New American Poets

New American Poets: Reginald Dwayne Betts

Prison

Prison the sinner's bouquet, house of shredded & torn

Dear John letters, upended grave of names, moon

Black kiss of a pistol's flat side, time blueborn

& threaded into a curse, Lazarus of hustlers, the picayune

Spinning into beatdowns; breath of a thief stilled

By fluorescent lights, a system of 40 blocks,

& empty vials, a hand full of purple cranesbills,

Memories of crates suspended from stairs, tied in knots

Around street lamps, the hours of unending push-ups,

Wheelbarrels & walking 20s, the daughters

Chasing their father's shadows, sons that upset

The wind with their secrets, the paraphrase of fractured,

Scarred wings flying through smoke, each wild hour

Of lockdown, hunger time, & the blackened flower.

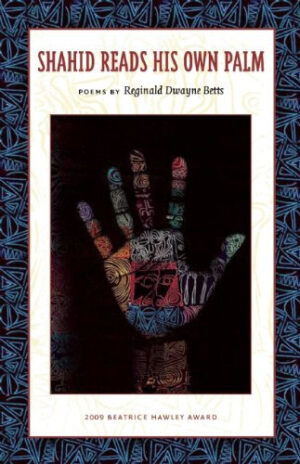

From the book Shahid Reads His Own Palm published by Alice James Books. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Reginald Dwayne Betts

Jericho Brown

As a poet, R. Dwayne Betts can be counted on for three things:

1. He is not bound up in the outlawing of subject matter. I don't know where he got the idea that his poems would be made of all his imagination and experience has to offer him every time he goes to the page. I certainly wish I knew this was an option for writing much earlier in my career. Dwayne means to take the elements of his entirety and juxtapose them until they make music. That makes me happy, even when the poems are what non-readers call "really sad." How lovely it must be for a poet to believe he has a self to hone into art rather than a self to create! Interesting, this fearlessness.

2. He is a man of metaphors. He isn't foolish enough to think he knows what anything is, so he's content with the joy of pinning his subjects down as many ways as possible, with allowing what ever he observes its own transformative life. Like Whitman, he is obsessed with litanies. Like Ali, he concerns himself with ghazals. He is married to the beginnings of things, and because he's faithful, the things never end.

3. Betts will always be a poet of potential. His worst poems are his best ones, for even in these, he reaches toward the answers to questions that will never be answered honestly in a critic's essay or a statistician's report. He loves to incriminate his own existence and the world in which he participates. Therefore, he will always have work to do, and he will never be satisfied with how well he does it. In his best work, he taps into this potential and immediately sets a higher goal.

Statement

Reginald Dwayne Betts

I contradict myself. Often. Sometimes on purpose. There are gray areas for poems that don't run from nuance and embrace neverminds; I am after those spaces. These spaces are close to the belly, the center of where the hurt and the pain brim. And where pleasure blooms. I think of Etheridge Knight's "Belly Song" and how he writes, "when she opened to me/ like a flower/ but I fell on her/ like a stone." I want not to be afraid to know I've been a stone. To write poetry that admits and confronts that, in myself, in the world – and in doing so, helps make space for more petunias (such a nice sounding word, petunias). Let me put it this way, I am a poet and remember James Brown singing "a man got to go back to the crossroads before he finds himself." The belly is the only vibrant thing at the crossroads. As a writer I go there, and try to listen, try to look.

Or let me say this: In public I understand that me speaking includes my hands waving, includes bursts of laughter, includes me staring off into space while getting lost in a memory. I am certain a poem should be able to do this, should be able to approximate the range of who I am and what I imagine the world to be, with words. A poem should be able to maneuver through an emotional, physical, imagined landscape in the same manner that we maneuver. It should also be able to fail as we fail, and still in that failing say something lovely.

My biggest influence was the guy who slid Dudley Randall's The Black Poets under my cell door in solitary, then a close second would be Etheridge Knight's "Feeling Fucked Up," Nas' "It Ain't Hard To Tell," Isaiah Thomas's sixteen points-in-two-minutes-outburst, and a drawing I watched an eighteen year old kid do in the county jail. All of which is to say these things expanded and shaped my ideas of style. MCs taught me to be excited by dope lines. Hearing Nas in "It Ain't Hard To Tell" spit: "speak with criminal slang: begin like a violin, end like Leviathan," was a lecture on simile. MCs taught me juxtaposition and allusion, they taught me advocacy and the power of narrative. They also make me realize that if a rhyme can be a thing all unto itself, so, too, can poems. And they prepared me for Robert Hayden, for Shakespeare.

I want a poetics hurting to communicate, a poetics that builds bridges over chasms created when folks would have us believe our differences ruin us. I remind myself, always, to write with a harmonica player's verve. Think of it, the harp player bends notes to get at a sound the audience will recognize. So much instinct, creating a howl from the belly. Listen to Sonny Boy Williamson, to Little Walter. Their harps moan like I want my poems to moan. All emotion. All intellect. This is what the audience wants, I believe – a song that threatens to tear you apart each time it's sung. And the most important thing, always, always, is the now that it all, the poem's voodoo, the harp's funk, the MCs braveness, resonates in.