, and you, and you, and you.

***

When I first started writing the poems that would become The Spectral Wilderness, I wasn't yet called Oliver. Going by a new name doesn't happen in one second; it's more like a fading out and in. There's an overlap. I used to wake up in my apartment in DC and have a panicky feeling of not knowing what to call myself. Sort of like that hotel feeling, before you remember what town you're in, but far more disorienting, to be nameless, and not as quickly resolved.

***

I told Natalie (Diaz) recently that my poems transitioned before me. Like I sent them ahead to try to find out what I would encounter in this wilderness of becoming. What is the size and shape of this wilderness? I don't know; I can't help but think of the book apart from what it isn't: poems cut from the manuscript, poems I didn't even write, other books it might have been, other bodies, other names, they come back to me in picture-dreams like mostly-friendly ghosts. There are images and then there are afterimages. The book goes boo. I write to try to stay on good terms with these hauntings and their desires. What does the body want?

***

Moving between kinds, losing something, returning for it. That's my next book, the returning. What happens when the boy-man returns for the girl he used to be? What kind of language will they negotiate for the body they now share?

[1] From "A Cyborg Manifesto" by Donna Haraway